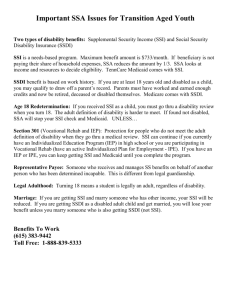

Policy Options for Assisting Child SSI Recipients in Transition

advertisement