Commercial Poultry

advertisement

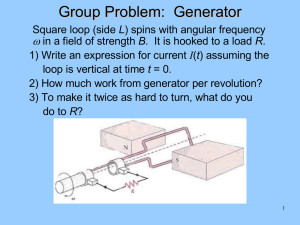

Commercial Poultry V O L U M E 2 , I S S U E 1 N E W S L E T T E R J U L Y 2 0 1 3 Financial Assistance for Maryland Growers INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Financial Assistance for Maryland Growers 1 Poultry Pollution Has Been Overestimated, UD-led Study Finds 2 From Bright to Dim—Some of the Good and Bad About LED Lights 3 From Bright to Dim-continued Has Your Standby Generator Had Its Annual Check Up? 4 5 The Maryland Agricultural and Resource-Based Industry Development Corporation (MARBIDCO) has a mission to help young and beginning farmers to buy their first farms as well as to assist existing farmers with expanding or diversifying their business operations. Since MARBIDCO's founding in 2007, more than 200 farm and rural business projects have been funded through a dozen programs that MARBIDCO offers. MARBIDCO has helped to fill a significant void in the private capital and credit marketplace by providing needed "gap" financing assistance to poultry growers throughout the Eastern Shore. Over the last five years MARBIDCO has made 13 loans (totaling about $3.4 million), that have been used to start or expand poultry farms in six Maryland counties, including four in Wicomico County, three in Caroline County, two in Dorchester County, two in Worcester County, and one each in Queen Anne’s and Talbot counties. Ten of these loans (or 77%) went to help young or beginning poultry farmers and all were done in conjunction with commercial lenders. MARBIDCO’s most popular loan program, the Maryland Resource-Based Industry Financing Fund Program (MRBIFF), has become an increasingly effective program in helping growers. The MRBIFF program makes lower-cost capital available to qualified producer applicants for the purchase of farmland and capital equipment. All MRBIFF direct loans are made with the participation of a commercial bank or farm credit association. The maximum MRBIFF loan amount is $200,000 for acquisition of equipment and fixed assets and $400,000 for real estate purchases or renewable energy projects. This program complements the financial services offered by private commercial lenders by helping make rural business gap financing both available and affordable. In addition to the MRBIFF Program, one of MARBIDCO’s specialty lending programs can provide assistance to poultry producers (thanks to the financial support provided by the Maryland Energy Administration). The Rural Business Energy Efficiency Improvement Loan Fund allows poultry growers to apply for an unsecured loan from MARBIDCO to help finance the cost of purchasing and installing equipment or technology related to lowering businessrelated energy consumption. Loan amounts under this program can range from $2,500 to $30,000; with repayment terms tied to the anticipated energy savings of the project. This program also features a 10% grant in addition to the loan financing. The goal of this program, of course, is to help farms to reduce energy consumption and increase profitability. MARBIDCO is a quasi-public economic development instrumentality of the State of Maryland. Its mission is to help Maryland's farm, forestry, and seafood businesses prosper. For more information about MARBIDCO’s programs, call 410-267-6807 or visit www.marbidco.org. PAGE 2 Poultry Pollution Has Been Overestimated, UD-led Study Finds Originally Published in USA Today—The News Journal by Jeff Montgomery May 2013 Federal environmental programs have drastically overestimated the poultry industry's contributions to water pollution, according to a University of Delaware-led study that could trigger changes to river and bay cleanup plans around the country. James L. Glancey, a professor in the university's Bioresources Engineering and Mechanical Engineering departments, said that a multistate study, based on thousands of manure tests, found that actual nitrogen levels in poultry house manure are 55 percent lower than the Environmental Protection Agency's decades-old, labbased standards. The results could lead to a formal proposal as early as next month for changes to the Chesapeake Bay Program's six-state pollution forecasting model, used to guide a federally backed attempt to restore the bay's health and ecosystems and assign cleanup goals. "I think this is a precedent-setting kind of thing, but we're not quite sure how it's going to propagate through the United States," Glancey said after giving a briefing on the findings at the state Department of Agriculture on Tuesday. "Everyone's watching it, there's no doubt about it. The comments came during a wider session on recent research findings suggesting progress in efforts to to improve groundwater quality and reduce the number of Delaware waterways designated as "impaired" by runoff containing high levels of fertilizer-like nitrogen and phosphorus. In a statement released late Tuesday, the EPA said that the agency has been aware of the studies for more than a year, and that a committee with "diverse participation" had been formed to settle the issue in a timely way. "While we await submittal of additional data needed, we are hopeful the collective data will show that industry efforts to reduce nutrients in poultry litter is having a positive result," the statement said. "Any decision regarding the use of this information would be made by the Chesapeake Bay Partnership. " Federal and state environmental agencies have focused heavily on pollution from animal manure and "factory farms" across the country as a big part of efforts to eliminate bay and river dead zones and harmful algal blooms in recent decades. The Delmarva Peninsula's poultry industry became an early, major battleground for the issue during the late 1990s. Sewage