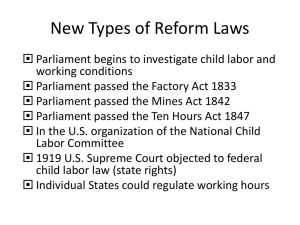

Perfecting Parliament : Liberalism, Constitutional Reform and the Rise of Western Democracy

advertisement