Toward an Automated Reference Information S stem: Inmagic and the UCLA Read

advertisement

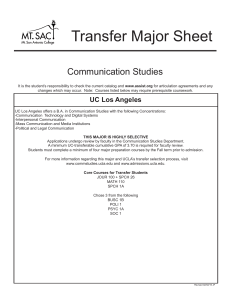

517 Toward an Automated Reference Information Sy stem: Inmagic and the UCLA Ready-Reference Information Files T he reference information files at several UCLA libraries we re merged and prepared for conversion to machinereadable form under a Council on Library Resources gra~lt . The database structure was conceived using the followmg factors : data elements, fi eld indexes, syndetic structure, and the possible future sharing of files with the Los A~geles Public Library . Information was entered into a microcomputer using Inmagic , a sophisticated text management sy tern that includes among its features Boolean searching, extensive indexing capabilities, and variablelength fields. Future implementation of Infofile will depend on funding, but may include translation into ORION, the UCLA online catalog. Mark Stover and Esther Grassian tark Stover is Automation Project M anager and Theological Librarian, Calvin College and ia rn~ary Library, Grand R apids , Michigan . Esther Grassian is Reference/Instruction Librarlion,J CLA, California . Submitted fo r review August 15 , 1988; revised and accepted for publican anua ry I 7, 1989 . A. en n ~ndispensible source for many referih ce librarians is an unassuming ftle of three-by-five-inch cards called variously re; reference information file , the readyfererence ftle, or the information and rein ra] file. It is a valuable tool , often comst g to the rescue in situations where anandard sources do not seem to have the so Slv~r. Diana Thomas describes the raind etre of the reference information file: 'J::onaareference l£bran·an spends any length of quest£on for wh£ch there £s no obvious 1 10 10 urce to Provide an answer, it is often a good idea If lllak~ ~n information note or card on the subject. 1~Pecifi~ subject head£ngs are establishedfor such 11~Tnzatzon (i. e. , an authon·ty fi"Le), consid~ab~e a.rke can be saved the next time the questzon zs ar hd. · · . Elus£ve quotations, the names of the buc~ects who des£gned the library and other local 1 lllgs, and the existence ofa bibliography on a certain subject in an issue of ajournal are examples of items which can be usefully incorporated into an information file. ' Can discrete reference information ftles be automated and merged so as to bring about a higher quality of service? O nline catalogs are of great benefit to the reference librarian, both as aids in finding materials in the library and as teaching tools. Online ready-reference searching, too, has been of benefit to reference librarians, especially for fact finding and citation verification. Mediated searching, on the other hand, has actually transferred the work of the end-user (searching manual indexes) 2 to the librarian. Certain tools, such as online catalogs and commercial databases on CD-R OM , have been directed toward end users. In many cases, reference librarians have been 518 SUMMER 1989 RQ intimately involved in the creation of these databases, and have offered valuable input as to their content, command structure, and display formats. However, we know of few databases created by reference librarians for the use of reference librarians. Infofile is just such a database , created locally through the lnmagic software. Automation of ready-reference information files is a positive step for the reference librarian who wishes to take advantage of current technology . Information files are generally useful resources for reference librarians. We believe that they become even more useful when they are converted to 3 machine-readable form . Yet, very little work on this topic has been published . We hope to provide in this article a model or prototype for other libraries who may wish to automate their information and referral files . LITERATURE REVIEW Several articles have been written about lnmagic. Some of these are review articles,• and some are "how-l-automatedmy-library-good " type of articles.' lnmagic has received very good reviews in the literature, although its limitations are often emphasized. None of the articles dealing with specific projects using Inmagic utilized the program as a ready-reference information file, although similar concepts were sometimes discussed. The literature does not contain a great deal about reference information files . 6 Thomas comments positively on the nature of manual information and referral files, but does not go into detail. We were able to discover in the literature two different projects dealing with automated ready7 reference files. The first , "Linkline, " is a relatively small system that was developed at Freeman Hospital in Joplin, Missouri, but due to financial factors is now part of the Joplin Public Library Reference Department. It runs on a Macintosh microcomputer with a 10-megabyte hard drive using the Main Street Filer software . Each of the records in the 2,500-record database can be accessed by a key index term, a secondary index term, date of input, county , and city. Boolean logic is restricted to ''an ding'' together the primary keyword and the secondary keyword. All the fields are fixed-length, and Linkline operators must be well-versed in the Linkline indexing system. The database contains mostly medical information, but also includes local and national data on civic and charitable organizations, government agencies, and various support groups. The second automated reference information and referral system that we found in the literature is called ''Maggie's 8 