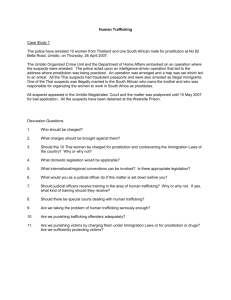

advertisement