Progress and Opportunities: Challenges and Recommendations for Montreux Document Participants

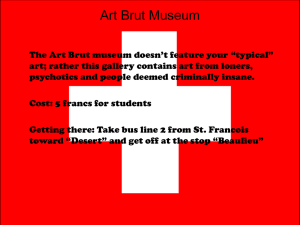

advertisement