Place. " Available through the Pike's Peak Library System, Maggie's Place is a community information file that runs on a PDP minicomputer. Together with the library system's online catalog, it is accessible by the end-user either at the library or from their home (if they own a microcomputer and modem). The flies provide access to information related to local events, organizations, clubs, and educational programs. It also includes many other community concerns such as health care and welfare services. Both of the above systems continue to be used successfully by reference librarians. The lack of information on automated ready-reference systems in the literature does not mean that other such systems do not exist. Undoubtedly similar projects have been undertaken (as, for example, the project now under way at the Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL) to automate their extensive collection of reference information files). What it does mean, however, is that there is a great deal of room for creative thought and effort in this area. The literature on subject access and authority control is rich and extensive , and the advent of automated library flies has not dulled the minds of those who write 9 about such things. It goes beyond the scope of this study to cover the entire spectrum of research that has been done (and continues to proliferate) in this area. However, certain concepts need to be understood if the reader is to grasp the problematic nature of developing subject access and authority control for an automated ready-reference information file. Therefore, occasionally different ideas will be re· ferred to that have surfaced in the litera· ture so as to provide a basic (though by nc means exhaustive) foundation for th i: study. HISTORY AND BACKGROUND The idea _of developing a machin e AUTOMATED REFERENCE INFORMATION SYSTEM readable reference information file at UC LA dates back to 1980, when a student at the UCLA Graduate School of Library and Information Science attempted to automate the UCLA College (undergraduate) Library reference information file. The experiment failed, primarily because of severe hardware and software limitations. In 1986, Esther Grassian revived the idea and began to investigate the different possibilities in ready-reference automation. She realized that an online information flle had ramifications far beyond the confines of the College Library. With the help of Nancy Burns-McConnohie , a UCLA Graduate School of Library and Information Science intern, she sought to create a merged UCLA reference flle (containing records from the information flles of different UCLA libraries) that would be hospitable to other reference information files imported from libraries outside of UCLA. After deciding on Inmagic, Grassian began to seek funding for the project. " UC LA Infofile" was eventually designed and built using funds from a Coun10 cil on Library Resources grant. Three other libraries at UCLA agreed to take part in the project," and a tentative agreement was made with the Los Angeles Public Library to share data experimentally. As Grassian's research assistant during 1987 and 1988, Mark Stover was responsible fo r assisting her in the file-building aspect of the project. This included (among other things) assistance in the design of the data structure, development of an entry format and opening screen, and input of the ftl.es into Inmagic. The manual reference information flles at UC LA have been in existence for many years. Each library' s flle contains information that , for the most part, is unique to that library. As would be expected, each file reflects the interests and needs of that library' s users. The UCLA information files are quite extensive in scope. The flle at the College Library contains about 1,000 cards. The cards are often useful in pro~iding a questioner with quick information (whether factual or referral in natu~e). A reference librarian in each library Ism charge of each flle and updates it on an ad hoc basis, although new information often comes from other librarians who feel that a particular piece of information or 519 the answer to a particular question should be placed in the information file. The UCLA ready-reference flles contain (but are not limited to) the following categories of records: 1. Associations. The record explains what the association is, what it does, and it usually gives the address and phone number of the association (e.g., AFSCME). 2. UCLA special collections. Although not exhaustive, many records in the ready-reference flles describe a special collection held by the UCLA Library: what it is, where it is located, and when it was received (e. g. , Asian American Collection). 3 . How to do something on campus (e.g., audio tape copying). 4. How to find information on miscellaneous subjects (e .g., banks, stocks, and bonds). 5 . Historical and directional information for different sites on campus (e .g. , Boelter Hall). 6. UCLA rules or policies (e.g. , bicycles and mopeds). 7. Bibliographical information on a subject. 8. Full texts of speeches or songs (e.g., John F. Kennedy's inaugural address). 9. Off-campus library information (e.g., Braille Institute of America Library) . 10. Definitions of terms (e.g. , brieflisted), acronyms (e .g. , CLU), and phrases. 