PROVIDING MEDICAID TO YOUTH FORMERLY IN FOSTER CARE UNDER THE CHAFEE OPTION:

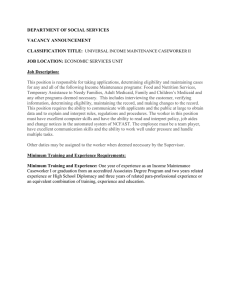

advertisement