An Assessment of Services Provided Under the American Final Report

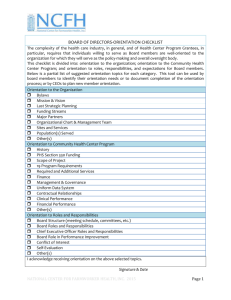

advertisement