HUMAN RIGHTS AND MILITARY OPERATIONS: CONFRONTING THE CHALLENGES WORKSHOP REPORT Noëlle Quénivet

advertisement

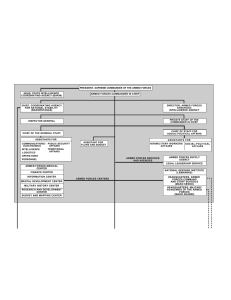

Human Rights and Military Operations HUMAN RIGHTS AND MILITARY OPERATIONS: CONFRONTING THE CHALLENGES WORKSHOP REPORT Noëlle Quénivet Aurel Sari OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 2 Human Rights and Military Operations Human Rights and Military Operations: Confronting the Challenges Noëlle Quénivet and Aurel Sari July 2015 © The Authors Picture credits: Reuters (page 3 & 8), MoD (page 10, 14 & 19), Supreme Court (page 16). About the Strategy and Security Institute The Strategy and Security Institute (SSI) is an interdisciplinary centre for research and education within the College of Social Sciences and International Studies of the University of Exeter. SSI carries out research, consultancy and teaching in the fields of global security and strategy, particularly relating to how individuals and organisations deal with conflict under intense pressure. SSI is both a response to the strategic imperative made stark in recent interventions, and an opportunity to fill the gaps these interventions have uncovered by enhancing the strategic competence of the leaders of the future. The Institute is directed by Lieutenant General (Retd) Professor Sir Paul Newton KBE and is based in Knightley on Streatham Drive. Human Rights and Military Operations Contents Executive Summary.......................................................................................................2 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................3 2. The Services v Strasbourg: The UK Armed Forces in the European Court of Human Rights ................................................................................................................5 Introduction............................................................................................................5 Overview of the Cases ............................................................................................5 Understanding the Distinction between Operations in Northern Ireland and Abroad ....................................................................................................................6 Centrality of Article 2 ECHR in Military Operations ...............................................8 Obligations under Article 2 ECHR ...........................................................................9 Pre-Deployment Obligations ..............................................................................9 Obligations during Deployment (and Derogations).........................................10 Obligations after the Operation.......................................................................11 Conclusion ........................................................................................................1213 3. Juridification of the British Armed Forces and Efforts to Fight Back: What Are the Options? ................................................................................................................14 Introduction..........................................................................................................14 Juridification Process............................................................................................14 Strategic Approaches to Addressing Juridification ..............................................17 Reversing the Juridification Process.................................................................17 Eliminating Legal Complexity and Uncertainty................................................18 Mitigating Complexity and Uncertainty...........................................................18 Proposed Solutions...............................................................................................18 Conclusion ............................................................................................................20 4. Conclusion .............................................................................................................21 About the Authors.......................................................................................................22 About the Project ........................................................................................................23 1 Human Rights and Military Operations Executive Summary The present report summarizes the proceedings of a workshop on ‘Human Rights and Military Operations: Confronting the Challenges’ held on 6 February 2015 at the University of the West of England. The proceedings confirmed that the application of international human rights law, in particular the European Convention on Human Rights, to deployed operations presents significant legal and practical challenges to the armed forces. The proceedings also confirmed, however, that confronting these challenges requires a nuanced approach, as the nature of the problem neither demands nor admits of an absolute solution. In this respect, some participants felt that the continued focus on the applicability of the European Convention might divert attention from engaging with the question of the application of its provisions in the context of deployed operations. Both 2 of these issues merit attention. The participants also considered that the question of derogations under Article 15 of the European Convention nonetheless remains relevant in this context. The participants agreed that developments in the legal framework governing overseas military operations over the last two decades, including the growing prominence of international human rights law, cannot be reversed, but only influenced. The adverse effects of these developments, in particular the increased complexity and uncertainty of the law, therefore cannot be eliminated, but only mitigated. Flexibility and adaptability are key. The workshop formed part of a research project on ‘Clearing the Fog of Law: The Impact of International Human Rights Law on the British Armed Forces’, supported by the British Academy. Human Rights and Military Operations 1. Introduction On 6 February 2015, the University of the West of England hosted a Workshop entitled ‘Human Rights and Military Operations: Confronting the Challenges’. The purpose of the workshop was to provide a forum to examine the impact of human rights law, and more particularly the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), on military operations conducted by British armed forces abroad. The workshop focussed on the challenges facing the UK in light of the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights and the interrelationship between international human rights law and international humanitarian law. The participants consisted of 15 subject matter experts. To facilitate a frank and open dialogue on the applicability and application