Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life

advertisement

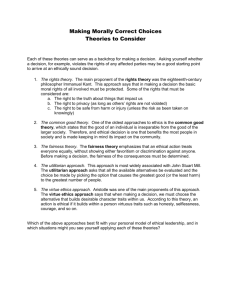

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life These revolutions periodically reshape the existing structure of industry by introducing new methods of production— the mechanized factory, the electrified factory, chemical synthesis and the like; new commodities, such as railroad service, motorcars, electrical appliances; new forms of organization—the merger movement ... Every piece of business strategy acquires its true significance only against the background of that process and within the situation created by it. It must be seen in its role in the perennial gale of creative destruction; it cannot be understood irrespective of it or, in fact, on the hypothesis that there is a perennial lull (Schumpeter, J. [1942/2012], Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy [KL 1519–1521, KL 1844–1847]). I. On the Possibility of Progress A. Introduction Neoclassical economics and most ethical theories were developed to explain and evaluate relatively stable social and economic systems. There is no use of the words progress or growth in Drebeu’s (1959) classic book on general equilibrium theory. Markets reach equilibrium through price adjustments that set supply equal to demand in both the short and long run. There is no use of the word progress in Rawl’s theory of justice. The word innovation appears just a single time. Principles of justice emerge from a reflective equilibrium. Ethical principles are regarded as timeless by other philosophers as well. It was in reaction to earlier equilibrium-based 1 economic and ethical theories that Schumpeter suggested a new model of economic progress and Spencer developed his evolutionary theory of ethics.1 This chapter explores how ethical dispositions affect economic development. Ethics plays many roles in dynamic economic and social systems. Ethics can provide an impulse for economic development insofar as innovations in ethical theories create new opportunities for exchange and team production. Personal ethics may support innovation and experimentation. Civil ethics may support laws and political institutions that allow or promote economic development or may attempt to retard them. It bears noting that the notion of progress itself is partly an ethical concept. To say that change occurs is not to say that the results are good; many are not. To say that at least some changes are good is to argue that such changes improve our character, or move us closer to the good or ideal society. That such improvements are possible has long been recognized. Aristotle, for example, considers ethics to be a method of self-improvement. Smith regarded the system of natural liberty to be an improvement over the medieval system that had previously characterized Great Britain. The belief that commerce tends to improve the quality of life has been less commonplace, although part I of the present volume demonstrates that that too has long been held by at least a subset of educated persons. That continual improvement is possible has been less commonplace. That innovation in a commercial society produces progress rather than degradation is partly a matter of one’s conception of the good life. If the good life is an active creative life, innovation will be praised and the stimulus provided by new opportunities enjoyed. Innovators will be praised by such persons and innovation considered a praiseworthy activity. However, if the good life is a life of stable patterns of life and thought, innovation may be regarded as a threat to the good life, rather than a complement to it. Challenges to one’s private equilibrium in such cases will be unwelcome and innovators and innovators subject to disapprobation, rather than praise. More recent critiques of the equilibrium view of social continued through the twentieth century, as in Schackle (1961), Kirzner (1973), Cowen and Fink (1985), Grossman and Helpman (1991), and Hanusch and Pyke (2007). It should be acknowledged, however, that these critiques and modeling extensions were minority views in economics for most of the twentieth century. Growth was acknowledged to be possible, but a tendency toward equilibrium growth paths was nearly always assumed. page 1 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life It bears noting that Schumpeter’s term “creative destruction” can be used to describe either the path to material comfort and longer lives associated with economic progress or a death spiral back to the short brutish and nasty lives of the Hobbesian Jungle. Either can be consequences of innovation. Figure 12.1 An Evenly Rotating Economy wages inputs B. On the Notion of Economic Equilibrium Neoclassical economics provides an explanation for the existence of an equilibrium in markets, what von Mises referred to as equally rotating systems, Schumpeter as the circular flow, and Debreu as a general equilibrium. Such an equilibrium can be shown to be a consequence of rational choice in well-known circumstances. Price theory demonstrates that a vector of prices can generate an all-encompassing equilibrium in production and exchange across all products and services through time in static circumstances when tastes are stable and well understood and no innovation occurs. In such circumstances, there is often a unique best choice for both consumers and producers. Those choices can be used to characterize individual, firm, and market equilibria. goods Output Markets Input Markets According to the early twentieth century assessments of Schumpeter and von Mises, the new more extended markets that emerged in the late nineteenth century were engines of transformation. Major innovations created new patterns that destroy or at least alter earlier ones. Lesser innovations induced significant modifications of previously existing patterns of life. They also argued that equilibrium notions of equilibrium may have applied to earlier social systems but not to capitalist ones. The term equilibrium can be regarded as a reasonable first approximation of a variety of systems at particular points in time, the orbits of the planets, the pattern of life in a stable ecosystem, the process of law making in a stable system of government, a stable pattern of production and exchange, and so forth. Change may take place within such systems, but so gradually that it can be ignored for the purposes of analysis or for those of a human life. spending Consumers inputs wages goods Firms revenues C. Cultural Equilibrium The result is a pattern of life and production that largely repeats itself, as with the farming cycle of a typical year, the holiday- and season-driven inventory cycles of grocery stores, or the cycles of human life. The life of farmers did not change quickly or radically for millennia at a time. It was largely driven by the seasons and fertility of their land. Celebrations tended to be associated with those same seasons and with the cycle of human life. Modest improvements in crops and techniques did occur, but for the most part life went on as before. The product mix of village stores and marketplaces also changed a bit from year to year as the color and cut of “fashionable” food and clothing varied, but the broad outlines of production and exchange were more or less stable and more or less repeated for generations at a time. When beliefs about nature and the good life are stable, successive generations learn the same natural and normative lessons, as parents and teachers repeat the wisdom of the ages to their children and students and as successive generations of scholars and intellectuals debate the properties of page 2 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life nature, the divine, epistemology, and ethics in a similar manner, with a similar focus and depth. Ethics and other routines of thought and conduct naturally tend to be stable in such periods. Such stable patterns of life were evident for much of history before the commercial society emerged. Many aspects of life in society may be stable even during periods in which knowledge is advancing. The formal institutions of a society may be stable in this sense. For example, the core legal institutions of the United States did not change in a major way during the past two centuries, a period in which knowledge changed rapidly and economic life equally so. There were modest changes in the standing procedures of governance and law, but the general pattern of law and constitutional governance was not greatly affected. Law remained for the most part based on judicial decisions and precedent. Elections were