Document 14838060

advertisement

EMPLOYER’S RIGHTS AND CONTRACTOR’S LIABILITIES IN RELATION TO

CONSTRUCTION DEFECTS AFTER FINAL CERTIFICATE

TAN PEI LING

UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MALAYSIA

DEDICATION

To my beloved father, mother,

sister and Chee Siong

Thank you for your support, guidance and everything.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This master project can be completed successfully due to the contribution of

many people. First of all, I would like to express my highest gratitude to my

supervisor, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Maizon Hashim for her patience, guidance, advice and

support in order to complete this master project.

Next, I would like to thank all the lecturers for the course of Master of

Science (Construction Contract Management), for their patience and kind advice

during the process of completing the master project.

Besides that, I am deeply grateful to my family for their unconditional love

and care through out the years. Unforgettable, I would like to thank Chee Siong who

has given me full support during this study.

Not forgetting my classmates, a token of appreciation goes to them for giving

lots of advice on how to complete and write this project.

ABSTRACT

Most of the standard forms of contract contain provisions dealing with

defective works. Defective works could be in the forms of design fault, defective

building materials or bad workmanships. Any defects, shrinkages or other faults

arising during construction and defects liability period due to defective materials or

workmanship must be put right by the contractor at his own expense. The contract

administrator will usually mark the end of the defects liability period with the issue

of a further certificate, known as a Certificate of Making Good Defect. Subsequently,

final certificate will be issued to the contractor stating amount finally due to him.

Generally, final certificate will discharge the contractor’s liability for the defective

works and the cost for remedying them. Employers will need to be wary as they can

preclude the employer from claiming damages from the contractors for defects which

appear after the issue of the final certificate. However, court will generally not regard

a certificate as being final except where very clear words are used in the contract.

This research intends to identify the legal position of the construction contract parties

in relation to their rights and liabilities in defects after the issuance of Final

Certificate. This research was carried out mainly through documentary analysis of

law journals and law reports. Result shows that there are four circumstances to be

considered when determining the liability of defects after final certificate, namely by

referring to the conclusiveness evidence, consequential damages/loss, patent defects

and fraud/concealment.

ABSTRAK

Kebanyakan borang kontrak standard mengandungi peruntukan mengenai

kerja-kerja cacat. Kecacatan kerja adalah kesalahan reka bentuk, bahan binaan atau

kemahiran kerja. Segala kecacatan, kekurangan atau kesalahan yang muncul semasa

pembinaan dan tempoh liabiliti kecacatan yang disebabkan oleh kecacatan bahan

atau kemahiran kerja mesti dibetulkan oleh kontraktor dengan perbelanjaannya

sendiri. Pentadbir kontrak akan menandakan akhirnya tempoh liabiliti kecacatan

dengan perakuan siap memperbaiki kecacatan. Kemudian, perakuan muktamad akan

dikeluarkan dengan menyatakan jumlah akhir yang dijangka untuk kontraktor.

Secara umum, perakuan muktamad akan melepaskan liabiliti kontraktor untuk kerjakerja cacat dan kos untuk memperbaikinya. Majikan perlu berhati-hati kerana ini

boleh menghalang majikan daripada menuntut ganti rugi daripada kontraktor jika

kecacatan berlaku selepas perakuan muktamad. Bagaimanapun, mahkamah tidak

akan menganggap satu perakuan sebagai satu keterangan yang tidak boleh

dipertikaikan kecuali perkataan yang jelas digunakan dalam kontrak. Kajian ini

bertujuan untuk mengenalpasti kedudukan sah pihak-pihak kontrak pembinaan

berkaitan dengan hak-hak dan liabiliti dalam kecacatan kerja yang berlaku selepas

pengeluaran perakuan muktamad. Kajian ini telah dijalankan dengan menganalisis

laporan

undang-undang.