of human rights in military operations, the workshop was subject to the Chatham House Rule. The event formed part of a research project entitled ‘Clearing the Fog of Law: The Impact of International Human Rights Law on the British Armed Forces’, supported by the British Academy. For more information about this project, see page 23 below. The workshop organisers, Dr Noëlle Quénivet (University of the West of England) and Dr Aurel Sari (University of Exeter), briefly introduced the project and its aims so as to contextualise the discussion. The morning session set out to provide an overview of the cases brought before the European Court of Human Rights involving the British armed forces and to highlight the challenges posed by the Court’s jurisprudence. The afternoon session was dedicated to examining the more general trend of juridification of military law and the possible solutions to maintain the operational freedom of the armed forces. The morning and afternoon presentations served as a jumping board for debate, allowing participants to interact at any stage. The purpose of this report is to provide a record of the current state of the law and the challenges it poses to military operations as perceived by the workshop participants. 1 As such, the report reflects the discussions which took place at the workshop and must be read in the light of the following notes of caution. The report does not aim to present a comprehensive analysis of the field, but covers only subjects which were addressed during the discussions. It provides the reader with an overview of a variety of opinions expressed during the event. Where the group came to a strong majority position or even a consensus on a particular issue, the report indicates so. However, not every participant, including the organisers, necessarily share all the views identified in The organisers would like to thank Olivia Curtis for taking notes during the discussions and thus allowing this report to be written. 1 3 Human Rights and Military Operations this report nor do these views necessarily reflect the position of any institution. Like any lively exchange of thoughts among subject matter experts, the discussions did take sharp and occasionally unexpected turns and not all the questions raised were 4 settled conclusively by the group. The report does not make a sustained effort to reconcile the views expressed by the participants where these have diverged or to provide a conclusive answer to the questions left open during the discussion. Human Rights and Military Operations 2. The Services v Strasbourg: The UK Armed Forces in the European Court of Human Rights Introduction Dr Noëlle Quénivet began by introducing 31 cases, spanning from 1978 (Ireland v UK) to 2014 (Hassan v UK), which involved members of the British armed forces and which were brought before and decided by the European Court and the European Commission of Human Rights. The primary objective of this review of the case-law was to provide a clearer overview of inter alia the types of applicants involved, the litigation grounds and the types of circumstances examined. Overview of the Cases Whilst the number of cases brought in the 1970s and 1980s was minimal, a clear increase can be identified from the 1990s onwards. One participant wondered whether a correlation with the adoption and implementation of the Human Rights Act 1998 could be established. Bearing in mind that cases were brought from the beginning of the 1990s onwards, it was difficult to draw definite conclusions. Yet, this matter needed to be examined to understand why cases pleaded in the Cases 2010 20% 2000 45% 1990 32% UK legal system were unresolved from the applicant’s perspective and thus resulted in being argued before the Court in Strasbourg. Another participant also pointed out that in this respect more attention should be paid to the adoption of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, as it would have further impact on British laws relevant to the armed forces. Remarkably, the majority of the applicants in these 31 cases were (former) members of the armed forces or their relatives. This categorisation (Ministry of Defence (MoD) personnel and relatives, non-MoD personnel and relatives) was rather helpful to distinguish between the different types of situations brought before the ECHR bodies. With regard to Ministry of Defence personnel and their relatives, all cases, with no exceptions, fell within three groups: cases involving discrimination against the service personnel on the basis of sexual orientation and their subsequent dismissal from Applicants 1970 3% 1980 0% MoD person nel 58% NonMoD 39% State 3% 5 Human Rights and Military Operations the forces (Article 8 ECHR pleaded alone or combined with Article 14 ECHR; violation of Article 8 ECHR found); cases relating to the operation of the military justice system (Articles 5 and 6 ECHR pleaded; violation of Articles 5 and 6 ECHR found); cases relating to scientific tests carried out on service personnel (Articles 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 13 and 14 ECHR pleaded; violation of Article 8 ECHR found). The pattern of the first two groups of claims was similar. A first applicant raised the issue before the Court which declared a specific rule to violate the Convention. Further claims were then initiated by applicants in a similar situation, resulting in the UK being repeatedly found in violation of the Convention for the same rule. The UK then amended the law or repealed the act in contravention of the Convention, thereby stemming the flow of cases brought before the Strasbourg bodies. This shows that the Court will continue to pronounce the UK in violation for as long as the domestic law or measure in question is not repealed or otherwise brought in conformity with the Convention. With regard to applicants unrelated to the Ministry of Defence, their grievances fell within two groups: the situation in Northern Ireland; the situation in Iraq. One participant mooted that as the number of human rights proceedings against the armed forces for acts committed in Afghanistan increases, undoubtedly a number of cases will find their way to Strasbourg in the next 6 few years, provided they were not dealt with at the national level to the satisfaction of the applicant. Understanding the Distinction between Operations in Northern Ireland and Abroad Dr Quénivet observed that whereas the armed forces seemed to be concerned about the recent cases relating to their deployment in Iraq, they seemed to be less concerned when they were facing similar claims in the context of Northern Ireland. In fact, the articles pleaded and violated before the European Court of Human Rights in relation to the situation in Northern Ireland and Iraq were rather similar, with the exception of Articles 5 and 6, which had been successfully pleaded