treatment plants, septic systems and suburban runoff also are significant pollution sources, but researchers argued that overuse of poultry manure on farm fields sent huge amounts of nutrients into groundwater and surface streams. That contributed to conditions that can deplete oxygen levels in water bodies like Delaware's Inland Bays and the Chesapeake. Individual farms, major producers and state and federal taxpayers have spent tens of millions on agricultural control programs, studies and monitoring. Delaware eventually formed a separate Nutrient Management Commission to oversee certification of manure and fertilizer producers and users and to subsidize shipment of manure out of stressed areas. PAGE 3 Poultry Pollution Has Been Overestimated, UD-led Study Finds (continued) "Are the EPA's goals really valid and realistic?" Delaware Agriculture Secretary Ed Kee asked Tuesday. "In the little bit of expertise and experience that we had, we knew something wasn't right with poultry manure" assumptions. "I think farmers will welcome this," Kee added. "We're not as big a problem as the world thought we were." Glancey said that research in Sussex County concluded that poultry houses there generated 261,723 tons of manure for one year studied, far lower than the nearly 1.5 million tons assumed using EPA models. Genetic improvements in birds, improved growing environments and other moves to limit waste and pollutants have all had an effect on the industry's environmental footprint. Bill Satterfield, who directs the Delmarva Poultry Industry Inc. trade group, said that members of his organization have been aware of Glancey's work for about a year. "The assumptions being used today are based on conditions not relevant to how chickens are being raised today," Satterfield said. "The amount of pollution attributed to chicken manure, if the Delaware numbers are correct, are way off base." Chris Bason, director of the Center for the Inland Bays, said that he had not seen the UD figures but supports research aimed at verifying the assumptions of scientific models used to guide regulations. "It is clear that poultry science has significantly reduced the amount of nutrients in manure over the last decade and a half or so," Bason said in an email. "If the EPA was using old data then this would not have been reflected." The Inland Bays, like the Chesapeake, have nutrient levels that exceed federal standards and have been blamed for losses of habitat and changes in aquatic life. Regulations approved in 1998 set limits on nitrogen and phosphorus flows into the bays, with those limits in turn used to support reforms ranging from septic system elimination and upgrade programs to "best management practices" for farms. In previous columns, we have talked about some of the advantages and disadvantages of alternative lighting for poultry and other agricultural use. From Bright to Dim - Some of the Good and Bad About LED Lights Eric Benson, University of Delaware - Courtesy of The Delmarva Farmer, February 12, 2013 LED lamps have attracted interest in agriculture because they are much more energy efficient than conventional incandescent lamps. Dr. Susan Watkins at the University of Arkansas estimated that between 20% to 40% of the total electrical consumption in a poultry house is connected to lighting. More importantly, the electrical consumption associated with lighting represents one of the few areas where an individual grower can make management changes to improve profitability. PAGE 4 From Bright To Dim-Some of the Good and Bad about LED Lights (cont.) LED lamps are characterized by high durability and high efficiency at modest total light output. Typical manufacturer estimated lifespan for LED lamps is in the 30,000 hour to 50,000 hour range. In two studies at the University of Delaware using a commercially available nonagriculture specific LED lamp, lamps were cycled on and off up to sixteen times per day. In the first study, no LED lamp failures occurred and in the second, slightly shorter study, only one lamp failed during accelerated testing. That’s a good sign for LED lamps since it shows that even under stress, longer lifespans are realistic. Lamp efficiency is rated in terms of lumens (a measure of total light output) per watt (a measure of power consumption). Typical incandescent lamps are in the 6 to 18 lumens/W range while LED lamps are in the 20 – 75 lumens/W range. Again, that’s a strong point for LED lamps. LED lamps tend to put out less total light than some of the other technologies, but that’s less of an issue for poultry since the lamps are dimmed down for most of the grow-out. So what’s not to love about LED lamps? Not all LED lamps are equivalent. When we replace an incandescent lamp, the only thing we generally are concerned about is watt rating. With LED lamps, there are significant differences between vendors and models. For example, one lamp that was tested by the University of Delaware had vents that allowed dust to enter the lamp globe and block light within one broiler grow-out. Another LED lamp that was tested included a small fan inside the lamp structure, which again would be a concern. One lamp currently being tested has what engineers call “hysteresis”. Hysteresis means that when the light is being dimmed, it stops producing at one point. When you go to increase the light level, it doesn’t turn back on until a different point. That can become a problem when working with commercial lighting controllers, which assume equal operation under both increasing and decreasing light. Having said this, there are some very good, agriculture-specific lamps that are designed to avoid these concerns. LED lamps respond differently to dimmers. An incandescent lamp generally responds evenly (or as engineers like