Keputusan

menghasilkan

empat

keadaan

yang

dipertimbangkan dengan liabiliti kecacatan kerja selepas perakuan muktamad, iaitu

dengan merujuk kepada bukti jilid, kerosakan/kerugian akibat, kecacatan jenis

‘latent’ dan penipuan/penyembunyian yang jelas.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER

1

2

TITLE

PAGE

DECLARATION

ii

DEDICATION

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

iv

ABSTRACT

v

ABSTRAK

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

vii

LIST OF TABLES

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

xii

LIST OF CASES

xiii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

xvi

INTRODUCTION

1

1.1

Background Studies

1

1.2

Problem Statement

5

1.3

Objective of Research

7

1.4

Scope of Research

8

1.5

Importance of Research

8

1.6

Research Methodology

9

DEFECTIVE WORKS

11

2.1

Introduction

11

2.2

Type of Defects

13

CHAPTER

TITLE

2.3

2.4

PAGE

Nature of Defects

15

2.3.1 Standard of Design

17

2.3.2 Quality of the Building Materials

19

2.3.3 Quality of the Workmanship

20

Liability for Defects

21

2.4.1 Defects discovered during the Construction Period

23

2.4.2 Defects Discovered during Defects Liability

24

Period

2.5

2.6

3

2.4.3 Defects Discovered after the Final Certificate

25

Contractor Obligations after Completion

27

2.5.1 Defects Liability Period

27

2.5.2 Procedural Requirements

31

Conclusion

35

LIABILITY OF DEFECTS

36

3.1

Introduction

36

3.2

Certificate of Making Good Defects

38

3.3

Final Certificate

39

3.3.1 Express Contractual Provisions

41

3.3.2 Conclusiveness of Final Certificate

46

Defects Arising After Issue of Certificate of Making Good

47

3.4

Defects/Final Certificate

3.5

4

3.4.1 Cause of Action in Contract

49

3.4.1 Cause of Action in Tort

50

3.4.1 Postponement of the Limitation Period

52

Conclusion

53

EMPLOYER’S RIGHTS AND CONTRACTOR’S LIABILITIES

55

IN RELATION TO CONSTRUCTION DEFECTS AFTER

FINAL CERTIFICATE

4.1

Introduction

55

CHAPTER

TITLE

4.2

PAGE

Conclusiveness of Final Certificate

56

4.2.1 James Png Construction Pte Ltd v Tsu Chin Kwan

Peter

56

4.2.2 Shen Yuan Pai v Dato Wee Hood Teck & Ors

58

4.2.3 Sa Shee (Sarawak) Sdn Bhd v Sejadu Sdn Bhd

60

4.2.4 Chew Sin Leng Construction Co v Cosy Housing

61

Development Pte Ltd

4.2.5 Usahabina v Anuar Bin Yahya

62

4.2.6 P & M Kaye Ltd v Hosier & Dickinson Ltd

63

4.2.7 Matthew Hall Ortech Ltd v Tarmac Roadstone Ltd

65

4.2.8 University Fixed Assets Limited v Architects

66

Design Partnership

4.2.9 Crown Estate Commissioners v John Mowlem and

68

Co Ltd

4.3

Consequential Loss

69

4.3.1 Teh Khem On & Anor v Yeoh & Wu

69

Development Sdn Bhd & Ors

4.3.2 James Png Construction Pte Ltd v Tsu Chin Kwan

71

Peter

4.3.3 Shen Yuan Pai v Dato Wee Hood Teck & Ors

72

4.3.4 P & M Kaye Ltd v Hosier & Dickinson Ltd

72

4.3.5 HW Nevill (Sunblest) Ltd v William Press & Son

73

Ltd

4.4

Latent Defects

75

4.4.1 P & M Kaye Ltd v Hosier & Dickinson Ltd

75

4.4.2 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham v

76

Terrapin Construction Ltd

4.5

4.4.3 Matthew Hall Ortech Ltd v Tarmac Roadstone Ltd

77

Fraud / Concealment

79

4.5.1 Musselburgh and Fisherrow Co-operative Society

79

v Mowlem Scotland

CHAPTER

TITLE

PAGE

4.5.2 William Hill Organisation Ltd v Bernard Sunley

81

and Sons Ltd

4.6

5

Conclusion

83

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

85

5.1

Introduction

85

5.2

Summary of Research Findings

85

5.3

Problem Encountered During Research

88

5.4

Further Studies

89

5.5

Conclusion

89

REFERENCE

91

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE NO.

5.1

TITLE

Summary of Research Findings

PAGE

86

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE NO.