in cases relating to Iraq, but not Northern Ireland: Northern Ireland: pleaded Articles 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 14 and 34 ECHR; violations of Articles 2, 3, 8, 13 and 34 ECHR; Iraq: pleaded Articles 2, 3, 5, 6, 13 and 34 ECHR; violations of Articles 2, 3, 5, 6, 13 and 34 ECHR. Bearing this in mind, the question arises whether there is a fundamental difference between the deployment of British troops abroad and their deployment at home, which would explain these different levels of concern? Dr Quénivet jumpstarted the debate by giving the participants two fictional stories, one inspired by a case involving an operation in Northern Ireland and another being the same case, though adapted to a fictional overseas deployment. Based on this, the partici- Human Rights and Military Operations pants identified a number of relevant differences: The extra-territorial application of human rights law and especially of the ECHR. Differences between operations in a law enforcement context and operations in armed conflict. The situation in Northern Ireland was one of internal disturbances which was more static and did not reach the threshold of an armed conflict. Thus only a human rights law “...undoubtedly a number of cases will find their way to Strasbourg in the next few years.” framework applied. In contrast, the situation in Iraq was one of an armed conflict, where the situation often quickly moved from a conduct of hostilities to a law enforcement framework and back. In the afternoon session the interrelationship between international human rights law and international humanitarian law was debated at length. Manpower. After an incident engaging Article 2 ECHR, the armed forces must effectively secure the area to collect the evidence and ensure that it is not tampered with. In an armed conflict, having a sufficient number of personnel available is at best a challenge and, in some cases, unrealistic, if not impossible. In peacetime, securing the area for investigation is much easier. Existence of an established rule of law framework. Participants noted that it was easier to abide by the procedural (including practical and investigative) aspects of Article 2 ECHR in Northern Ireland, as the armed forces relied on domestic law and were acting at home, in a context they knew well. In contrast, operating in a State such as Iraq where rule of law structures are severely weakened or absent complicates the task of the military in relation to the application of human rights law. As the law seems less clear in the latter context, members of the armed forces are more likely to do what is feasible on the best interpretation of what the unsettled legal position is. This explains why applications relating to operations in Northern Ireland for violations of Articles 5 and 6 ECHR were unsuccessful. In contrast, the UK has been found in violation of these articles in relation to the conflict in Iraq. A number of possible explanations were mentioned. First, the legal basis for detention was clearly established in the context of Northern Ireland. It was less so in relation to Iraq or Afghanistan. Moreover, until recently the legal basis for detention had not been questioned. Second, due to the evolving case-law of the European Court of Human Rights, the standards imposed under Articles 5 and 6 ECHR are now higher. Likewise, the legal framework regulating the condition of detention in Northern Ireland was well-defined whereas in Iraq and Afghanistan the concomitant application of the law of the host State complicated such 7 Human Rights and Military Operations 8 matters. Again, it was noted that until recently such issue had not been considered as problematic, in particular where there was an established interface with domestic law institutions. Multinational operations. The close collaboration with other armed forces, such as those of the US and Australia, poses certain challenges relating to the application of human rights law. Indeed, whilst the UK is bound by the ECHR, other coalition partners may not. Being bound by a different set of laws leads to some operational constraints on the part of the UK. That being said, whilst the US and the UK are adopting different methods – the US is deploying a reputational approach and the UK a legal approach – the end result, that of a minimising of casualties and damages (be they military or civilian), is the same. As a result, the two States work well in tandem. The human rights obligations of host States. The host State might not be bound by international human rights instruments or only by some. Do British forces have to comply with the local laws even if they violate the UK’s obligations under human rights law? This again raises a number of questions. Some similarities between the involvement of the armed forces in Northern Ireland and in Iraq/Afghanistan were also pointed out, such as the use of lethal force by the armed forces, their role in preventing criminal activities, the use of detention as a security measure (often for preventive purposes), the hostile/unfriendly environment in which they were conducting their operations, and the scale of their tasks and the limited nature of the resources available to carry them out. Centrality of Article 2 ECHR in Military Operations Attention was then drawn to Article 2 ECHR. The centrality of this article in relation to military operations cannot be denied. First, it must be noted that cases in which the UK was found to have breached Article 2 ECHR focused on the planning of the operation (McCann v UK) and the investigation stage, but not on the (un)lawful killing itself, ie the actions of the soldiers. In other words, the European Court of Human Rights has criticised the UK for failing to abide by the procedural, rather than the substantive, requirements of Article 2 ECHR. The participants agreed that there were inherent limitations in conforming to Article 2 ECHR obligations. Amongst the practical constraints mentioned were the lack of manpower and Human Rights and Military Operations the lack of effective control over the foreign territory in which British forces may operate. The participants also debated whether there were any justifications for failing to fulfil such obligations. One participant mooted that there should be a threshold of applicability of Article 2 ECHR. In other words, Article 2 ECHR should only be engaged when the armed forces are in control of the territory and able to engage and take on the responsibilities enshrined in that provision. A discussion on the difference between the inability and the unwillingness of the authorities to comply with such requirements then ensued. Maybe such a test (eg unable v unwilling) should be introduced when deciding not on the applicability, but on the application of Article 2 ECHR. Put differently, is it reasonable or even