DCAF Measuring the Impact of Peacebuilding Interventions Vincenza Scherrer

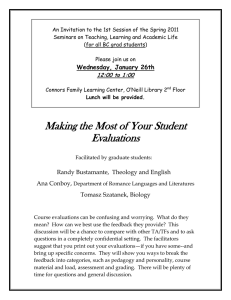

advertisement