Cultural Borders and Mental Barriers: William W. Maddux Adam D. Galinsky

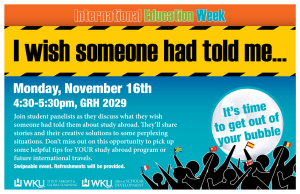

advertisement