held and policy decisions made by elected representatives from the constituent states. Such stable patterns of life and society were arguably typical in the world before the commercial society emerged. There are many societies that appear to have had an equilibrium character for centuries at time, as with the various Stone Age societies discovered by Western explorers during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many societies have exhibited considerable stability in terms of common ethical and natural beliefs, patterns of production and consumption, and systems of government and law. Historians refer to stable periods with terms such as “age,” “era,” and “period.” Shifts from one “age” to another are often referred to as “revolutions,” as with the shift from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic period, the shift from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age and subsequently to the Iron Age. The term revolution is also used to describe changes in economic life that produced the commercial society, the Industrial Revolution. Part of the explanation for societies in equilibrium is the attraction that stable, reasonably comfortable patterns of life have for humanity. After a perturbation or crisis, a return to the preexisting equilibrium patterns is very likely when most persons prefer the certainty and comforts of the recent 2 past to change. Only if a return to familiar patterns is impossible will changes be grudgingly adopted by such conservatives. Innovations are discouraged in such societies as deviant behavior, mistakes to be avoided, or at best passing fads soon to disappear, rather than new possibilities to be fully explored. Several early Chinese innovations seem to have been under appreciated because of such conservative dispositions, including at least two innovations that subsequently changed the world: steam propulsion and gun powder.2 A society populated by social conservatives would clearly resist the dynamic nature of societies with extensive open markets. The idea of the universe which prevailed throughout the Middle Ages, and the general orientation of men’s thoughts were incompatible with some of the fundamental assumptions which are required by the idea of Progress…Again, the medieval doctrine apprehends history not as a natural development but as a series of events ordered by divine intervention and revelations. If humanity had been left to go its own way it would have drifted to a highly undesirable port, and all men would have incurred the fate of everlasting misery (Bury, J. B. [1921/2011, The Idea of Progress: An Inquiry into Its Origin and Growth [KL 321–332]). Whether such evenly rotating societies are the only ones possible in the long run or not is beyond the scope of this volume. Many but not all social scientists have assumed that to be the case. Historically, it may be argued that truly dynamic societies in which progress, as opposed to instability, is a defining characteristic are not commonplace. Most of us prefer our comfortable routines to change, often quite sensibly. Many of our routines were painfully worked out through a long process of trial and error. That variety may be the spice of life is not always intuitively obvious. Note that the term “under appreciated” is normative and for most persons in the West an unexceptional interpretation of these Chinese “mistakes.” This perspective itself reveals a more appreciative perspective on scientific and economic development, that is to say incorporates the idea of progress. A true conservative would regard the Chinese behavior as appropriate and unexceptional. page 3 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life II. On the Nature of Progress In opposition to what might be called social conservatism is the idea of progress. Some changes are for the better. However, determining whether progress is taking place is not as easy as one might first believe. One cannot simply assert, for example, that an increase in all goods and services makes everyone better off. At some point, increases in food and drink tend to reduce, rather than increase, both pleasure and life expectancy. Satiety sets in, our space becomes cluttered, and our bodies too heavy for pleasant exercise. How to determine whether progress is taking place in the short or long run is not entirely obvious. A dynamic life is not necessarily a better or more attractive one. Uncertainty can enhance life by keeping it fresh and interesting, or it can threaten it by undermining one’s core ideas and routines for living and placing individuals under more stress than is comfortable or character enhancing. The idea of progress requires both a long-term perspective and a metric to assess the changes taking place. The concept of progress is always evaluative and usually normative. It asserts that some change is an improvement. Some changes are more easy to discern and evaluate than others. Improvements in technology are relatively easy to recognize. A new machine that does everything that its predecessors did and more would clearly be an improvement as long as “more” is a desired result. The same might be said of a society. However, a machine or society that broke down more often than its predecessors would not necessarily be regarded as an improvement even if in other respects it dominated earlier machines. Some metric of “improvement” is always necessary. Not all change is for the better. 3 The “distance” to a hypothetical ideal state can serve as such a metric. A society that gradually approaches an upper bound of knowledge might gradually approach an equilibrium state of the ideal Spencerian variety but never reach it. Such a society might be said to exhibit progress, a form of instability that tends toward “improvement,” here in the sense that a human society gradually approaches the best possible one. If nature and society are so complex that no upper bound of knowledge exists or only one that is so distant that it not likely to bind humanity in the foreseeable future, improvements in the rules and the product mix of a society may continue forever without converging to some limiting ideal case. A path of transformation need not be smooth or obvious to be recognized as progress. If knowledge increases in discrete steps of different and unpredictable sizes, the changes induced tend to be unpredictable and of varying magnitudes. The associated crises may provide adaptations that in the short run may be regarded as the opposite of progress, as retrogressions or disasters. In such case, a general trend of improvement might be evident only after a relatively long series of innovations and adjustments have taken place. It is such long-term series of improvements that are referred to by the generalized notion of progress.3 Moreover, it is rarely the case that particular instances of technological change produce benefits for everyone. The variety and quality of horse-drawn wagons, buggy whips, and quills is far less than they used to be, although the variety and quality of automobiles, computers, and cell phones are much greater. Judging the degree of material progress requires an assessment of the gains and losses, and these are inherently subjective. Objective indices and averages such as GDP and GDP per capita can only approximate the net J. B. Bury (1921) provides a very nice intellectual history of the idea of progress. He notes that two broad conceptions of progress were present in the West during the nineteenth century (ch. 12). “Theories of progress are thus differentiating into two distinct types, corresponding to two radically opposed political theories and appealing to two antagonistic temperaments. The one type is that of constructive idealists and socialists, who can name all the streets and towers of ‘the city of gold,’ which they imagine as situated just round a promontory. The development of man is a closed system; its term is known and is within reach. The other type is that of those who, surveying the gradual ascent of man, believe that by the same interplay of forces which have conducted him so far and by a further development of the liberty which he has fought to win, he will move slowly towards conditions of increasing harmony and happiness. Here the development is indefinite; its term is unknown, and lies in the remote future. Individual liberty is the motive force, and the corresponding political theory is liberalism” (p. 236).The entire book is available online from the Gutenberg project: www.gutenberg.org/files/4557/4557-h/4557-h.htm#link2HCH0011. page 4 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life effect of