EC742: Handout 3: From Public Economics to Public Choice and... Public Economics

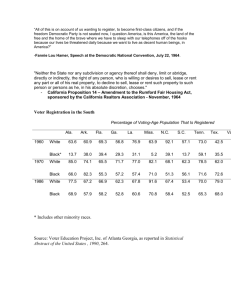

advertisement