Ethical Foundations of the Commercial Society: Chapter 9

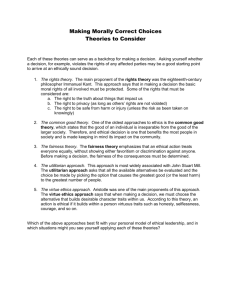

advertisement