11 . Biographical information on persons historically related to UCLA (e.g., Robert Vosper) . HARDWARE AND SOFTWARE CONSIDERATIONS An IBM PC-XT microcomputer was selected for this project for two reasons . First , the installation base of these machines (and their clones) is so large that hardware or compatible software obsolescence is unlikely for the near future . Second, the software chosen for this project (Inmagic) runs only on the MS-DOS operating system , and MS-DOS was designed for use with IBM PCs or compatibles. A hard drive was not absolutely necessary, but it was important if we were to use Inmagic effectively with a large database and maintain a respectable response time nee- 520 SUMMER 1989 RQ essary for ready-reference use. Inmagic, a powerful text management system, was chosen for this project for several reasons. First, it allows for a virtually unlimited number of characters in each field. This was important to us because UCLA's files contain a great deal of textual information. This effectively eliminated many database management systems (like dBase III + ), but made Inmagic a prime contender. Second , Inmagic's data structure is quite flexible, and allows for multiple repeating fields . This was attractive to us, since added entries are often necessary in Infoflle. Third, Inmagic can import and export data files written in ASCII. This capability would be necessary if sharing information with other libraries (such as the Los Angeles Public Library) was ever desired or if uploading of the Infofile database into ORION (UCLA's online catalog) were to take place. Fourth, Inmagic is relatively easy to use, whether in the design of the data structure, formatting reports, inputting new data , or searching the database . Beiser states: While a few general-purpose database managers can be set up to emulate some of lnmagic's capabilities, none of them comes close to offering the combination of simplicity, searching s;eed, and flexibility in text storage and retrieval. One major drawback that Inmagic has is its nearly prohibitive price tag ($975 at the writing of this article). " Fortunately, we were able to begin the project through the support of Dean Robert M. Hayes of the UCLA Graduate School of Library and Information Science. •• However, fmancial restrictions may hinder future implementation oflnfoflle (through the use oflnmagic) if additional funding is not obtained. USING INMAGIC Inmagic is not a database management system. It is a text management system with sophisticated searching capabilities and variable-length fields. However, it does not allow the user to open more than one file at a time, thus setting itself apart from most database management systems. Inmagic is menu-driven up until the us~r is actually ready to search for data. Th1s makes it quite easy to use . Search commands must be used (and a relatively sim- ple command language must be learned) to perform searches, but this enhances Inmagic's power. Inmagic is designed to be used with a 300-page manual . The manual is clear and concise, although the index is rather sparse and not particularly helpful. The manual is divided into six major sections. "Select" teaches the user the various search commands and functions. Boolean operators may be used in a search so that one or m ore terms can be searched in one or m ore fields . Searches can be stored and/or repeated, and search results can be displayed, printed, or written to disk in a wide variety of report formats. Using " Select" one can show the keys in the index show a disk directory (without going back to DOS), or view an online tutorial. Inmagic also provides keyword searching, exact matches, or truncation using several relational operators. "Editor" gives an overview of Inma· gic' s full-screen editing capabilities. Many of the functions that one finds in a word processing program are also found in In· magic. One can find and highlight text, cut and paste, and delete and insert. One can also move around the screen with ease using the cursor, the backspace key , there· turn key, or the home and end keys. Using " Maintain " records can be created or changed with the editor, or added in batch mode using an imported ASCII file. ' ' De· fme" allows the user to build a data struc· ture, set up flle specifications, and design report formats. It also explains the differ· ent indexing and sorting functions that In· magic provides. " Report " describes the fairly sophisti· cated report formats that Inmagic allows. Adding text (or punctuation) to a report, positioning text anywhere on the page (or screen), using columns instead of rows and restricting reports to certain fields o; subfields are just a few of the ways that In· magic allows the user to manipulate data in output form. "Auxiliary" lets the user print a list of index entries for a particular field, as well as write the database to an ASCII file. The manual also gives instruc· tions on backup procedures, database re· covery, system errors, and internal errors. DATABASE DESIGN Jessica Milstead states, "Ev er~ AUTOMATED REFERENCE INFORMATION SYSTEM choice-and designing any system involves a set of choices-limits other choices, and it behooves the designer to be well aware of the impact of such decisions. " " We knew before we started the project that some of our choices would be difficult ones, and that any decisions we made would be restrictive to one degree or another. The decision-making process was not magical or spontaneous, and iteration played a key role in the choices that we made. We tried to base our decisions on well-established subject access theory, yet , even so, inconsistencies and flaws (some of which will only be discovered after implementation) remain in the system. Certain concepts in cataloging theory have relevance when brought to bear on an automated reference information