a series of changes associated with episodes of innovation and economic development in commercial societies. As non-material aspects of life such as stress, the extent of virtue, quality of contemplation, or quality of family life are added to the mix, it becomes increasingly difficult to assess the net effects of change. The utility principle provides one possible all-encompassing index of the effects of such economic and social developments, albeit with the caveats mentioned by Spencer and others. If aggregate utility tends to increase with innovations in products and production methods, utilitarians would conclude that progress is taking place. Another possible system of evaluation is provided by contractarians. Contractarians would regard a series of changes to be progress if all persons in the community of interest regard the present society to be better on balance than the ones that preceded it. All individuals do not have to agree on the best measures of progress, it is sufficient that they agree that improvement has occurred. Different ethical systems may yield different assessments of the merits of economic development. As in previous chapters, it is those ethical theories that support material progress that are of greatest interest for the purposes of this volume. Many of these have utilitarian or contractarian foundations, although not all utilitarians of the twentieth century were proponents of the commercial society. III. Ethics and Economic Growth Theory Utilitarian and contractarian assessments of the relative merits of economic systems, as opposed to societies as a whole, can be undertaken in Pigovian manner by focusing on measurable sources of material comfort, holding other things being equal. There are problems with such an approach as noted by Pigou and indicated by the above, but it provides a good deal of plausible results about the effects of commerce on individual and human welfare. As a first approximation, the Pigovian approach simply argues that the greater the wealth or income of an individual or family, the greater are its opportunities for welfare enhancing activities. The greater those 4 opportunities are, the greater the realization of happiness or utility tends to be. Economic progress in this sense can be induced in a number of ways. The least disruptive of these was the first incorporated into economics. The early growth theorists analyzed how the accumulation of capital would affect an economy. Shortly after World War II, the mathematics of equilibrium growth paths was worked out. This new equilibrium concept implied that a commercial equilibrium need not be a circular flow; it could be a smoothly expanding spiral. Although, there are at least as many kinds of capital goods as there are final goods and services, the first mathematical models of growth assumed that just one homogenous type of capital, usually physical equipment. Human capital was added to the second generation of mathematical models. In general, capital increases the marginal product and marginal revenue product of labor, which implies higher real wages. A person can move more dirt with a shovel than his hands, with a wheelbarrow than without, and with a bulldozer than a wheelbarrow. Capital accumulation thereby increases both the output and the overall demand for goods and services. Human capital accumulation also tends to increase the productivity of labor and so has similar effects. The accumulation of either physical or human capital increases the outputs of previously produced products in the core neoclassical models. As a consequence, more consumers can obtain more of all the products they are familiar with, especially those produced with capital and knowledge-intensive methods.4 Of course, human capital is as varied as physical capital. Thus, from the perspective of neoclassical growth theory, much of this book can be thought of as an effort to understand the impact of changes in the subset of human capital that consists of internalized rules of conduct. Part II demonstrates that a subset of ethical dispositions have effects that are similar to other productive skills. They make individuals, firms, and markets firms more For an overview of early growth theory grounded in capital accumulation see Solow (1970). For an early model of economic development that includes human capital accumulation, see Romer (1990). page 5 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life productive by reducing agency, externality, and coordination problems and also a variety of risks associated with exchange and production. An increase in market-supporting ethical dispositions thus produces economic growth in a standard growth model for much the same reason that increases in other forms of human capital do. Toward the end of the twentieth century, the effects of the distribution and intensity of ethical dispositions in a given population were implicitly modeled and estimated in the new social capital strand of the development literature. A good deal of statistical evidence supported the hypothesis that increases in social capital increase income levels and growth rates.5 Although the term “social capital” applies most naturally to what we have termed civil ethics, personal ethics can also make societies more productive and pleasant places in which to live. Insofar as the spread and support of such values are regarded as signs of nonmaterial progress, social progress and economic growth can be mutually reinforcing, as argued by Bastiat, von Mises, and many others.6 the goods and services previously produced, and through innovations in production methods, rather than more of the same produced in familiar ways. Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) was among the first to recognize and analyze the distinctive manner of growth characterized by commercial societies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Writing in the first half of the twentieth century, Schumpeter argued that innovation and disruption were essential features of economic development. The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates (Schumpeter, Joseph [1942 / 2012-12-19]. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy [Kindle Locations 1823–1825], Routledge, Kindle Edition). Equilibrium models of growth have the nice property that economic development benefits essentially everyone. More goods and services are produced and real income rises for all. These effects are partly consequences of the equilibrium concept and party of assumptions about the nature of economic growth that tend to make it ethically uncontroversial, except to those favoring ascetic forms of life. However, capital accumulation is not the only or necessarily the main driver of economic development. New products obviously compete with older products for sales and inputs. Successful product introductions thus affect the equilibrium price vector and pattern of consumption and employment. Some prices rise and other fall. Some incomes increase and others are reduced. Similarly, new production methods such as the assembly line or computer-aided manufacturing reduce the cost of a subset of existing products either bankrupt their less efficient rivals or force them to make new investments in plant and equipment to remain competitive. IV. Innovation and Progress: The Process of Creative Destruction Less costly or higher-quality products may push former producers out of businesses that they had been in for years. Products that are no longer as useful become obsolete—as with wadding, buggy whips, or slide rules. They may no longer be produced. Indeed the words for them may disappear from common knowledge. Innovation is generated by especially creative teams of men and women who bring new production methods and products to factory floors and markets. Increases in the production of familiar products by familiar methods are only one of the many forms of economic progress. Much, perhaps most, of the economic development associated with a commercial society occurs through the introduction of new goods and services, the transformations of 5 For growth models that include the accumulation of social capital, see Routledge and Ambsberg (2003). Empirical evidence of the positive effect of social capital on economic growth rates is provided by Knack and Keefer (1997), Temple and Johnson (1998), and Beugelsdijk and Van Schaik (2005) among others. 