CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

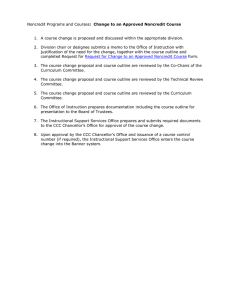

advertisement