TITLE

PAGE

1.1

Practical Completion and Defects Liability

5

1.2

Flow chart of research methodology

10

LIST OF CASES

CASES

Abdul Gaffar v Chua Kwang Yong [1994] 2 SLR 546

53

Adcock’s Trustee v Bridge R.D.C.[1911] 75 J.P. 241

19

Archer v Moss [1971] 3 BLR 1

53

Aubum Municipal Council v ARC Engineering Pty Ltd [1973] NSWLR 513

18

Bagot v Stevens, Scanlan and Co [1964] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 353

49

Bolton v Mahadeva [1972] 2 All ER 1322

22

Carr v JA Berriman Pty Ltd [1953] 27 ALJR 273

32

Chew Sin Leng Construction Co v Cosy Housing Development Pte Ltd [1988] 1 MLJ

137

61

Crown Estate Commissioners v John Mowlem and Co Ltd [1994] 70 BLR 1

68

Dancom Engineering Pte Ltd v Takasago Thermal Engineering Co Ltd 1989 BLD

[May] 606

Dutton v Bogner Regis United Building Co Ltd & Anor [1972] 1 QB 373

16

49, 50

Gilbert-Ash (Northern) Ltd v Modern Engineering (Bristol) Ltd [1973] 3 WLR 42137

Greaves & Co (Contractors) Ltd v Baynham Meikle & Partners [1975] 1 WLR 1095

17

H W Nevill (Sunblest) Ltd v William Press and Son Ltd [1981] 20 BLR 78

Hancock v Brazier [1966] 2 All ER 901

26, 73

37

Hancock v BW Brazier (Anerly) Ltd [1966] 2 All ER 901, [1966] 1 WLR 1317 20, 21

Hii Soo Chiong v Board of Management [1973] 2 MLJ 204

15

Hoenig v Issacs [1952] 2 All ER 176

21

IBA v EMI Electronics Ltd & BICC Construction Ltd [1980] 14 BLR 1

18

James Png Construction Pte Ltd v Tsu Chin Kwan Peter [1991] 1 MLJ 449

56, 71

Kabatasan Timber Extraction Co v Chong Fat Shing [1969] 2 MLJ 6

34

Kemayan Construction Sdn Bhd v Prestara Sdn Bhd [1997] 5 MLJ 608

30

Khong Seng v Ng Teong Kiat Biscuit Factory Ltd [1963] MLJ 388

20

Leo Teng Choy v Bectile Construction [1982] 2 MLJ 302

15

London Borough of Barking and Dagenham v Terrapin Construction Ltd [1972] 1

WLR 146

76

Lynch v Thorne [1956] 1 WLR 303

21

Martin v McNamara [1951] QSR 225.8 Butterworths

19

Matthew Hall Ortech Ltd v Tarmac Roadstone Ltd [1997] 87 BLR 96

65, 77

Miller v Krupp [1992] 11 B.C.L.74

23

Musselburgh and Fisherrow Co-operative Society v Mowlem Scotland [2006] CSOH

39

79

Oldschool v Gleeson (Construction) Ltd [1976] 4 BLR 103, 131

18

P & M Kaye Ltd v Hosier & Dickinson Ltd [1972] 1 WLR 146

63, 72, 75

P&M Kaye Ltd v Hosier & Dickinson Ltd [1972] 2 All ER 121

39, 43, 46, 47

P&M Kaye Ltd v Hosier & Dickson Ltd [1972] 1 W.L.R. 146

25, 26, 29

Pearce & High Limited v Baxter [1969] 2 MLJ 6, [1999] BLR 101

32, 34, 35

Pirelli General Cable Works Ltd v Oscar Faber & Partners [1983] 2 AC 1

51

Rumbelows Ltd v Firesnow Sprinkler AMK and Installations Ltd [1980] 19 BLR 25

20

Sa Shee (Sarawak) Sdn Bhd v Sejadu Sdn Bhd [2000] 5 MLJ 414

60

Sequerah Stephen Patrick v Penang Port Commission [1990] 2 MLJ 232

53

Shen Yuan Pai v Dato Wee Hood Teck [1976] 1 MLJ 16

44, 58, 72

Sparham-Sounter v Town & Country Development (Essex Ltd) [1976] 3 BLR 70

50

Steven Phoa Cheng Loon &72 Ors v Highland Properties Sdn Bhd & 9 Ors [2000]

