CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE I

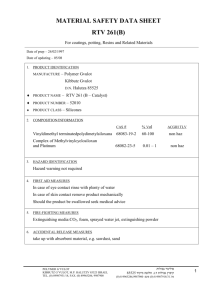

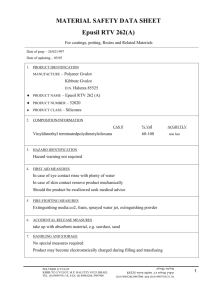

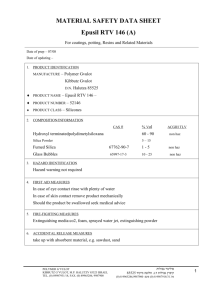

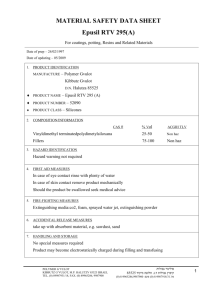

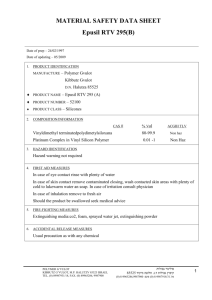

advertisement