6 See, for example, Güth and Kliemt (1994), Landa (1994), Ingelhart (1997), Pollitt (2002), or Tabellini (2010). page 6 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life A. Innovation Induces both Revolutionary and Evolutionary Changes in the Commercial Society brought into the capabilities of telephones as they became voice transmitting and receiving computers that also played music, took photos, answered Internet queries, plotted location and routes, and so forth. In extreme cases, as with the steel, telephone, electricity, the automobile, the computer, and the internet, innovations launch entirely new industries B. The Ethics of Innovation and alter the pattern of life as entirely new possibilities came into existence. Such transformative products are not simply stronger boards, faster letters, Both major and minor innovations often disrupt standing patterns of better candles, or horse carts, although they serve similar human purposes. life, making many worse off at the same time that benefits are provided for the innovators and their customers and input providers. As a consequence, Many innovations reduce the time required to provide the traditional the process of innovation raises a variety of ethical issues that do not exist in necessities and luxuries of life. Such innovations free time for leisure, work, smoothly expanding economies. Changes in market conditions associated play, and contemplation, at the same time that newpatterns of production, with innovation impose costs as well as benefits on the individuals living work, and play emerge. Other products introduced for use in leisure became within commercial societies. so central to life at home, that new "necessities" were created. Innovations do not all simply add another layer or more icing to a preexisting cake. Generally, however, in the capitalist system, with its rapid strides in improving human welfare, progress takes place too It bears noting that major innovations do not usually take place through swiftly to spare individuals the necessity of adapting a single revolutionary leap of imagination. Progress in such cases is obvious themselves to it. When, two hundred years or more ago, a in incremental improvements. Contemporary automobiles are still steered young lad learned a craft, he could count on practicing with a wheel, ride on rubber tires, and is propelled (for the most part) by a it his whole life long in the way he had learned it, gasoline engine with cylinders and spark plugs. The modern automobile without any fear of being injured by his conservatism. serves the same essential functions and is recognizably the same product. Things are different today (von Mises, Ludwig Nonetheless, a century of refinements have caused the modern [1927/2012]. Liberalism [p. 81]). mass-produced automobile to be very different from Henry Ford’s model T. Contemporary radios, heating and cooling systems, mapping programs, For those who lose their jobs or businesses as a consequence of innovation, Internet connections, and energy-saving shapes were beyond the imagination the effects can be as devastating as a major earthquake or fire. of the most creative engineers of 1908. Contemporary automobiles allow As a consequence, many of the economic and social effects of one to go farther on less fuel with far greater comfort than possible--indeed innovation conflict with both traditional norms and others more liberal in imaginable--with Ford’s “tin lizzy.” their orientation and history. For example, Mills argued that: Even more dramatic changes have occurred in many other “ordinary” [T]he fact of living in society renders it indispensable that products. For example, innovations in telephones during the past half each should be bound to observe a certain line of century produced devices that are less obviously telephones. Contemporary conduct toward the rest. This conduct consists, first, in telephones lack rotary dials and cords. They are interconnected through glass not injuring the interests of one another (Mill, J. S. rather than copper-wire networks. They use digital rather than analog [2013-08-16], On Liberty [KL 41041-41043]). encoding of sounds. These transformations radically improved the quality of sound associated with long distance conversations and allowed such This norm is violated every time a new product is successfully conversations to take place essentially anywhere. Additional tasks were also introduced, because such products nearly always reduce the income of page 7 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life persons producing rival products. New products that bankrupt rival companies may cause thousands to lose their jobs, many of whom face lower wages as their skills become obsolete, and lower wealth as housing near their former place of work falls in value. Mill argues that utilitarianism implies that government interventions may be appropriate in such cases: As soon as any part of a person’s conduct affects prejudicially the interests of others, society has jurisdiction over it, and the question whether the general welfare will or will not be promoted by interfering with it, becomes open to discussion. (Mill, J. S. [2013-08-16], On Liberty ([KL 41047–41049]). Rawls draws a similar conclusion when he states that Of course, liberties not on the list, for example, the right to own certain kinds of property...and freedom of contract as understood by the doctrine of laissez-faire are not basic; and so they are not protected by the priority of the first [equal liberty] principle (Rawls, J. [2003], A Theory of Justice [p. 52]). One cannot simply assert, as many economic text books do, that “pecuniary externalities” do not count. Such claims run counter to the utilitarian foundations of mainstream welfare economics and to contractarian theories of the good or just society. Innovation is one of the many cases in which a community might properly engage in regulation according to Mill and Rawls. And, of course, many have done so. Even innovations in food and clothing have been banned or regulated as with the various dietary and sumptuary regulations of medieval societies. 7 Given the unavoidable negative effects of innovations on the welfare of others, in what sense can it be moral to innovate? Both utilitarian and contractarian theories of civil ethics provide possible answers to that question. From the perspective of both utilitarian and contractarian analysis, what matters are the long term consequences of a series of innovations, rather than those associated with a single innovation. Is aggregate utility generally increased by a series of innovations, or not? From a contractarian perspective, the issue is whether essentially all persons anticipate being better off as a consequence of a long series of innovation or not? If so, establishing considerable liberty to innovate would be appropriate policy and innovation generally a virtuous and praiseworthy activity. If not, the status quo ante should be protected and innovations banned.7 Utilitarians require that innovations increase average utility in the society of interest. Contractarians require that innovations generate essentially net benefits for essentially all members of the community of interest. Utilitarians, unlike contractarians, also allow cases in which many expect to be harmed by innovation, as long as those advantaged gain more benefits than the innovations impose on those disadvantaged by them. If there is a consensus that the result is an improvement by whichever of these normative theories is used, then a contractarian and utilitarian case has been made for innovation over the status quo ante.8 In such cases, the result of innovation is considered to be “progress.” Other moral perspectives can also justify the process of innovation on procedural grounds. For example, if the essential features of civil law are accepted as Kantian universal rules, then behavior consistent with those rules is, by definition, moral or at least not immoral. Natural rights scholars may also stress procedural notions of proper behavior, noting that both innovations the individual persons adopting them have engaged in voluntary, lawful behavior. The victims of innovation have no right to block the innovators. Such rule and procedural-based arguments, however, need to Rawls (2003), for example, notes that inequalities induced by innovation are acceptable under his difference principle if the entrepreneur’s “better prospects act as incentives so that the economic process is more efficient, innovation proceeds at a faster pace, and so on” (p. 66). 