ftle system. In terms of subject access, for example, the information flle should probably reproduce the two primary functions of a catalog: to help the user find specific information when the subject is known , and to show what information can be found un~er a certain topic. However , since very httle of the Infoftle database contains bibliographic information, rules or concepts taken from subject cataloging may not always be relevant. Data Elements I?foflle's data structure was originally d1v1ded into two broad categories: bibliographic data elements and nonbibliographic data elements. The nonbibliographic data make up the bulk oflnfofiJ.e ' s contents. The bibliographic data fields were added to Infoftle's data structure for three reasons : to facilitate sharing with 16 LAPL's information files (which contain 1llb. ~Y bibliographic citations); to provide 1 ~hographic access to InfofiJ.e; and to faCilitate and enhance a possible future ganslation of Infoftle from Inmagic into RION . To create a more hospitable search environment, the bibliographic ~ata was at first repeated in the Abstract Ield (since most searching is done on ei~er the Subject field or the Abstract field). 0 ~ever, we eventually realized that re(leat.mg bibliographic information was essentially a duplication of effort, and was n~t necessary for effective implementation fn~the da~aba.~e . At present, bibliographic 0 fffiation 1s only entered into the Ab- 521 stract, and is not entered into any of the bibliographic fields. The fields are, however, retained in the data structure so as to facilitate the possible importation of bibliographic data into lnfofiJ.e in the future. As librarians, we had overemphasized the importance of bibliographic data in reference information ftles. lnfofile, however, is primarily a nonbibliographic database, and any bibliographic information that is found in it is only incidental to its purpose and effectiveness. lnfofiJ.e's data structure (see figure 1) closely follows the data structure used in the Reference Automation Project at LAPL. The unique identifier for each InfofiJ.e record is called the Record Number, and is assigned a code based on the library 17 of origination. This is the only required field in lnfoflle. The bibliographic fields follow the Record Number, and are all found in the top half of Infoflle' s record template. Following the bibliographic fields is one of InfofiJ.e's most important data elements, the Subject field. This field uses Library of Congress Subject Headings (and some non-LCSH headings) to describe the subject matter of each record . The Subject field attempts to be complete (but not exhaustive) in indexing Infoftle with controlled vocabulary . Next is the Geographic Code, which is used if the geographic aspect of the information is imporRECORD NUMBER _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ AUTHOR/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ AUTHORARTICLE/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ __ TITLE/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ JOURNAU1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ PUBLISHER/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ PAGES/1 ______________ DATE/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ CALL NUMBER/1 - - - - - - - - LOCATION/1 ____________ SUBJECT/1 - - - - - - - - - - GEOCODE/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ LANGUAGE/1 _____ _ _ _ _ _ __ ABSTRACT/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ ILLUSTRATION/1- - - - - - - - SOURCE/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ VALIDATION DATE/1 _ _ _ _ _ _ __ LAST UPDATE/1 - - - - - - - - - - Fig. 1. Data Structure. 522 SUMMER 1989 RQ tant. The Language field is used if a language other than English is related to the record . This is followed by the Abstract field . The Abstract is the heart of Infofile, containing the bulk of the information found in each record . Following the Abstract is the Illustration field . If the information is highly pictorial, or indicates where an illustration may be obtained, appropriate notes are to be made here. Next is the Source field, which indicates the source of the information . The Validation Date field is used to indicate the frequency with which the information should be checked to see if it is still valid. The two most commonly used codes for this "tickler field' ' are A (for annual updates) and N (for no updates). With this field it is possible to produce a printout of records which need to be checked on a regular basis. The final data element in lnfofile is the Last Update. This field contains the last date updated and the initials of the updater. Indexes One of the most radical ways in which computers have improved access to information is the way in which items are in18 dexed. lnmagic is capable of indexing every word of every field of every record in Infofile. This is not optimal, however, because certain fields would be unnecessarily indexed, thus taking up valuable disk space. Which fields , then, should be indexed? 