possible in a hostile environment to expect the forces to abide by the procedural requirements of Article 2 ECHR, given the circumstances? This may be contrasted with the Turkish cases brought before the Court, where the State had been unwilling to fulfil its Article 2 ECHR obligations. One participant pointed out that the Afghan cases that are likely to find their way to the European Court of Human Rights will no doubt prove that, assuming the Court finds the Convention to be applicable, the military has endeavoured to fulfil its Article 2 ECHR obligations to the best of its ability and has constantly adapted its policies and practices in light of case-law stemming from either national or European courts. In this context, flexibility is key. Certainly, in the eyes of the participants, willingness should be considered as a key factor to determining whether the armed forces have acted in conformity with Article 2 ECHR. Further, there seemed to be agreement amongst the participants that willingness must be assessed in light of the circumstances. Putting too onerous a burden on the armed forces will be viewed as unrealistic or unachievable by service personnel, all the more as in some circumstances it might put their lives as well as the lives of civilians in danger. Obligations under Article 2 ECHR To further explore the Article 2 ECHR obligations, Dr Quénivet proceeded to examine such duties in a chronological manner: prior to the deployment of the armed forces, during the deployment, and after the deployment (ie at the investigation phase). Pre-Deployment Obligations Two issues emerge with regard to Article 2 ECHR obligations relating to acts prior to the deployment of a military operation: planning the operation and training the individuals taking part in the operation. 9 Human Rights and Military Operations The McCann case is no doubt the most suitable basis for discussion, since the operation was carried out by members of the armed forces. In that case, the European Court of Human Rights attached particular importance to the fact that an opportunity to arrest the individuals had not been taken. The participants acknowledged that as the operation was not undertaken in an armed conflict, a law enforcement, rather than a conduct of hostilities, paradigm was indeed applicable. Could the requirements set out by the Court be transferred onto military operations in the context of active hostilities? Would such requirements be identical? Many participants expressed concern over a complete transfer of the principles and standards applied in McCann to combat situations, bearing in mind that the circumstances are wholly different. It was argued that the application of the law enforcement paradigm in such situations would neutralise the ability of the armed forces to act as a military force engaged in an armed conflict. That being said, it was acknowledged that even in the context of armed conflict, the armed forces capture individuals, rather than lethally target them, although in many instances capture was not a feasible option. Here the participants mentioned the killing of Bin Laden, though stressed the specificity of that case. It should be noted as levels of violence in theatre fluctuate it is difficult to determine which legal framework is applicable and, in particular, whether the ECHR applies.. The European Court of Human Rights also stated in McCann that all assumptions about the individuals to be arrested and their activities must be 10 thoroughly reviewed. One participant enquired about the threshold of evidence required to arrest and charge a person. How much evidence would be sufficient in the context of combat operations? In the McCann case, the European Court of Human Rights examined the kind of training given to the military forces deployed and, especially, whether they had experience of training and use of weapons in a law enforcement context. The overall experience of the individuals deployed was also assessed. The participants agreed that in light of the thorough training and instructions given to members of the armed forces, complying with this training requirement should not be overly difficult. Human Rights and Military Operations Obligations during Deployment (and Derogations) As mentioned earlier, cases brought against the British armed forces never found the UK in violation of the substantive obligations under Article 2 ECHR (in Al-Skeini and others v UK the applicants did not even raise such claims). Dr Quénivet nonetheless reminded the participants that in cases brought against Russia, the European Court of Human Rights had reviewed steps taken in the conduct of operations against the standards of the ECHR, such as the lawfulness of the use of certain weapons and the importance of minimising the use of lethal force. Dr Quénivet pointed out that in these cases, the Court had rather surprisingly used a language close to that of international humanitarian law, referring notably to civilians, conduct of hostilities, and the principle of distinction. The Court relied on a stricter standard of review than what is found in international humanitarian law, which uses a test of excessive use of force against civilians and civilian objects ‘in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated’ (Article 51(5) Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts). One participant observed that although the conflict in Chechnya could be classified as a non-international armed conflict, Russia had not derogated from the ECHR. It was thus not possible to claim before the Court that an international humanitarian law framework was applicable. The UK had never argued that Article 15 ECHR, the derogation provision, was applicable in situations of an armed conflict abroad. It had however done so in relation to the situation in Northern Ireland. One participant stressed that the traditional view was that Article 15 ECHR could only be invoked in situation of a war threatening the life of the nation. This could not necessarily be said of recent military operations abroad as, for example, it is unclear whether the situation in Iraq or in Afghanistan did threaten the life of the British nation within the meaning of Article 15 ECHR. This led the participant to ask whether derogations were available in an extra-territorial setting. Opinion on the matter was split. Some participants contended that the ECHR should not apply extra-territorially, an argument rebutted by another participant who pointed out that a reversal in the Court’s jurisprudence was unlikely. Another group of participants surmised that maybe not enough consideration had been given to the applicability and potential utility of the derogation provision in the context of extra-territorial deployments. Obligations after the Operation As the European Court of Human Rights has found the UK (as well as other States) to have breached the procedural requirements of the ECHR in the wake of a military operation, much attention was devoted during the discussion to considering the reporting and investigatory duties of States. The European Court of Human Rights has clearly stated that such procedural obligations exist even in difficult security conditions, including in an armed conflict (see Jaloud v The Netherlands). 