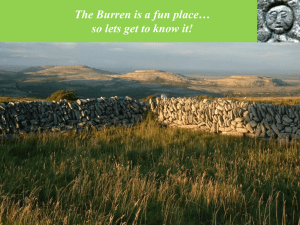

B L S U

advertisement