19 After careful consideration we decided to index the following fields : Subject, Abstract, Record Number, Geographic Code, Language , Last Update, and Author. Of these , the Subject and Abstract field indexes are the most important, since they most often provide the user with index terms relevant enough to give access to the appropriate record(s) . Although somewhat of an oversimplification, it is fair to say that there are essentially two types of indexing methods . Derived indexing (or use of uncontrolled vocabulary) takes terms from the actual record. Assigned indexing (or use of controlled vocabulary) provides index terms 20 from an outside source. lnfofile uses both m ethods, since the Subject field consists of assigned index terms while the Abstract field consists of derived index terms . Using both types of indexing methods provides the user with a valuable choice: if search- ing on derived index terms is unhelpful, one can try searching on assigned index terms. Similarly, if searching on uncontrolled vocabulary yields too many records, one can try searching on controlled vocabulary for more precise results. Precision/recall problems in larger files have long plagued the online searcher. Having a choice between derived and assigned terms (as well as having the capability for Boolean operations) may alleviate some of these problems in lnfoflle . Syndetics Syndetic structure generally refers to the way in which cross-references are employed to help the user search a system indexed with controlled vocabulary. 21 Crossreferences may be divided into essentially two categories: prescriptive (or "See") references, and permissive (or "See also") 22 references . We are primarily concerned ~ith prescriptive references in this discussion . Milstead has addressed the problematic nature of cross-references and has concluded that desi~ing a syndetic structure 23 is a difficult task. Despite this, we were confident that lnmagic offered the capabilities that would enable us to successfully transfer the syndetic structure of our manual information files to an automated systern. lnfofile uses added subject entries to simulate "See" references. Usually, a valid L.C. heading is placed in the primary Subject field . Added Subject fields will often contain L.C. "See" references, other valid L.C . subject headings and non-L.C. subject headings (usually ~rans­ planted from the manual environment of the information file). This type of subject access accentuates the difficulty of transferring the syndetic structure of LC SH into an automated process. However, this system does allow access to the record through multiple subject terms, including " See" references. All cross-references are transparent to the user, since the main subject heading is the only subject entry visible on the screen display. An alte native procedure would have been to produce "dummy" records containing nothing but a "See" reference (simulating th manual environment) , but this woul have created a " two-step lookup" proces 1 AUTOMATED REFERENCE INFORMATION SYSTEM as well as wasting disk space. Milstead speaks of the development of ''automatic cross-referencing systems which switch automatically or semiautomatically from the user's entry term to the 2 equivalent used in the system. " • lnfoflle contains just such a system where the user is " automatically" or "transparently" brought from his or her search term to the valid subject heading and attached record. Milstead sees a day when the conceptual parameters of syndetic structures and access points will become less defined (and therefore more "fuzzy") in the minds of 25 both users and system designers . This is exactly what is happening in lnfofile. Within the automated environment, Infofile has merged the concepts of syndetic structure and access points to fit its specific needs . In this way it has changed the nature and character of syndetics as it was previously defined in the manual environment. FILE BUILDING The file building stage of the Infoflle project was essentially a retrospective conversion (recon) project, with all of the attendant difficulties that are often associated with the retrospective conversion of library catalogs. However, too much should not be made of the similarities between these two types of projects, since library catalog recon is undeniably a much more complex and time-consuming process than the conversion of reference information files to machine-readable form . Entering the Data In general, entering data into Infoflle was fairly straightforward. We first went through the manual information flle and determined the primary headings and added entries. Then we entered data directly from three-by-five-inch cards into 26 lnmagic. After each session a backup was made of the database in case lnfofile should ever be accidentally damaged. One of the problems that we faced in this pr_oject was the "dirty record syndrome. " Dirty records can be caused by several factors. First, they can come as a result of typographical errors by the person entering the data. Second, they can come as a result of problems in the manual flies. These were either typographical errors, misspell- 523 ings, or factual errors (usually caused by the manual cards not having been updated). Typographical errors and misspellings are fairly easy to catch and correct. Factual errors, on the other hand, are much harder to clean up, since it would consume a prohibitive amount of time to research and update the entire manual information flle. This problem accentuates the need for a regular and systematic method for updating reference information files . A third cause of dirty records in lnfoflle stems from a unique characteristic in Inmagic . lnmagic does not like any space to be wasted, and if it sees any unaccountedfor empty space, it deletes it. This is called ''space compacting'' and, admirable though it may be from a disk capacity perspective, it caused us a slight problem . With its reports format, Inmagic can place information from any field anywhere on the screen. However, it cannot format in a special way the information