11 Human Rights and Military Operations The discussion turned to after-incident reports and their use by the armed forces. In particular, such reports assist the armed forces in holding their members accountable against internal rules and procedures. If such internal rules and procedures, which reflect the current law and the best practice at the time, are found to be deficient, they can be reformulated, thereby facilitating the internal review process. Such reports enable the armed forces to learn valuable lessons by identifying areas of concern and training needs. It was also noted that there are review procedures in place for more serious and complex matters where an investigation might be warranted. Such internal rules are not a substitute for the law, they only assist in the implementation of the law. With regard to the investigation, a number of participants noted that compliance with the procedural aspects of Article 2 ECHR imposes an onerous responsibility on the armed forces, all the more as their size is shrinking and thus fewer individuals are able to carry out activities required by Article 2 ECHR. The size of the police forces in conflict zones is also too small for such forces to be promptly deployed. As the investigation must be effective, ie able to determine whether the force used was or not justified in the circumstances and, if not, to identify and punish those responsible (Hugh Jordan v UK), military police must be able to carry out their duties in an unimpeded manner. While the duty to carry out an effective investigation is not an obligation of result, but of means, complying with this duty is easier said than done. For example, 12 carrying out an effective investigation in a hostile environment may pose personal risks to the military personnel involved and to the surrounding civilian population. Similarly, operating in another State means that the UK must cooperate with the local authorities which may, for example, deny access to certain areas and persons or claim jurisdiction over specific individuals. In the recent case of Jaloud, the European Court of Human Rights conceded that some leeway should be granted to a respondent State owing to the fact that it was operating in a foreign State that was being rebuilt and whose language and culture was alien to the armed forces and investigators, and whose population included hostile elements. Undoubtedly, the Netherlands, which was the respondent State in that case, “...a point of concern … is the lack of clarity of the law as it develops by way of case-law.” faced a range of practical difficulties in carrying out an effective investigation. For example, one participant pointed out that Dutch personnel attempted to attend the autopsy of the person shot by the Dutch forces, but the Iraqi authorities prevented them from doing so. The European Court of Human Rights then held that the Netherlands had failed to take all necessary steps to ensure that the autopsy met the standards required for an effective investigation. Another participant argued that one of the reasons the Human Rights and Military Operations Netherlands might not have been able to explain its position well was probably because it had focused too much on the applicability of the Convention and jurisdictional issues rather than on the application of Article 2 ECHR. As a result, it may not have been in a position to present the full arguments to support its position. In this context, one participant wondered why the UK had not taken this opportunity to intervene as a third party and spell out its own position. After all, such cases present a unique occasion for States facing similar challenges in similar circumstances to shape the jurisprudence of the Court. It was pointed out in discussion that such interventions might be used in later cases against the States making such briefs. Conclusion A point of concern among the participants is the lack of clarity of the law as it develops by way of case-law. What is more, as each situation in which the armed forces operate is different (in- cluding the intensity of the fighting, authorisation by the United Nations Security Council, laws of the host State, and multinational operations), finding a one-size-fits-all policy is problematic, if not impossible. As a result, the armed forces constantly need to review their policies and procedures, but so far the armed forces have shown that they can adapt to new legal challenges. Flexibility is the key word. Towards the end of the session, the view was expressed that the continued focus on the applicability of the ECHR might divert attention from engaging with the question of the application of its provisions. In this respect, some participants suggested that it might be time to consider accepting the Convention’s applicability in certain circumstances, so as to enable the UK to argue cases before the Court in a more effective fashion. This in turn would open the door to making derogations in such circumstances. 13 Human Rights and Military Operations 3. Juridification of the British Armed Forces and Efforts to Fight Back: What Are the Options? Introduction The afternoon session focused on the policy options and practical means available to deal with the challenges presented by the applicability and application of human rights law (and more specifically the ECHR) in military operations. Dr Aurel Sari began by explaining that there was no point in fighting the juridification of the armed forces as such. Rather, it made more sense to understand the nature and extent of the challenges it presents and then investigate possible solutions. Juridification Process The concept of juridification was introduced into the present debate by Professor Gerry Rubin in an article published in 2002 in the Modern Law Review to describe the development of military law in the United Kingdom. According to Rubin, juridification went through three stages of development. In the mid-19th to 20th centuries, the armed forces enjoyed a position of relative autonomy from the rest of society. Whilst they were subject to civilian standards and remedies in the- mid-19th to 20th centuries • Autonomy 14 ory, in practice, the impact of civilian legal oversight over the armed forces was minimal. From the 1960s onwards, successive governments progressively aligned the legal standards and procedures applicable to the military with those applicable in civilian life, setting in motion a process of civilianisation. In