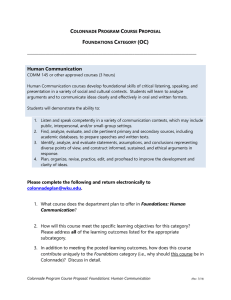

Colonnade General Education Committee Western Kentucky University

advertisement