Part III: History as Social Science: Statistics, Summaries, Conclusions,

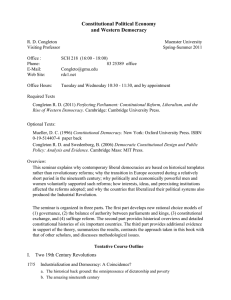

advertisement