8 Disagreements over the consequences of a series of innovations are, of course, possible. Agreement among utilitarians and contractarian theorists requires similar conclusions to be reached about the long run consequences of innovation. page 8 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life systematically distinguish between the damages imposed by innovators and those caused by thieves, arsonists, and murderers. If innovation is to take place, most inventions have to be exempt from both criminal law and the civil proceedings of tort laws. Clearly, the opposite conclusion could also be reached by placing greater weight on a person’s right to the status quo ante. It bears noting that without a long series of welfare-improving innovations, most consequentialist ethical theories would also have a difficult time concluding that innovation is a virtuous activity. If one accepts the principle that the freedom to swing one’s fist ends at the tip of another’s nose, one might naturally conclude that the freedom to innovate ends at another’s property values and income. This tends to be the proper utilitarian conclusion, if the net benefits from innovation have in the past been very small or negative. C. Ethics and the Politics of Innovation Conclusions about the effects of innovation partly determine the politics of regulation. For example, if only innovations that harm no other person are thought to be praiseworthy or acceptable, as is the case for fires, then only relatively minor innovations would be worthy of governmental approval or support. A farmer might invent a new method of planting or harvesting his or her crops, which arguably would increase his profits without harming any other, as long as it was not widely adopted. However, a major innovation would affect the farming practices of the entire industry, which would affect demands for labor, capital, and land, changing prices and the distribution of wealth. There would be many losers from such innovations, and these might be banned. Similar conclusions can also be drawn about innovations in non-economic spheres of life as well. Major new ethical, scientific, and religious theories also disrupt patterns of life, as they attract the time and interest of large numbers of persons in a given society. New dietary ideas may affect the demand for corn, wheat, beef, and fish. New religious ideas or interpretations may produce new organizations (sects) whose political influence may induce new laws and legal reforms. In a truly conservative society, only conventional ideas and behavior would be deemed praiseworthy or worthy of political support. If progress is widely believed to be possible and invention essential to it, such beliefs would also affect public policies. In democracies, this would occur though electoral pressure and moral suasion. In cases in which policy makers are insulated from such pressures, support for innovation would require the policymakers themselves or their critical supporters to have concluded that innovation produces sufficient progress to be worth the risk. If economic progress requires at least some freedom to innovate, civil and criminal laws would allow innovators to damage others in particular ways, as with the various price and wealth effects that economists refer to as pecuniary externalities. Innovations that destroy other businesses in a manner analogous to intentional or unintentional fires would be exempt from the criminal punishments associated with arson and any pecuniary damages associated with innovation would not be included among the bases for tort proceedings. Other policies such as patents and copyright production thought to increase rate of innovation might also be adopted. Support for public education (especially in areas where innovations seem likely), and subsidies and tax preferences for research and development might also be provided to further accelerate the pace of innovation. Without the conclusion that technological advance and commercialization are engines of progress or excellence, innovation is less likely to be supported informally through praise and encouragement or formally through legal exemptions for pecuniary damages. Differences in ethical systems can thus partially account for differences in the both the degree of economic development that has taken place in the past two centuries and for differences in innovation rates among contemporary societies. Far less innovation and industrialization would take place in conservative societies in which internalized norms tend oppose change itself or all conduct that harms others. More would take place in societies where widely held normative theories favored change or creativity and accepted damages as part of the cost of progress, as historically tended to be true in societies where utilitarian and contractarian theories are widely accepted. page 9 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life V. Reducing Uncertainty: Innovations in Risk Management The possibility of progress implies that the future course of life and society is not entirely certain or knowable. New ideas and inventions may occur at any time and many will induce individuals and communities to change many of their standing routines for life, and not always for the better. As uncertainties and downside risks become recognized, methods for coping with them will naturally be incorporated into both private and public routines. This is true at the levels of individuals, families, organizations, and governments. As commercial societies emerged throughout the West in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, economists began to carefully analyze the effects of uncertainty. Frank Knight (1921) was among the first to fully integrate risk and uncertainty into economic analysis. He noted, for example, that markets tend to produce specialization in various risk- and uncertainty-bearing services. Uncertainty thus exerts a fourfold tendency to select men and specialize functions: (1) an adaptation of men to occupations on the basis of kind of knowledge and judgment; (2) a similar selection on the basis of degree of foresight, for some lines of activity call for this endowment in a very different degree from others; (3) a specialization within productive groups, the individuals with superior managerial ability (foresight and capacity of ruling others) being placed in control of the group and the others working under their direction; and (4) those with confidence in their judgment and disposition to “back it up” in action specialize in risk-taking (Knight, F. [1921/2009-02-05], Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit [KL 3154-3159]). In the early twentieth century, several innovations in public policies were also undertaken to reduce risks associated with commercial societies and thereby make such societies more attractive. Examples include both unemployment insurance and efforts to manage the business cycle. These new policies took the merits of the innovation and the commercial society for granted and simply attempted to moderate or pool the risks associated with life in a commercial society. Many were formally risk pooling efforts analogous to private insurance. This is evident in their official names (which often include the term insurance), in their method of funding (often through earmarked taxes collected from labor income), and in the terms of eligibility for payouts (being temporarily unemployed). Such insurance-like policies did not interfere with the core processes of the commercial society but made them more broadly acceptable for the risk-averse persons living within them. However, other more radical policies were also considered during the twentieth century that might have eliminated the commercial society. Debates over such radical reform proposals included both ethical and economic arguments. VI. Reducing Uncertainty: On the Merits of Central Planning and Regulation The effect of specialization in risk bearing and risk pooling is to reduce risks for most persons and to make life in a commercial society more attractive. Such services and products do not reduce risks by reducing innovation but reduce the downside risks associated with innovation and 9 other unpredictable shocks such as weather that affect prices, salaries, and wealth. Innovations in risk and crisis management reduce, rather than increase, uncertainties although they may also disrupt previous patterns of life. Mid-twentieth century utilitarians moved beyond Pigou’s welfare economics to argue that an economy could, at least in principle, be directed by a utilitarian central planner who could eliminate commerce, much as More's magistrates did in his imagined utopia, while increasing aggregate utility. It was argued by some utilitarians that such a planner could increase aggregate utility by reducing uncertainty, improving the distribution of income, and eliminating externality problems.9 Such