the 1990s, a third phase, the juridification phase, started whereby civilian standards and oversight mechanisms were increasingly imposed upon the armed forces without their consent and approval. In his work, Rubin thus describes civilianisation as a consensual and internal process, whilst he characterises juridification as a non-consensual and externally driven development. Dr Sari argued that this distinction between juridification and civilianisation is not persuasive for a number of reasons, notably because the pluralism that now characterises the legal framework of the armed forces does not support such sharp distinctions between consensual and non-consensual processes and between their internal and external dimensions. For analytical purposes, it is therefore preferable to retain the term juridification as the overall concept describing the growing 1960s • Civilianisation 1990s • Juridication Human Rights and Military Operations extension of legal rules into the sphere of military autonomy and the increased density of these rules. It is clear that the process of juridification, including the growing impact of “...the growing impact of international human rights law poses significant legal challenges to the armed forces.” international human rights law, poses significant legal challenges to the armed forces. However, Dr Sari noted that the true nature and extent of these challenges and their effect on operational effectiveness are not clear. In particular, it is important to distinguish between the actual adverse consequences of legal constraints on operational effectiveness and their perceived consequences. Much of the evidence for the adverse impact of international human rights law on the armed forces is of an anecdotal nature. In this respect, the participants agreed that international human rights law has significantly affected the way in which the armed forces conduct their business, for instance in the field of military justice and the rules governing the sexual orientation of serving personnel. They also noted that international human rights challenges seem to have had only a relatively limited impact on operational effectiveness in many areas, thanks to the ability of the armed forces to adapt. Nevertheless, in other areas their impact has been more sub- stantial, as the Serdar Mohammed case illustrates. Dr Sari then stressed that the law now extends into previously unregulated areas and that the growing density of the law, including the proliferation of oversight mechanisms, has contributed to the impression that juridification might have gone too far. The AlSaadoon and Mufdhi case was mentioned by one participant as a good example of how legal, rather than policy, considerations are sometimes prioritised. The participants also emphasised that States seem to have fewer opportunities and less leeway in shaping the law that applies to their armed forces on the national and international level. This means that the Government has fewer options to effect change and address unwelcome developments in the regulatory framework. 15 Human Rights and Military Operations The participants also considered the relationship between domestic and international law and the relationship between legal and social change. In this context, some of the participants observed that certain sections of civil society seem to pursue a clear litigation strategy against the armed forces, thereby affecting the way we look at (international) security, which is now increasingly viewed from a human rights prism. One participant questioned whether the application of human rights abroad would not lead to some form of ‘human rights imperialism’, as the armed forces are obliged to comply with the ECHR in territories that do not belong to the legal space of the Convention. Does this mean that armed forces are exporting European human rights to other territories? Whilst human rights are understood to be universal values and their application abroad should be welcome as a means to disseminate human rights law, it was also pointed out that it was a European variant that was being spread. One participant observed that, by contrast, international humanitarian law does not know of regional variants and its application in theatres like Afghanistan and Iraq did not raise the same difficulties. In re- 16 sponse, another participant noted that there seems to be a growing tendency to view international humanitarian law from a religious perspective. For example, a number of courses in international humanitarian law integrate religious elements, so as to appeal to a wider audience. The role and influence of military legal advisers was stressed at several points in the discussion. One participant observed that in the 1960s civilian practitioners joined the services as lawyers and injected civilian standards into the military legal system and in particular into the military justice system. It was also highlighted that human rights litigation had prompted changes to practices which at the time did not enjoy unqualified support within the armed forces, such as discrimination based on sexual orientation, and that these changes had in fact been quickly accepted by the armed forces. It was also noted that for the latest generation of lawyers, the Human Rights Act, and human rights considerations more generally, have been part of their professional life from the outset. Bearing in mind the complexity of the legal and practical questions raised by the application of human rights law to deployed operations, it was recognized that there is a need to train constantly military legal advisers in this specific area. However, another participant explained that training cannot provide for every eventuality and, if the law changes too quickly, violations are likely to happen. Human Rights and Military Operations The group then turned its attention to the extra-territorial applicability of human rights law, noting that the application of human rights obligations in deployed operations presents concrete, practical difficulties. The discussion quickly moved to the interrelationship between human rights law and international humanitarian law. The point was made that international humanitarian law is strengthened by human rights law in the sense that human rights law obliges the armed forces to establish robust procedures and safeguards. The participants nevertheless agreed that there are instances where the two legal regimes clash and where the scope for normative compromise is limited or non-existent. Likewise, the participants raised the issue that it should be possible to strengthen the application of international humanitarian law by an application of the lex specialis principle. After all, a number of courts have used this principle to solve methodological problems. However, one participant pointed out that this principle