AMR 3567

51

Sutcliffe v Chippendale & Edmondson [1971] 18 BLR 149

22

Teh Khem On & Anor v Yeoh & Wu Development Sdn Bhd & 3 ors [1995] 2 AMR

1558 by analogy

44, 69

University Fixed Assets Limited v Architects Design Partnership [1999] 64 Con LR

12

66

Usahabina v Anuar Bin Yahya [1998] 7 MLJ 691

62

William Hill Organisation Ltd v Bernard Sunley and Sons Ltd [1982] 22 BLR 1

81

William Tomkinson & Sons v Parochial Church Council of St Michael [1990] 6

Const. LJ 319, 814

Young and Marten Ltd v Mc Manus Child Ltd [1969] 1 AC 454

24, 30, 34

19, 20

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AC

Appeal Cases, House of Lords

All ER

All England Law Reports

ALJR

Australia Law Journal Reports

AMR

All Malaysia Reports

BCL

Building and Construction Law Cases

BLR

Building Law Reports

Con LR

Construction Law Reports

CSOH

Court of Session (Outer House)

ER

Equity Reports

ICR

Industrial Cases Reports

ILR

International Law Reports

IR

Irish Reports

JP

Justice of the Peace / Justice of the Peace Reports

LIL Rep

Lloyd’s List Reports

Lloyd’s Rep

Lloyd’s List Reports

MLJ

Malayan Law Journal

NSWLR

New South Wales Law Reports

QB

Law Reports: Queen’s Bench Division

QSR

Queensland State Reports

SC

Session Cases

SCR

Supreme Court Reporter

SLR

Singapore Law Reports

WLR

Weekly Law Report

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1

Background Studies

Construction in Malaysia spans a wide spectrum of activities stretching from

simple renovation works for private homes to massive construction projects. Every

such building activity may create its own unique set of requirements and

circumstance. The different sectors including employer groups, contractors, suppliers,

manufacturers, professionals have their own interests which are very often divergent

and competing in nature.1

Most formal building or engineering contracts contain an initial express

obligation of the contractor in some such words as to “carry out and complete the

works in accordance with the contract”. This is, in fact a dual obligation that is, both

to carry out and to complete the works.2 The contractor’s basic obligation, so far as

the standard of work is concerned, is to comply with the terms of the contract. This

includes both express terms (such as the requirement of contract that work shall be of

1

Sundra Rajoo. “The Malaysian Standard Form of Building Contract (the PAM 1998 Form).” 2nd

Edition. (Malayan Law Journal Sdn Bhd, 1999). pp. 3

2

I. N. Duncan Wallace. “Hudson’s Building and Engineering Contracts.” 11th Edition. (Sweet &

Maxwell, 1995) pp. 472

2

the standards described in the bills) and implied terms (such as the principle that all

materials shall be of ‘satisfactory quality’).3

In a construction contract, a contractor undertaking to do work and supply

materials impliedly undertakes4:

a) to do the work undertaken with care and skill or, as sometimes expressed,

in a workmanlike manner;

b) to use materials of good quality. In the case of materials described

expressly this will mean good of their expressed kind and free from

defects. (In the case of goods not described, or not described in sufficient

detail, there will be reliance on the contractor to that extent, and the

warranty (c) below will apply);

c) that both the workmanship and materials will be reasonably fit for the

purpose for which they are required, unless the circumstances of the

contract are such as to exclude any such obligation (this obligation is

additional to that in (a) and (b), and will only become relevant, for

practical purposes in any dispute, if the contractor has fulfilled his

obligations under (a) and (b)).

The contractor’s obligation only comes to an end when the Certificate of

Practical Completion is issued. Only defects due to workmanship and materials not

in accordance with the contract are required to be made good at the contractor’s cost.

In the context of defective work, the express or implied obligation to carry

out and complete the works in accordance with the contract imposes a continuity

dual obligation, and not merely, as in other contracts for work and materials where

work is not carried out on and fixed to the owner’s land as it progresses, a single

3

Murdoch, J and Hughes, W. “Construction Contracts: Law and Management.” (London: Spon Press,

