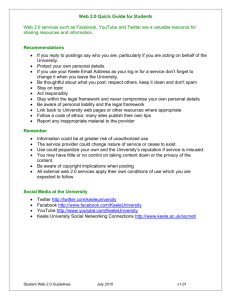

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SOCIAL STUDENT MEDIA:

advertisement