within a certain field . We, on the other hand, desired a minimal number of "special effects" for the Abstract field. We wanted to have paragraph separation capability, and for certain records we wanted to place different kinds of information on separate lines. After some frustrating experimentation (and a call to lnmagic support) we decided to use added entries in the Abstract field to create the illusion of paragraph separation. For example, if a new paragraph or new line is necessary, one simply hits FlO to create an added field . In the report format , this appears as a new paragraph (or new line) , since field names or labels do not show up on the display screen. It is not a pretty solution to the problem, but it works . All of the manual information flle entries were already labeled with subject headings before we began this project. However, many of these headings were not valid Library of Congress headings , and had to be recataloged . Thus, part of the retrospective conversion process involved comparing the subject headings with LCSH and producing new or added subject entries when appropriate . Report Formats lnfofile provides the user with two choices of report formats (as well as the de- 524 SUMMER 1989 RQ fault report format) . The VIEW format is designed for use with viewing screen displays of search results. It is limited to one record per screen, and attempts to display the record information in a clear, yet efficient way. The VIEW format will display the Subject, Abstract, Source, Last Update, and Record Number fields, with the Subject entries displayed in all capital letters and the Abstract field indented to facilitate viewing the record . The second format, PRINT, is designed to print out search results (or the entire file, if desired) . It is identical to VIEW, except that it does not limit each page to one record . The current date , the page number, and the words "INFOFILE: The UCLA Reference Information System '' appear at the top of each page . If the user wants to see fields that are not part of the report format , he or she can display or print the search results using the default format. This will list all of the fields , along with the field names and field labels. Searching lnfofile Infofile is a full-text database that has the advantage of being a "single-lookup" file . Concerning this type of file Milstead states, ''Once the user locates an entry, the information is all there and there is no need to look elsewhere for the document.' ' 27 The positive aspects of a singlelookup file are, however , balanced against the disadvantage of being expensive to create, index , and store. Also, it should be noted that although Infofile is primarily "one-step lookup" in nature, several records refer the user to a second source of information (such as monographs or pamphlet files) . The Infofile database can be searched using a variety of Boolean and relational operators. The basic retrieval command in Inmagic, ' ' Get ,' ' can be used for simple or complex searches. For example, '' Get subject = computers'' will retrieve all of the records where one of the Subject fields consists of the word "computers." A different approach might be to broaden the search strategy to include all records where the word "computers" is contained in the Subject field : "G su cw computers" (where g stands for "get," su stands for "subject," and cw stands for "contains word " ). Truncation is also possible, so that "G su cs com put" will pull up all the records where the Subject field contains the stem "com put." Thus, "computer," "computers," "computing," etc. will all be included. Inmagic supports phrase searching, so that "G su = 'computer science' " will retrieve all the records that use this phrase as a subject heading. Boolean logic h elps the user to broaden a search to more than one field or more than one search term . Thus, "G su/ab cw 'computerized' or 'automated' " will bring up all the records that contain either the word "computerized" or the word "automated" in either the Subject field or the Abstract field . Of course , other Boolean operators like "and" or "not" can be used to limit or qualify a search. Fields other than Subject and Abstract can be searched for various reasons . The Last Update field may be scanned to retrieve all the records that have not been updated for x number of years. The G eographic Code field or the Language field can be searched to find records dealing with a certain geographic area or language . The Record Number field may be searched to determine how many records originated in a particular campus library. After Infoflle completes its search of the database, the user can display the results using three different formats . "Display" will display the results using the default format . ''Disp_lay using view' ' will display the results usmg the VIEW format discussed above, and "Print using print" will create a printout of the results (see figure 2). Searching Infoflle is not always successful. The major problem continues to be in the areas of precision and recall. M any searches in Infofile, especially those performed on the Abstract field, will yield a number of false drops. Subject searches are more precise, but even there the number offalse drops can be troublesome . One possible solution is to search only the Subject ·field with controlled vocabulary . This will lower the recall, but it makes search results much more precise. If a Subject search is unsatisfactory, an Abstract search may then be appropriate . Combined Subject/Abstract searches may be called for if the user wishes to retrieve the largest number of search results possible. AUTOMATED REFERENCE INFORMATION SYSTEM 525 lNFOFILE : The UCLA Reference Informa tion System 4/21/88 NITKA QOHN C .) COLLECTION The John C. Nitka Collection con ta ins books and periodical issues of science fi ction and fantasy. (6, 000 volumes plus la rge collection of pulps) . R ece ived : Au gust 1967-purchase Location : Special C ollec tions CL254 HARVARD REPORT The tex t of the report , " Federal Res trictions on the Free Flow of A cade~i c lll:formation Ideas ," prepared by John Shattuck, a vice- president at Harva rd , is ava1lable m the Jan. 9, 1985 iss ue of Chronicle of H igher Education, beginning on p . 