W WH HA AT

advertisement

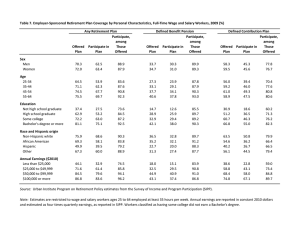

S T R A I G H T T A L K on Social Security and Retirement Polic y URBAN INSTITUTE No. 25 WHAT HAPPENS TO REPLACEMENT RATES OVER THE COURSE OF RETIREMENT? Eugene Steuerle and Christopher Spiro REPLACEMENT RATES, WHICH COMPARE INDIVIDUALS’ initial Social Security benefits with previous wages, are often used to determine whether or not recent retirees can maintain their preretirement standard of living. Replacement rates, however, can be unsteady measures. As discussed in a previous brief, they look different depending on the wage (for example, average, highest, or most recent) with which a new Social Security benefit is compared.1 But such rates can also appear different over the course of retirement. Analysts typically rely on a replacement rate determined at the specific moment of retirement. Because initial Social Security benefits are based on wageindexed earnings, the replacement rate relates the retiree’s wages to those of the general population. If society has grown richer, the benefit reflects this. However, analysts seldom attempt to measure this type of relative replacement rate at any point during retirement. Relative replacement rates change during retirement because after the Social Security benefit is established, it grows at the slower pace of prices and only its real, not relative, value is maintained. Social Security benefits do not grow along with average wages in the economy and, therefore, rela- 1. See Straight Talk No. 24, May 30, 2000. T H E R E T I R E M ● June 15, 2000 tive replacement rates (which compare the benefit with this wage) during retirement appear to drop dramatically. Figure 1 displays the earnings pattern of an average-income worker, based on actual earnings records. This worker’s initial benefit of $9,728 at age 65 steadily erodes relative to average wages in the economy. By the time this worker turns 85, his benefit has fallen from 31 percent of the average wage of all workers to 25 percent of the average wage of all workers.2 By the time this worker turns 85, this erosion has reduced his replacement rate from 52 percent of his average wage to 43 percent. Unfortunately, this erosion of retirees’ relative living standards occurs just as their needs are increasing. Younger retirees tend to be better off than older retirees—they are more likely to be healthy, earning additional income, and receiving help from a spouse. Despite their generally stronger standing vis-à-vis older retirees, younger retirees receive greater Social Security benefits than their older counterparts: Each subsequent generation tends to earn more than the previous one and is therefore entitled to higher benefits. Thus, at any point in time, Social Security benefits are actually inversely related to the needs of the various age groups who receive them. This contradicts Social Security’s primary goal of protecting against the vulnerability that can accompany aging. While price-indexed benefits allow retirees to maintain their purchasing power over time, they do not accommodate increased demand for goods and services. Retirees are therefore unable to increase their consumption as the economy grows. They may also become less able to purchase necessary services (such as those provided by a nurse or other caretaker) whose prices increase according to wage, not price, growth. Because wages grow faster than prices, the cost of these services outpaces a retiree’s ability to pay for them. 2. This particular method of calculating the average wage includes years in which workers receive zero earnings, but this has no effect on the general issue that Social Security income falls over time relative to average wages. E N T P R O J E C T S T R A I G H T T A L K on Social Security and Retirement Polic y Private pensions can exacerbate declines in relative replacement rates. While private pensions are an important source of income for many retirees, they rarely index benefits for price growth—and almost never for wage growth. Hence, pension benefit payments decline in real value during retirement years. Thus, combining private pension with Social Security income further reduces replacement rates. While Social Security tries to maintain relative standards of living at the moment of retirement, a similar attempt is not made after retirement. The reduction in relative replacement rates during retirement reflects this. As retirees age, they become isolated from the fruits of economic expansion. The paradoxical result is a Social Security (and private pension) system that pays greater benefits to age groups who need them less and smaller benefits to those who need them more. Eugene Steuerle is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, where his research includes work on Social Security reform. Christopher Spiro is a research assistant at the Urban Institute. Note: The Straight Talk series is on vacation. The next Straight Talk will be released July 15, 2000. This series is made possible by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant. For more information, call Public Affairs: 202-261-5709. For additional copies of this publication, call 202-261-5687 or visit the Retirement Project’s Web site: http://www.urban.org/retirement. Copyright ©2000. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Urban Institute, its sponsors, or its trustees. Permission is granted for reproduction of this document, with attribution to the Urban Institute. FIGURE 1. Relative Replacement Rates Fall during Retirement* $25,000 ACTUAL LIFETIME EARNINGS PATTERN OF AVERAGE EARNER AVERAGE EARNINGS OF AVERAGE EARNER Wage-Indexed Dollars $20,000 $15,000 $10,000 BENEFIT OF AVERAGE EARNER $5,000 $0 22 25 30 40 35 50 45 55 Age 60 65 70 75 80 85 *For worker born in 1935 and retiring at age 65 in 2000. Source: Eugene Steuerle and Christopher Spiro, The Urban Institute, 2000. T H E R E T I R E M E N T P R O J E C T