2000) pp. 147

4

I. N. Duncan Wallace. Supra 2. pp. 519.

3

ultimate obligation to handover and deliver a final conforming product or article on

completion.5 In addition to this principal express or implied obligation to complete,

formal English-style contracts may make express reference to “substantial

completion” or “practical completion”. These definitions are often used in formal

contracts to denote the start of the maintenance or “defects liability” period and to

secure the release to the contractor of the first portion of any “retention moneys”. In

general, what is contemplated by these expressions is a state of apparent completion

free of known defects which will enable the owner to enter into occupation and make

use of the project, with the result that they will usually bring any possible liability of

the contractor for liquidated damages for delay to an end. The scheme of this type of

contract thus contemplates the commencement of a period when the owner enters

into occupation but at the end of which any then known omissions or defects will be

made good by the contractor.6

In most of the standard form of building or engineering contract, there are

provisions dealing with defective works. Defective works could be in the forms of

design fault, defective building materials or bad workmanships. In construction

contracts, the works cannot be said to have been practically completed, if the work is

so defective that it would prevent the owner from using the building as intended by

the contract. For example, sub-clause 15.1 of PAM 1998 form of contract specifies

that the works shall be deemed to be practically completed if the architect is of the

opinion that all necessary works specified by the contract have been completed and

the defects existing in such works are ‘de minimis’.7 Clause 45(a) of JKR 203 form

of contract specifies that the contractor is responsible for any defect, imperfection,

shrinkage, or any other fault which appears during the Defects Liability Period,

which will be six (6) months from the day named in the Certificate of Practical

Completion issued, unless some other period is specified in the Appendix.8 Similarly

in CIDB 2000 form of contract, Clause 27.1 specifies that the contractor shall

5

I. N. Duncan Wallace. Supra 2. pp. 473

I. N. Duncan Wallace. Supra 2. pp. 474

7

Mohd Suhaimi Mohd Danuri. “The Employer’s Rights and the Contractor’s Liabilities in Relation to

the Defects Liability Period.” (The Malaysian Surveyor. 39.1, 2005). pp. 54

8

Lim Chong Fong. “The Malaysian PWD Form of Construction Contract.” (Malaysia: Sweet &

Maxwell Asia, 2004) pp. 105

6

4

complete any outstanding work and remedying defects during the Defects Liability

Period.

Once the works have been practically completed and the Certificate of

Practically Completion issued, the Defects Liability Period will begin. Any defects,

shrinkages or other faults arising during this period due to defective materials or

workmanship must be put right by the contractor at his own expense.9 For example,

sub-clause 9(a) of PWD 203A requires the contractor to use materials and

workmanships that comply with the specification, further, sub-clause 9(b) entitles the

superintendent to instruct the contractor to demolish or open up the work done and

the associated cost will be borne by the contractor if the works have not carried out

in accordance with the contract.

The contract administrator will usually mark the end of the defects liability

period with the issue of a further certificate, known as a Certificate of Making Good

Defect. This record the contract administrator’s opinion that defects appearing within

the Defects Liability Period and notified to the Contractor have been duly made good.

The contractor is then entitled to the remainder of the retention money. This last

portion of the retention is the amount finally due to the contractor. It is the contract

administrator’s obligation to issue the Final Certificate that signifies his satisfaction

with the work.

9

Murdoch, J and Hughes, W. Supra 3. pp. 184

5

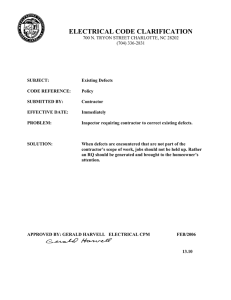

Contractor carries out and completes the

works as stipulated in the contract

Contractor’s work is to the reasonable

satisfaction of the contract administrator

CERTIFICATE OF

PRACTICAL COMPLETION

Contract administrator specifies all defects

and requires defects to be made good

CERTIFICATE OF

MAKING GOOD DEFECTS

FINAL

CERTIFICATE

Figure 1.1

1.2

Practical Completion and Defects Liability10

Problem Statement

In Malaysia, section 74(3) of Contracts Act 1950 (Revised 1974) provides

that the innocent party is entitled to get compensation for the failure of the defaulting

party to discharge the obligation created by the contract. Therefore, the failure of the

contractor to rectify the defects appear during Defect Liability Period (DLP) as

required by the contract would constitute a breach of contract that entitles the

employer to be remedied in the forms of damages. If the contractor has failed to

rectify the defects as instructed by the contract administrator, the owner is entitled to

10

Sundra Rajoo. Supra 1. pp. 147

6

appoint another contractor and recover the cost of rectifying the defects to the

original contractor.11

However, Employers will need to be wary of Final Certificates as they can

preclude the Employer from claiming damages from the Contractor for defects which

appear after the issue of the Final Certificate. Generally, a Final Certificate will be

binding and conclusive and cannot be opened up except in the cause of fraud.