conclusions were See for example Lerner (1934) or Lange et al (1938). page 10 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life consistent with mainstream economic models of the twentieth century, which implied that a utilitarian ruler analogous to Plato’s philosopher king could improve on the commercial society by replacing it entirely or by administering a broad subsection of it. Indeed, Russia and its Soviet Union maintained that such a system was successfully being implemented in Northern Asia.10 This was a radical challenge to mainstream utilitarians, who had long favored commercial societies. This debate involved many technical economic issues, so it is unsurprising that the central planning debate took place largely among economists. What might be surprising is that much of the debate over central planning relied upon utilitarian reasoning.11 Those who challenged the conclusions of the proponents of central planning used several lines of attack. First, critics argued that using neoclassical equilibrium models as the foundation of their analysis generated a variety of misleading conclusions. The commercial society was far more innovative and dynamic than those models implied. Moreover, the implicit informational assumptions of neoclassical models implied that planners and market participants had far more information at their disposal than they are likely to have in reality. Second, they argued that the “first best” outcomes of utilitarian planning were not feasible. This was partly for similar reasons. Planners would not be able to produce an innovative society, nor would they have sufficient information to replicate the equilibrium allocation of resources generated by markets in the short term. It was also argued that the persons likely to become central planners are not likely to be utilitarians. Thus, the outcomes associated with even perfectly informed planning would not be likely to maximize aggregate utility or attempt to do so. As a consequence of all these factors, critics argued that the result of central 10 planning would far lower aggregate utility (as proxied by economic output) than generated by a dynamic commercial society. For example, Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992) reminded proponents of central planning that information is not freely available at a central depository but remains disaggregated in the minds of individuals. This, in combination with the heterogeneity of the knowledge that we each possess (and our ignorance), implies that planners would not know all that was necessary to coordinate the behavior of market participants as well as market prices do. It is useful to recall at this point that all economic decisions are made necessary by unanticipated changes, and that the justification for using the price mechanism is solely that it shows individuals that what they have previously done, or can do now, has become more or less important, for reasons with which they have nothing to do (Hayek, F. A. [1968/2002], “Competition as a Discovery Process,” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 5: 9–23). Hayek also argued that markets take account of far more information than a real benevolent central planner could. [T]he two advantages of a spontaneous market order or catallaxy: it can use the knowledge of all participants, and the objectives it serves are the particular objectives of all its participants in all their diversity and polarity. The fact that catallaxy serves no uniform system of objectives gives rise to all the familiar difficulties that disturb not only socialists, but all economists endeavoring to evaluate the performance of the market order (Friedrich Note that such a society, without markets but with ideal production and distribution, resembles Thomas More’s Utopia, with its sharing of labor and distribution squares. It seems clear that such a society could not exist without ethical foundations, insofar as shirking rather than working tends to be more prevalent when work is unrelated to salary than when it is. The ethical foundations for such a society are beyond the scope of the present volume. 11 A useful collection of essays on the original central planning debate was assembled by Hayek (1935), which has been reprinted several times. Interest in somewhat more limited forms of central planning continued after World War II, as in Tinbergen (1964). The arguments were not always conducted in terms of utility per se but, with respect to economic output and growth, more or less in the manner pioneered by Pigou. Late twentieth century commentary and critiques of central planning include Lavoie (1985) and Boettke (2002). page 11 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life Hayek [1968/2002], “Competition as a Discovery Process,” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 5: 9–23). In Hayek’s view, this ignorance extends to the common understanding of markets themselves. Even today the overwhelming majority of people, including, I am afraid, a good many supposed economists, do not yet understand that this extensive social division of labor, based on widely dispersed information, has been made possible entirely by the use of those impersonal signals which emerge from the market process and tell people what to do in order to adapt their activities to events of which they have no direct knowledge. That in an economic order involving a far-ranging division of labor it can no longer be the pursuit of perceived common ends but only abstract rules of conduct—and the whole relationship between such rules of individual conduct and the formation of an order which I have tried to make clear in earlier volumes of this work (Hayek, F. A. [1979], Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 3: The Political Order of a Free People [p. 162]). Another crucial issue was whether the central planner would tend to be benevolent or not (utilitarian or not), an issue that goes back at least as far as Plato’s and Aristotle’s analyses of government. Post-war public choice analysis suggested that the persons most likely to rise to positions of authority were unlikely to be utilitarians or altruists. The rapidly accumulating developments in the theory of public choice, ranging from sophisticated analyses of schemes for amalgamating individual preferences into consistent collective outcomes, through the many models that demonstrate with convincing logic how political rules and institutions fail to work as their idealizations might promise, and finally to the array of empirical studies 12 that corroborate the basic economic model of politics—these have all been influential in modifying the way that modern man views government and political process. The romance is gone, perhaps never to be regained. The socialist paradise is lost. Politicians and bureaucrats are seen as ordinary persons much like the rest of us, and politics is viewed as a set of arrangements, a game if you will, in which many players with quite disparate objectives interact so as to generate a set of outcomes that may not be either internally consistent or efficient by any standards (Buchanan, J. M [1984], “Politics Without Romance,” The Theory of Public Choice II). What Hayek, Buchanan, and many other economists suggest is that feasibility cannot always be deduced from economic models because the models abstract from many details in order to facilitate theoretical analysis, which cannot be ignored in practice. The disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1992 affirmed their conclusions. It revealed that Soviet planners had not been able to replicate the production efficiency nor the material comforts of Western commercial societies after more than a half century of active central management, nor could they be regarded as utilitarian in their choice of regulations and allocations of resources. In this case, differences in normative theories were arguably less important than differences in the predicted nature of central planning. The debate was largely among utilitarians or persons who had accepted the neo-utilitarian approach of Pigou. Nonetheless, assumptions about the ethical dispositions of the persons in the societies to be centrally managed were relevant. Clearly, a central planner that had internalized utilitarian theory would do better at maximizing aggregate utility--to the extent this can be discerned--than a pragmatist interested in maximizing his own income and authority. Clearly incentives matter less if all persons have internalized a strong work ethic and rule following norms.12 Much of the argument in favor of central planning It is interesting to note