Evaluation of the San Mateo County Children’s Health Initiative:

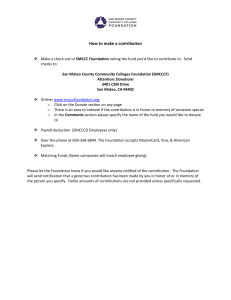

advertisement