is not as well established in international law with regard to the interrelationship between international humanitarian law and human rights law as it is often claimed. Strategic Approaches to Addressing Juridification Further thoughts were given to adopting a more strategic approach to dealing with the challenges caused by the juridification. Three strategic options were examined. Reversing the Juridification Process It was agreed that it would be hard, if not impossible, to reverse the juridification process, as it is not a deliberate process. One participant drew a parallel to the 9/11 attacks, pointing out that the attacks led to major changes in international law and even a shift in paradigms. Fundamental changes of this nature could not be made or reversed deliberately. If this is so, the group debated whether it would be possible to slow down the process or maybe steer it. While this may be a more realistic aim than attempting to reverse juridification, the participants noted that human rights standards and discourse have become Strategic approaches to addressing juridification Reversing the juridication process Eliminating legal complexity and uncertainty Mitigating complexity and uncertainty 17 Human Rights and Military Operations an integral part of the legal environment. For example, even if the UK were to withdraw from the ECHR, it would still remain subject to human rights obligations deriving from other sources of law. Human rights have also entered common law. One participant stressed that the ECHR would apply via the EU Charter on Fundamental Rights (unless the UK withdrew from the European Union too). Consequently, the chances of stopping juridification in this area appear to be limited. Eliminating Legal Complexity and Uncertainty The participants agreed that it is the very nature of law to be formulated in an abstract and general manner as it is meant to apply to a variety of situations. As a result, the application of the law to specific circumstances can be uncertain. Legal systems and regimes, be they national, European or international, are social processes. As such, they need to be flexible to fit changes in society, which constitutes a further source of uncertainty. The application of the law is therefore riddled with complexity and uncertainty. Yet, it is the job of lawyers, courts and other legal actors to navigate these difficult waters. Mitigating Complexity and Uncertainty It was agreed by the participants that the only true option is to mitigate the complexity and uncertainty of the law. For example, this could involve a systematic engagement with international human rights law in order to balance the legal requirements against military considerations. The partici- 18 pants also agreed that a comprehensive approach employing all available means and methods needed to be adopted to pursue this aim. “...the only true option is to mitigate the complexity and uncertainty of the law.” Proposed Solutions This led into examining the various means and methods that can or could be used to mitigate the complexity and uncertainty of the law. Dr Sari led the discussion by introducing the array of relevant measures identified in the public debate, in particular by the House of Commons Defence Committee’s report on ‘UK Armed Forces Personnel and the Legal Framework for Future Operations’. Fighting each case vigorously. All participants agreed that legal challenges brought against the armed forces in the courts need to be fought vigorously where appropriate. That being said, a number of participants suggested that fighting the applicability of the ECHR in the context of deployed operations may no longer be an effective litigation strategy in particular cases. Given the stage of development in the European Court’s case-law, some participants therefore thought that it would be better to focus on the application of the Convention in specific cases. Human Rights and Military Operations Applying for derogations. There was disagreement amongst the participants as to whether derogations would be permitted in extra-territorial situations, in particular where armed forces were deployed abroad in the context of a non-international armed conflict. One participant explained that in the light of the Hassan case, it might not be necessary to apply for derogations, for international humanitarian law is being considered by the European Court of Human Rights as an international rule assisting in the interpretation of the Convention. Others expressed the opinion that we should not so easily dismiss the possibility to enter derogations under Article 15 ECHR. Two reasons were adduced: it is not possible to know whether the Court would have drawn similar conclusions if the facts of Hassan would have occurred in a non-international armed conflict and it cannot be taken for granted that the Court will not reverse its own jurisprudence in future cases. Using domestic law to prevent the application of human rights law. One of the proposals mooted was that Parliament should revive the relevant provisions of the Crown Proceedings Act, restoring the principle of combat immunity. This suggestion was rejected by the participants as impractical, since the European Court of Human Rights would continue to review such cases, irrespective of the existence of such domestic law. Strengthening international humanitarian law. Since international humanitarian law does not have a mechanism that enables individuals to bring claims against the armed forces to seek redress for alleged violations of international humanitarian law, human rights law is often used as an alternative mechanism. This suggested that strengthening the implementation and enforcement of international humanitarian law may indeed assist in meeting the challenges posed by human rights litigation. Another point made was that it would be beneficial if judges, both national and European, would recognise the role played by international humanitarian law in armed conflict and would receive 19 Human Rights and Military Operations appropriate training in this branch of international law. Affirming the primacy of international humanitarian law. Whilst affirming the primacy of international humanitarian law was welcome by the participants, it was also noted that human rights law complements international humanitarian law. Evidence base. All participants agreed that more evidence of the impact of human rights law was needed so as to craft an effective, tactical and strategic reply to address the relevant challenges. Amongst such challenges are the detention and targeting of individuals, the transfer of detainees and post-incident investigations. Further, it was noted that the armed forces should not lose sight of the issue of interoperability. Strategic Defence and Security Review. The participants opined that the Strategic Defence and Security