that markets tend to reward these core ethical believes insofar as they tend to increase firm profits, individual incomes, and consumer page 12 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life implicitly assumed a very complementary normative foundation for their society. Without that foundation, it was infeasible. circular flow tends to increase whenever market-supporting ethical dispositions become more commonplace or deeply held. Clearly, the course of public policies and life within the former Soviet Union would have been far different had their leaders been utilitarians rather than pragmatists seeking personal authority. They would still be limited by the information at their disposal and incentive effects on work, innovation, and adaptation to change. The results could at least conceptually have been better than they were, but are still not likely to have been as attractive as the associated with the commercial societies of the West. The formal institutions that frame choices in a community also partly determine the scope for commercial activity through their effects on internalized norms and by changing the marginal costs and benefits of different courses of action. VII. Conclusions: Ethics and the Commercial Society A. Ethical Foundations of a Commercial Society Human behavior is clearly the primary driver of economic activities. No other species engages in market activities. That opportunities for exchange and production are improved by the habits of mind that early philosophers referred to as virtue is less obvious, indeed entirely neglected in textbook economics. Of course, opportunities for commercial activity are also affected by scarcity and our understanding of the physical world, as emphasized by textbook economics, but without market supporting ethical theories and fewer of those opportunities tend to be realized--indeed fewer are possible. Part II of the present volume demonstrates that trading networks tend to be more extended and team production more productive when persons in the community of interest have internalized market-supporting ethical dispositions. Trade becomes less risky and economic organizations less prone to agency problems. The analysis of part II thus implies that the Chapter 11 suggests that both private and public legal systems are partly grounded in ethical beliefs. That informal rules of conduct precede formal ones is suggested by the logic of writing laws and by the gradual emergence of both civil codes and criminal laws.13 Although written rules have existed since the dawn of history, much, perhaps most, of what is codified in liberal societies reflects the informal ethical dispositions of the persons writing them. This is most evident in the English common law system with its jury trials--where the beliefs of ordinary persons determine what has happened and judges use their informed understanding of precedent to deal with both routine and novel cases. But formal civil law codes also emerge from theories of right and wrong conduct, including ethical beliefs about the role of commerce in a good society. The overlap between ethical systems and legal systems has been noted by such philosophers as Aristotle and Kant. The issue concerning the proper codification of ethical beliefs was also a concern of Bentham. Rawls emphasizes that constitutional law is or should be grounded in the theories of justice held by persons living in the community subject to its rules. That ethical theories play a continuing rule in economic development is implied by the same logic. Innovations in ethical theories themselves and the application of existing theories to new problems can generate changes in private behavior and public policies that promote or retard commerce. They satisfaction. Without such market rewards, it is clear that the distribution of internalized norms in centrally planned societies would be different than those of market-based societies. Market rewards for a work ethic and for rule following behavior tend to cause such ethical dispositions to be more commonplace and strongly internalized, as demonstrated in part II. 13 The law is another area in which bootstrapping takes place. Written laws are produced partly to solve practical problems and partly to formalize and record a subset of existing beliefs about proper conduct. The laws on the books, in turn, provide persons in those communities with examples of rules that it is important to internalized--both as a signal of community norms and to avoid punishments. Subsequent innovations in ethical theories and other norms, partly grounded in the written law, may induce legal reforms, and so on. page 13 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life may increase or decrease the risks and coordination problems associated with exchange and production. They may encourage reforms of legal systems that encourage or retard commerce and technological advance. After 1900, more specialization was evident in Western academics with the result that fewer persons wrote on both ethical and economic issues. As a consequence, ethics largely disappeared from economic texts, except insofar as Pigou's utilitarian ideas continued to provide the foundation for welfare economics. B. The Ethics of Economists Among economists, disagreements about reform and regulation often reflect disagreements about matters of fact and consequence, that is to say, on positive as opposed to normative considerations. This is largely because so many economists have internalized utilitarian theory or Pigou's modification of it. Determining whether policy X increase the extent of commerce (average or aggregate income) or not? is just another way of estimating whether policy X increases aggregate utility or not. If one accepts the utilitarian ethical framework, what matters is how a new policy or reforms affects outcomes, rather than some ethical feature of the policy itself. Thus, the policy analysis of the utilitarian school is substantially driven by advances in economic theory and new problems, rather than innovations in ethical theories per se. With respect to commerce, Pigou made it clear that utilitarian analysis implies that average income is an imperfect measure of aggregate utility (welfare), and that a commercial society may be improved through policies that do not increase income, as with policies to regulate externalities (environmental law), and intervention to reduce monopoly power (antitrust). He, and other utilitarians, would argue that the commercial society is made more attractive through such policies. A long series of such policies could be a source of growth in the relevant dimension (GNP or aggregate utility) even if the individual steps do not increase average income. On the other hand, if the policies are not motivated by utilitarian aims, as public choice theory suggests will be the case, a long series of such policies may reduce both aggregate utility and income. This debate among utilitarian economists produced many pages in academic journals and on the editorial pages of newspapers. The past few decades has witnessed a renewed interest in the many economically relevant effects of ethical beliefs on economic activities. This book is partly an effort to explore these effects more thoroughly or at least with a sharper line of analysis than in previous efforts. Although interest in the connection between ethics and economic development is by no means mainstream, as indicated by microeconomic and macroeconomic textbooks at both the graduate and undergraduate levels, there is evidence of a renewed interest in the interdependencies between ethics and economics. C. Ethics and Economic Development Within most societies, however, there is more variation in the ethical perspectives of individual than among mainstream Western economists, and so ethical differences play a larger role in the policy analysis of nonprofessionals. In democracies, such conclusions are decisive rather than the blackboard exercises of textbook welfare economics. Unless ethical dispositions are broadly supportive of market systems, public policies are likely to make commercial societies less productive and attractive, as when rent seeking or egalitarian interest determine policies rather than support for the material comfort, special forms of creativity, and lifestyles associated with commercial societies. Support for the latter, as indicated by part I of this volume, are substantially grounded in ethical and other normative beliefs about the good life. Chapter 12 has argued that ethical dispositions also affect the extent and speed of economic development through effects on the