to say, “linearly”) to changes in the dimmer. This is not the case with LED lamps. LED lamp output doesn’t always change directly with changes in dimmer settings. Incandescent lamps generally dim down to the point where no light is visible. LED lights generally decrease to a point and then shut off. The point at which the lamps stop producing light is highly variable between manufacturers. One agriculture specific LED lamp stopped producing light at approximately 50% dimmer setting while another LED lamp stopped producing light at approximately 20% dimmer setting. Large-scale testing in commercial broiler houses has also shown that there can be lamp to lamp variability in dimmer response for lamps from the same vendor. One agriculture specific LED lamp stopped producing light at approximately 50% dimmer setting while another LED lamp stopped producing light at approximately 20% dimmer setting. Large-scale testing in commercial broiler houses has also shown that there can be lamp to lamp variability in dimmer response for lamps from the same vendor. The University of Delaware is involved in both small house and large-scale studies to determine the impact of alternative lighting on broiler production. The trials are ongoing and the results are pending; however, one thing that has become clear is that management can override any potential differences between lamps. PAGE 5 Has Your Standby Generator Had Its Annual Check Up? February 2012 Jennifer Timmons, University of MD Eastern Shore If you have chicken houses, chances are there is also a standby generator on your farm. The standby generator is probably one of the most important but, one of the most overlooked pieces of equipment on a chicken farm. I know, I know, your generator is tested weekly and it runs just fine. However, are you confident your generator would run for a week or more? Researchers at Auburn University published a newsletter discussing the issues encountered with standby generators during the storms last spring. This article will summarize some of the information found in this newsletter so you can be prepared in the event of a power outage. It is important to have enough diesel fuel stored on the farm in case the generator is required to run for a long period of time. It is recommended to have at least enough fuel on the farm to run your generator for the first 24 hours of a power outage. The manual for your generator should provide you an idea of how much fuel your generator uses per hour. Conditioning and mixing stored fuel is also very important. Diesel fuel that has been stored for many years without conditioning and mixing can form sediment that settles at the bottom of the tank. When a near empty storage tank is refilled, the addition of the fuel disturbs the sediment at the bottom of the tank and puts it in suspension throughout the entire tank. The sediment can clog the fuel filter and prevent the generator from working. One suggestion to help reduce the risk of fuel filters clogging is to refill the tank before it has reached the half empty mark. Another fuel storage issue is water contamination usually caused by condensation. The authors suggest the fuel be checked twice a year for water using a water-finding paste. The paste can be placed to the end of a rod and submerged into the bottom of the tank to test for water contaminated diesel fuel. If the paste changes color, then your fuel is contaminated with water. It is also recommended to keep extra fuel filters on the farm in case the filter does clog from the sediment at the bottom of the tank. Clogged fuel filters cannot be cleaned sufficiently to clear the clogged filter. During a catastrophic event, local stores might not be open; therefore, you would not be able to pick up extra filters. Keeping two to three spare filters on the farm would allow you to replace the filter and restart your generator. Inspect and clean the transfer switch electronics annually. It is common for wasps, yellow jackets, and even rodents to build their homes within this equipment causing damage. It is recommended to contact a trained professional to inspect and test the transfer switch and electronic controls on the generator due to the complexity and expense of these electronic controls. The authors also suggest installing a manual by-pass key switch, if your generator does not have one. A manual bypass key switch allows you to manually start the generator, if the electronic controls fail. An electrician can install these switches for around $1,000, depending on the generator. A generator should be ventilated so it does not overheat and stop working. An enclosed generator should be ventilated similar to tunnel ventilation. The authors state the exhaust air from the radiator of the generator must exit the building through an opening 1.5-2 times the size of the radiator of the generator and installed directly in front of the radiator. The air inlet for the generator should be twice the size of the exhaust outlet and in-line with the generator. Standby generators are not intended to be installed and forgotten. The equipment must be serviced, tested, and inspected annually by a trained professional. Generators should also be serviced immediately after any periods of long run-time, of 48 hours or longer. It is important to become acquainted with your generator service person. Keep the contact information of at least two generator service persons in the generator shed so that it is easily available for anyone on the farm to find in case of an emergency. The generator is probably one of the most important pieces of equipment on a chicken farm. Preventive maintenance, along with some advance preparation, will ensure your generator is ready to use during any power outage situation. COMMERCIAL POULTRY