Review was not an appropriate mechanism to deal with the challenges caused by the applicability and application of human rights law in military operations abroad. Legal training and advice. Whilst the participants agreed that enhancing legal training across the armed forces and increasing access to legal advice were helpful, some participants ex- 20 plained that it is only possible to train individuals in areas where the law is clear and certain. It becomes complicated, if not impossible, to train individuals in grey legal areas. It was stressed that training must be offered at all levels and in a diverse manner so as to facilitate the acquisition of the relevant legal knowledge. Conclusion The participants agreed that the juridification process could not be stopped. However, it could perhaps be steered so that changes in the law do not feel imposed on the armed forces. The armed forces have learned that they need to be flexible and constantly adapt to respond to a dynamic operational environment. The participants agreed that in many instances the armed forces should be able to adapt in a similar fashion to a dynamic legal environment, including the changing case-law of the European Court of Human Rights. Many participants supported a strengthening of international humanitarian law which, they hoped, would lead to fewer cases being brought against the armed forces under human rights law. The derogation clause in the ECHR was also viewed as an option that needed to be given further consideration. Human Rights and Military Operations 4. Conclusion By way of conclusion, the authors of the present report offer the following thoughts and reflections. 2 The proceedings have confirmed that at this stage a better understanding is needed of the practical implications of the human rights obligations applicable the UK armed forces deployed abroad. Interestingly, the concept of military effectiveness was barely broached in the discussions. Rather, the participants focused on the relationship be- The following key lessons and points have emerged from the workshop. “...a better understanding is needed of the practical implications of the human rights obligations applicable the UK armed forces deployed abroad.” tween international humanitarian law and human rights law more generally. Whilst some participants wished for the supremacy of international humanitarian law to be declared, other participants, adopting a more conciliatory approach, accepted that human rights law was also a relevant legal framework that needed to be taken into account to determine the lawfulness of the actions of the British military forces. More work needs to be carried out so as to clarify the legal framework of deployed operations, in particular in relation to detention, targeting, the transfer of individuals and post-incident reports. The UK should continue to invest in the training of its armed forces, as constant flexibility and adaptability is needed to confront the legal and practical challenges outlined in this report. While litigating the applicability of international human rights law to overseas military deployments remains relevant in many cases, this should not detract attention from engaging with the modalities of its application in this context. The Strasbourg Court’s judgment in Hassan underlines the prospects and challenges of such an engagement. With the foregoing in mind, it remains relevant to explore the applicability and utility of Article 15 ECHR, the derogation provision, in extra-territorial settings. Accordingly, these conclusions are those of the authors. 2 21 Human Rights and Military Operations About the Authors Dr Noëlle Quénivet is an Associate Professor in International Law at the Department of Law of the University of the West of England (United Kingdom). Prior to holding this position she worked as a Researcher at the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (Germany) where she taught on the MA in Humanitarian Assistance (NOHA) and the MA in Human Rights and Democratisation (EMA). Outside of higher education, she teaches for the International Association of Professionals in Humanitarian Assistance and Protection and has previously been involved in the delivery of classes to members of the Red Cross and Red Crescent societies, military legal advisers, prosecutors and judges. She has published several articles relating to international humanitarian law, authored Sexual Offences in Armed Conflict in International Law (2006 winner of the Francis Lieber Honorable Mention Award) and co-edited two books, one on the relationship between international humanitarian law and human rights law and another on international law in armed conflict. Her research focuses on international humanitarian law, international criminal law, post-conflict reconstruction, and gender and children in armed conflict. Dr Aurel Sari is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Exeter and a Fellow of the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps. His research interests lie in the field of public international law, with a particular focus on the legal aspects of military operations. He has published widely in leading academic journals on status of forces agreements, peace support operations, the law of armed conflict and other questions of operational law. Dr Sari maintains close working relationships with the professional community and lectures regularly on the subject of international law and military operations in the UK and abroad. He contributes to the work of several international bodies active in this area, including the ILA Study Group on The Conduct of Hostilities under International Humanitarian Law and the Committee. Dr Sari is the founding director of the Exeter Research Programme in International Law and Military Operations, which provides a focal point for the study of the international legal aspects of contemporary military operations by bringing together experts working in this field at Exeter. He is an affiliated member of the Strategy and Security Institute. 22 Human Rights and Military Operations About the Project This occasional paper forms part of a research project exploring the impact of international human rights law, in particular the European Convention on Human Rights, on overseas military operations. Funded by the British Academy, the project aims to develop a more sophisticated understanding of the challenges posed by international human rights law and its real and perceived impact on military operations. In doing so, it contributes to an ongoing public and academic debate about the legal regulation of the British armed forces. Led by Associate Professor Noëlle Quénivet (University of the West of England Bristol) and Dr Aurel Sari (University of Exeter), the project involves a series of workshops and other research activities over a period of two years. 23