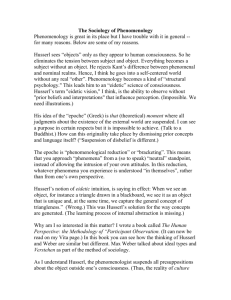

Ronald McIntyre and David Woodruff Smith, “Theory of Intentionality,” in... Husserl’s Phenomenology: A Textbook

advertisement