1999 Report: Violence Against Women Act of 1994 Evaluation of the

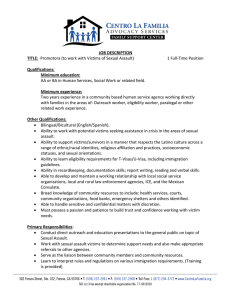

advertisement