Does SCHIP Spell Better Dental Care Access for

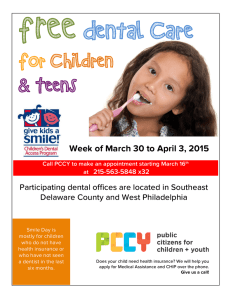

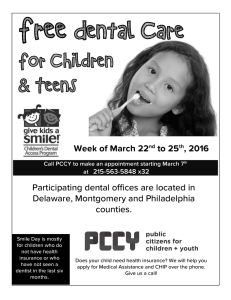

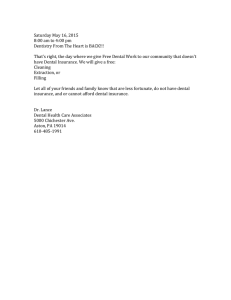

advertisement