L LO OO OK

advertisement

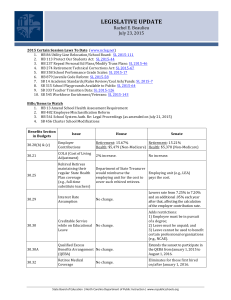

S T R A I G H T T A L K on Social Security and Retirement Polic y URBAN INSTITUTE No. 27 July 30, 2000 ● LOOKING AT SOCIAL SECURITY REFORM THROUGH A SOCIOECONOMIC LENS High-Income Retirees Eugene Steuerle and Christopher Spiro IT’S USEFUL TO FLIP EVALUATIONS OF SOCIAL Security reform on their head: Instead of scrutinizing reforms and generalizing about their impact on retirees, we scrutinize retirees and generalize about reforms. Many policymakers spell out the details of their reform proposals but, when describing how those proposals will affect lives, do not distinguish between groups of retirees. In reality, groups of retirees will experience reform differently and will take on a degree of burden for reform consistent with their socioeconomic status. Most reforms share a basic premise. They attempt to save money and, at the same time, maintain the safety net for the most needy. So, regardless of the specifics, any reform that becomes law will probably do both of these things. By assuming these common traits, we can focus on reform’s potential impact on different groups of retirees. This exercise gives us a better idea of the repercussions of Social Security reform for recipients, regardless of which laws are eventually passed. T H E R E T I R E M High-income individuals will almost inevitably pay for a significant share of Social Security reform. If reform cuts benefits, high-income retirees are likely to lose more than their lower-income counterparts— particularly if the poor are extended greater protections. Even if the current benefit structure is maintained, high-income retirees will bear a disproportionate responsibility for the additional taxes required to address the system’s solvency. This group would probably prefer a reform that cuts benefits to one that increases their taxes (that is, if both reforms cost the same). Benefit cuts keep richer retirees in greater control of their money, allowing them to invest it as they see fit (traditionally, this group achieves very good rates of return on their saving). Thus, for those in this group willing to save a bit more, reform will likely have little effect on retirement income. Nevertheless, there are too few highincome retirees to carry the entire burden of reform. Average-Income Retirees Unlike rich retirees, middle-class retirees are less prepared for their own retirement; unlike poor retirees, they can afford to do more to prepare. Because most retirees fall into this socioeconomic group, the success of Social Security reform rests on their willingness and ability to make adjustments in their approach to retirement. Given the eventual shortfall in Social Security revenues, it seems almost inevitable that the middle class will need to take on a larger share of the burden for its own retirement. E N T P R O J E C T S T R A I G H T T A L K on Social Security and Retirement Polic y To do this, the middle class needs to enter retirement with significantly more private assets. Currently, half of all retirees go into retirement with few assets. Three-quarters have private savings—in retirement accounts, homes, and other assets— worth less than government-promised benefits (Social Security and Medicare) from future taxpayers. The middle class may also need to extend their work lives. Today, individuals retire on average for about one-third of their adult lives. Once the baby boomers retire, close to one-third of all adults are scheduled to be Social Security beneficiaries. In effect, unless most middle-class retirees work and save more, their children will have to support them through higher taxes. responsibility for bringing Social Security back into solvency and improving its safety net. Those with limited abilities and lower incomes will be excused from much of the responsibility. One way or another, all Social Security reform proposals will have to demand more saving, work, or taxes from the middle class— a fact that politicians are often reluctant to acknowledge. The middle class is, after all, a majority of both beneficiaries and taxpayers. By first deciding how they want different groups of retirees to be affected by reform, policymakers can better craft proposals that bring about the changes they intend. Eugene Steuerle is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, where his research includes work on Social Security reform. Christopher Spiro is a research assistant at the Urban Institute. Low-Income Retirees Protecting the elderly from poverty is Social Security’s primary purpose. Poverty rates for certain groups of retirees remain high—16 percent for divorcees and 21 percent for those who have never married. Reform can easily create a stronger safety net for poor retirees and alleviate much poverty among the elderly. However, this requires a degree of sacrifice—more saving, work, or taxes—from everyone else and, therefore, may be resisted by those with higher incomes. *** In all likelihood, the burden of reform will not fall equally on all retirees. Those with high incomes will have to take on a disproportionate share of the T H E R E T I R E This series is made possible by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant. For more information, call Public Affairs: 202-261-5709. For additional copies of this publication, call 202-261-5687 or visit the Retirement Project’s Web site: http://www.urban.org/retirement. Copyright ©2000. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Urban Institute, its sponsors, or its trustees. Permission is granted for reproduction of this document, with attribution to the Urban Institute. M E N T P R O J E C T