SUPRASEGMENTALS AND COMPREHENSIBILITY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN ACCENT MODIFICATION A Dissertation by

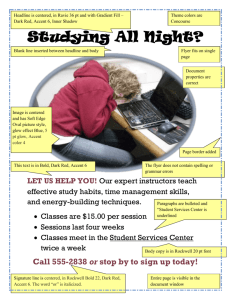

advertisement