13 and is ava1lable on microfi che. Jan '85 CB EP153 BLAC K NATIONAL ANTHEM Althou gh this is commonly known as the Black National Anth ~ m , th~ actu al title is " ~ift Every Voice and Sing,'' by J ames W eldon Johnson . The Iyn es are m the Afro-Amencan Almanac on p.145 a nd in the Negro Almanac on p . 164. CL44 Fig. 2. " Print" Report Format. Authority File The Library of Congress Subject Heading list is used as Infoftle' s primary subject authority ftle . However, Infoflle occasionally uses a non-LCSH heading as the main subject entry in a record . LCSH has been criticized as awkward and inconsistent, as not appropriate for the online environment, and as a poor substi28 tute fo r a thesaurus . Why, then , was LCSH chosen as our subject authority file? First, it is in many ways a de facto standard. Second, librarians (who will in fact be the ones to use Infoftle) are familiar with LCSH, and will not have to learn a new vocabulary to use it. Third , the project did not provide the time that would be needed to design and build a thesaurus specifically geared toward Infoftle. What we needed was an established authority file, and LCSH provided the answer. Fourth, LCSH was the vocabulary of choice for LAPL, and since we hope to eventually share data with them, LCSH seemed an appropriate choice for us as well . FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS We hope that in the near future we will see the full implementation of Infoflle. Implementation may take one of three forms . The first form (approved and currently under way) involves printing out Infof~e in its entirety and giving a copy of this merged ftle to each librar;; .i nvolved in ~e project. This' 'hard cop">: IS accompanied by a printed index of subject.t~rms ( mcluding '' See'' references) to facilitate access to the ftle . Also, printouts of each new record added to the database can be distributed rather easily. Printing out Infoftle is not ideal in terms of what it was designed to do but until the project receives more fu~ding or is approved for co~version to ORION, it is the only alternatiVe. . The second form of implementation would involve using a machine-readable copy of Infoftle at the reference desks ~f each library involved in the project. .T.lus is, of course, contingent upon rece1v:mg funding for hardware (a PC or compatible with a twenty megabyte hard dnve for each reference desk) and software (a copy oflnmagic for each site). . The third form of implementation would involve the translation of the Infoftle database from Inmagic into ORION, UCLA's online catalog. The implications of such a possibility make it id~al for t~o reasons. First, running on a mamframe mstead of a microcomputer would considerably heighten the speed of Infoflle . Second, the problem of needing to have a 526 SUMMER 1989 RQ microcomputer with a hard drive and a copy of Inmagic at each reference desk would be solved, since ORION terminals already exist at the reference desks of each library at UCLA. While not a difficult task, conversion to ORION has not yet received administrative approval. If and when Infofile is finally implemented in a machine-readable environment, it will be necessary to test and evaluate it . The methods of evaluation have not yet been determined, but they would undoubtedly involve such factors as response time, down time, false drops , poor recall, amount of use , and " user-friendliness . " Surveys and tally sheets would be the primary media used to gather data. At the outset of this project one of the goals of the lnfofile project was to share data with the Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL) by exchanging floppy disks annually or semiannually yet maintaining discrete sets of files. A further long-range goal of this project was to obtain administrative approval from both LAPL and UCLA to create a merged UCLA/LAPL megainformation file on ORION. Because of the fires at LAPL and the need for administrative consideration and approval, the date that this cooperative effort might begin is unknown . However, the extent and quality of the LAPL files and indexes makes implementation of this aspect of the project highly desirable. