Assessing the New Federalism Recent Changes in Colorado Child Welfare Systems

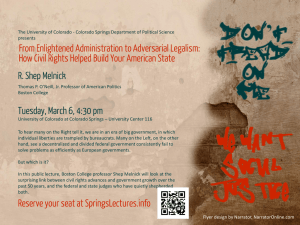

advertisement