rate of innovation, adoption, and adjustment. In particular, a willingness to treat damages associated with innovation in a manner different from other areas of life is necessary. This is mostly likely to be the case when persons believe that page 14 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life economic innovations tend to generate progress, that is, systematic increases in the average quality of life. development. These effects create a secondary feedback from markets to the ethical theories of persons in the communities serviced by those markets. Without such substantially ethical conclusions, innovators would be disapprobated and punished rather than praised and rewarded. Public policies would tend to discourage or prohibit innovation, rather than support it. Insofar as innovation is an essential feature of a commercial society, it is clear that this is another area of economic life that benefits from ethical support, without which a dynamic commercial society is unlikely to emerge. To the extent it is possible to recognize ethical dispositions, consumers tend to reward firms that have internalized dispositions that improve the quality of their goods and services and reduce their costs. They will punish firms that fail to provide good service, sell faulty products, and make fraudulent claims about those products. D. Ethical Developments and the Emergence and Refinement of the Commercial Society Part I of this book demonstrated that many of the most influential philosophers in the West wrote on both ethical and economic topics, and many believed that commerce should play a role in a good life. How great a role varied among those whose ethical theories lent support to careers in commerce and virtues that tend to increase the productivity of individuals and teams in commercial enterprises. To the extent that the authors surveyed in Part I were or became mainstream during the period between 1500 and 1900, their analyses became increasingly supportive of commerce during this period. To the extent that this shift in outlook was commonplace, although not universal, it would have supported the gradual emergence of the commercial society through effects on work, cooperation, innovation, and public policy. As to the arrow of causality, if such exists, the claim of the present volume is that ethical theories and the extent to which they are internalized within a community is largely determined by non-economic factors but not entirely so. Philosophers and theologians rarely use markets as the primary source of their ethical and theological theories, although many find it useful to use commonplace economic activities to illustrate their theories. Partly with such effects in mind, firm owners (and the personnel departments of large firms) will attempt to identify persons with productivity-increasing dispositions, many of which are ethical in nature. Competition for such employees tends to increase the employment opportunities and salaries of persons who have internalized market-supporting ethical systems. These larger rewards, as well as the more frequent choice settings in which ethically relevant choices are made within firms and markets, tend to encourage the development of those market-supporting dispositions. The relationship between ethics and commerce is a boot-strapping process, rather than a unidirectional one. Nonetheless, the internalized ethics that exist at a point in time play a central role in societies that commercialize by allowing extended markets to develop, innovation to take place and by providing broader support for political institutions and public policies that help trading networks and economic organizations to flourish. Without these normative dispositions, it is likely that both the informal and formal rules of the game would inhibit or block innovation and commercialization, rather than to accept or promote them. Without ethical support, markets would still exist in every civil society, but they would be much smaller and much less productive. In that sense at least, the commercial society may be said to have moral foundations. As internalized norms that are supportive of commerce become more commonplace and more strongly internalized, new market opportunities emerge along with pressures for political reforms that support economic page 15 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life Inglehart, R. (1997) Modernization and Postmodernation: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. References Beugelsdijk, S. and T. van Schaik (2005) "Social capital and growth in European regions: An empirical test," European Journal of Political Economy 21: 301-24. Boettke, P. J. (2002) Calculation and Coordination: Essays on Socialism and Transitional Political Economy. London: Routledge. Buchanan, J. M. (1984) "Politics without romance," The Theory of Public Choice II. (Buchanan, J. M. and R. D. Tollison, Eds.) Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Hanusch, H. and A. Pyke (Eds.) (2007) Elgar Companion to NeoSchumpeterian Economics. Cheltenham UK: Edward Elgar. Hayek, F. A. (Ed.) (1935/2009) Collectivist Economic Planning: Critical Studies of the Possibilities of Socialism. Auburn Al.: Ludwig von Mises Institute. Hayek, F. A. [1968/2002], “Competition as a Discovery Process,” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 5: 9–23. Hayek, F. A. (1979) Law, Legislation, and Liberty, Vol. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Buchanan, J. M. and V. J. Vanberg (1991) "The Market as a Creative Process," Economics and Philosophy 7: 167-86. Kirzner, I. (1973) Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Bury, J. B. (1921/2011) The Idea of Progress: An Inquiry into Its Origin and Growth. London: Macmillan. Kindle Version from Public Domain Books. Knack, S. and P. Keefer (1997) "Does social capital have an economic payoff? Across-country investigation." Quarterly Journal of Economics 112: 1251-88. Cowen, T. and R. Fink (1985) "Inconsistent equilibrium constructs: the evenly rotating economy of Mises and Rothbard," American Economic Review 75: 866-69. Landa, J. (1994) Trust, Ethnicity, and Identity: Beyond the New Institutional Economics of Ethnic Trading Neworks, Contract Law, and Gift-Exchange. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Debreu, G. (1959) Theory of Value: An Axiomatic Analysis of Economic Equilibrium. New York: John Wiley and Sons (Cowles Foundation Monograph Series). Lavoie, D. (1985) Rivalry and Central Planning: The Socialist Calculation Debate Reconsidered. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lange, O., Taylor, F. M. and Lippincott, B. E. (1938) On the Economic Theory of Socialism. New York: McGraw-Hill. Güth, W. and H. Kliemt (1994) "Competition of cooperation: On the evolutionary economics of trust, exploitation, and moral attitudes," Metroeconomica 45: 155-87. Grossman, G. M. and Helpman, E. (1991) "Quality ladders in the theory of growth," Review of Economic Studies 58: 43-61. Lerner, A. (1934) “Economic Theory and Socialist Economy,” Review of Economic Studies 2: 51-61. Mill, J. S. (1959/2013) On Liberty. London: Parker and Sons. The Kindle Version is from John Stuart Mill, Complete Works, Minerva Classics. page 16 Ethics and the Commercial Society: Ch. 12 Economic Progress and Ethics: Commerce and the Better Life Moore, T. (1516 /1901/2012 ) Utopia. (The Kindle Version is from Public Domain Books, which is based on the 1919 Cassell and Company edition.) Pollitt, M. (2002) "The economics of trust, norms, and networks," Business Ethicss 11: 119-28. Rawls, J. (1999) A Theory of Justice, Revised Edition. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Romer, P. M. (1990) "Human capital and growth, Theory and evidence," Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 32: 251-86. Routledge, B. R. and J. von Amsberg (2003) "Social capital and growth," Journal of Monetary Economics 50: 167-193. Schumpeter, J. (1947/2012) Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, Second Edition. New York: Harper Row. Kindle Version from Start Publishing. Shackle, G. L. S. (1969) Decision, Order, and Time in Human Affairs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Solow, R. M. (1970) Growth Theory: An Exposition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Tinbergen (1964) Central Planning. New Haven: Yale University Press. Tabellini, G. (2010) "Culture and institutions: Economic development in the regions of Europe," Journal of the European Economic Association 8: 877-716. Temple, J. and P. A. Johnson (1998) "Social capability and economic growth," Quarterly Journal of Economics 113: 965-90. page 17