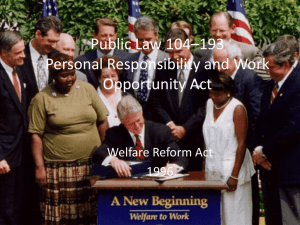

Income Support and Social Services for

advertisement