Formative Report on the DC 21 Century Community Learning Center

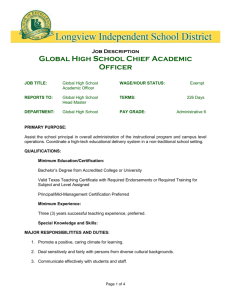

advertisement