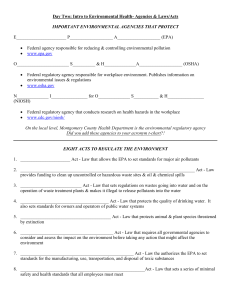

E-GOVERNMENT AND REGULATION: THE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR’S WEB-BASED COMPLIANCE ASSISTANCE RESOURCES

advertisement