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS UCLA reference information files into on e machine-readable file was not an e asy task . The literature did not contain much on the subject, and financial considerations placed many obstacles in our path. Choosing Inmagic proved to be a wise decision, as it seemed (for the most part) that this software was designed for just such a project. The construction of a data structure and the choice of data elements and field indexes provided us with an education in database design , especially in the area of syndetics. The bulk of the project, including d atabase design and rue building, has b een completed. However , future developments, including the actual implementation of InfofUe at UCLA reference d esks, are still on the horizon. Once InfofUe has been implemented at UCLA , we believe that with careful, joint multi-type library planning, the potential also exists for a vast combined community information and referral rue. The success of this project remains to be seen . However, even if future testing and evaluation show InfofUe to be a failure, it will not have been in vain . Reference librarians must continue to experiment with new technologies. It is especially within the domain of microcomputers that the greatest potential lies for the reference librarian. Only by creative, innovative, and experimental activity will we ever unleash the power of this incredible desktop rna· chine. •• The conversion of the four distinct NOTES AND REFERENCES 1. Diana Thomas, Ann T . Hinckl ey, and Elizabeth R. Eisenbach , The Effective Reference Librarian (O rlando , Flori da : Academic P r., Inc .), p.19-20 . 2. H arry M . K riz and Victoria T. Kok, " The Computerized R eference Depa rtment: Buyi ng the Future,' ' RQ 25: 199 (Wi nte r 1985 ). 3 . Lois M ai C han (i n Pauline A. Cochrane, ed . , Improving LCSH f or Use in Online Catalogs (Littl e· ton, Colorado: Li b raries Unlim ited , Inc., 1986), p . l 23-33) has delineated fiv e ways in which onli ne subject access is superior to manual subject access . ( I) K eyword or component word search (including truncation). T his overcomes the limita tions of the linear approach of man· ual systems, where access can only be found through the entry word . (2) Boolean operations. (3) Limiting or qualifying . (4) Synonym operati on (hidden "see'' references) . (5) Onl ine the· saurus display . 4. See especiall y Karl Beiser, " Inmagic, " Library Software Review 4:229-35 Ouly-Au g. 1985), and " lnmagic R evisited , " Wilson L ibrary Bulletin 62: 103 Oune 1988). See also R ao Alu ri. " In magic," Information Technology and L ibraries 7:212- 14 Oune 1988), and Gerald Lu nd een a nd Carol Tenopir, " Microcomputer Software for In-House Databases: Four T op Package! U nder $2000, " Online 9:30-38 (Sept. 1985). 5. See Geo rge L. C urran , ' ' Inmagic: Kudos and Caveats, '' Databa_se 9 :38- 40 (Dec. 1986) . Alsc AUTOMATED REFERENCE INFORMATION SYSTEM 527 see Helen P. Burwell, "Inmagic in Practice: Version 7 in a Law Library," Database9:31-36 (Dec. 1986). 6. Thomas , p.19-20 . 7. Jean A. Blackwood, "Library Linkline," Show-Me Libraries 36:28-3 1 (Aug. 1985). 8. Kenneth E. Dowlin and Barbara Conroy, "The Online Community Resource Files at the Pikes Peak Library," Program 19:140-49 (Apr. 1985). See also Carol E. Emmens, "About Maggie's Place," School Library journal29 :53 (Sept . 1982). A more recent view of this system can be found in Nina Alexis Malyshev, "Concept and R eality : Managing Pike's Peak Library District's Community Resource and Information System," Reference Services Review 16( 4 ): 7-12 ( 1988). 9. See jessica L. Milstead, Subject Access Systems (Orlando, Florida: Academic Pr., Inc ., 1984) for an excellent overview and analysis of the current "state-of-the-art." 10. The principal awardee of this grant was Dean Robert M. Hayes, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, UCLA. II. The UCLA Art Library, the UCLA Education/Psychology Library, and the UCLA Public Affairs Service . 12. Beiser, "Inmagic," p .235. 13. lnmagic gives substantial discounts for purchase of multiple co pies of the program . 14. Dean Hayes a llowed us to use the GSLIS copy of Inmagic for the filebuilding stage of the project. 15. Milstead, p. ix. 16. In preliminary discussion, LAPL agreed to let us use their data structure . As we had hoped to merge and/or exchange files with LAPL at some point, we designed our data structure to match theirs closely. 17 . E. g., the twentieth record entered from College Library's file was assigned the Record Numbe r "CL20." 18. Milstead, p .39 . 19. Ibid., p.88-93, for a discussion of the various issues involved in determining which data elements in the record should receive indexing. 20. Ibid., p.103-153. 21. For a description of the development and maintenance of a syndetic structure, Ibid ., p .67-82. 22. Ibid ., p. 70. 23. Ibid . , p.81. 24. Ibid . , p .80. 25. Ibid . , p.82. She states that "new developments in computer-aided indexing are making it possible to envision broadening the entry vocabulary concept to the point where the difference be tween index terms and syndetic structure effectively becomes transparent to the users." 26. Inmagic allows the user to create records using one of two methods. One can either input records directly into Inmagic (as we chose to do), or one can create the records in an outside ASCII fil e and later import them into In magic. The latter method solves the problem, a major one if the database (or the individual record) is large, of having to wait anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes for Inmagic to save and index each record that is created. If the ASCII file is loaded "batchstyle" in lnmagic, one can complete the process overnight. As lnfofile becomes larger (its present size is about I ,000 records), we may have to consider using this second method . 27 . Ibid ., p . 18 . 28. For a thorough analysis of the issues involved , as well as insightful essays by leading authori-' ties, see Pauline A . Cochrane, ed., Improving LCSHjor Use in Online Catalogs (Littleton, Colorado: Libraries Unlimited , Inc. , 1986) . Also see Mary Dykstra, ' 'LC Subject Headings Disguised as a Thesaurus ," Library journal 113 :42-46 (Mar. I, 1988) for a sharp critique of LCSH .