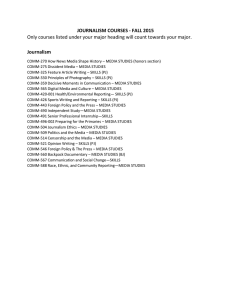

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE JOURNALISM THAT FACILITATES PUBLIC DISCOURSE AND ENGAGEMENT:

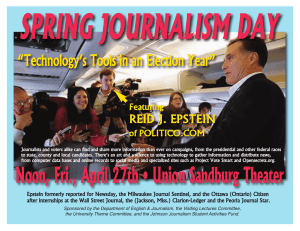

advertisement