Document 14881317

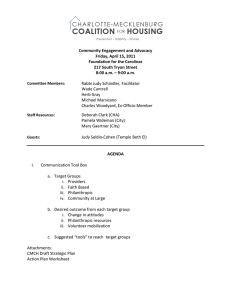

advertisement