However, court will generally not regard a certificate as being final except where

very clear words are used. Therefore, the conclusiveness of the Final Certificate

depends upon the terms of the particular contract.12

Both PAM 1998 (Clause 30.8) and JKR 203 (Clause 49) form of contract

states that “No certificate….shall be considered as conclusive evidence as to the

sufficiency of any work, materials or goods to which it relates ….” This clause

primarily states that none of the certificates issued under the contract would be

treated as conclusive evidence as to the sufficiency of any work done, or material or

goods supplied, which is the subject matter of the certificate. The contents of the

certificates will not be final and binding in any dispute between the parties either in

arbitration or in court. In other words, all certificates can be opened up, reviewed and

revised by the arbitrator or the court.13

However, the provision in the CIDB 2000 form of contract is different with

PAM 1998 and JKR 203. Clause 43.2 of CIDB 2000 states that the Final Certificate,

unless either party commences any mediation, arbitration or other proceedings within

30 days after such certificate, shall be conclusive evidence that the works are

executed to the reasonable satisfaction of the Superintending Officer and/or

Employer.

11

Mohd Suhaimi Mohd Danuri. Supra 7. pp. 57

Mallesons Stephen Jaques, 2003. “Defects Liability Period - an introduction. Asian Projects and

Construction Update.”

http://www.mallesons.com/publications/Asian_Projects_and_Construction_Update/6881582W.htm

13

Lim Chong Fong. Supra 8. pp. 114

12

7

There is existence of problems arise in relation to the conclusiveness of the

Final Certificate. The first is whether the Employer is prevented from recovering

damages for any defects which appear after the issuance of the Final Certificate? The

second is whether the contractor is liable for defects which come to light after the

issuance of Final Certificate? And ultimately, whether the contractor or the employer

is liable for defects which come to light after the issuance of Final Certificate?

In view of the above, it is important for the contracting parties in the

construction industry, especially the clients and the contractors, to have a complete

understanding to their rights and liability in relation to the defects which appear after

the issuance of Final Certificate.

1.3

Objective of Research

From the problem statement above, this research is prepared with an

objective:

To identify the legal position of the construction contract parties in

relation to employer’s rights and contractor’s liabilities in defects after the

issuance of Final Certificate.

8

1.4

Scope of Research

Given the legalistic nature of this research, the approach adopted in this

research is based on case-law. The scope of this research will cover the following

areas:

a) Only construction cases will be discussed in the research.

b) Court cases referred in this research include Malaysia, Singapore, and

English cases.

c) Standard forms of contract commonly referred to and examined in this

research are Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia (PAM) (2nd Edition, 1998),

Public Works Department (P.W.D) Form 203A and Construction Industry

Development Board (CIDB) Standard Form of Contract for Building

Works (2000 Edition).

1.5

Importance of Research

This research will deal closely with specific issues or problems arise between

the contract parties with regards to construction defect after expiry of Defect

Liability Period (DLP). The author aims to assist both clients and contractors in the

construction industry to understand their rights and liability in relation to defects

which come to light after the issue of the Final Certificate. This research is also to

increase the awareness of the construction parties about their legal position in the

liability of defect, so that unnecessary disputes can be avoided and assuring project

success and tie-up a better relationship among the contractual parties.

9

1.6

Research Methodology

In order to achieve the research objectives, a systematic process of

conducting this research had been organised. The detail methodology is divided into

several essential steps as described below (see figure 1.2 also).

Firstly, initial literature review was done in order to obtain the overview of

the concept of this topic. Discussions with supervisor, lecturers, as well as course

mates, were held so that more ideas and knowledge relating to the topic could be

collected. The issues and problem statement of this research will be collected through

books, journal, cases, articles and magazines. The objective of this research will be

formed after the issue and problems had been identified.

The next stage is the data collection stage. After the research issue and

objectives have been identified, various documentation and literature review

regarding to the research field will be collected to achieve the research objectives.

Generally, primary data is collected from Malayan Law Journals and other law

journals via UTM library electronic database, namely Lexis-Nexis Legal Database.

The secondary sources include books, articles, seminar papers, newspaper as well as

information from electronic media database on the construction contract law. These

sources are important to complete the literature review chapter.

After the data collection stage, the author will analyse all the collected cases,

information, data, ideas, opinions and comments. This is started with the case studies

on the related legal court cases. The analysis will be conducted by reviewing and

clarifying all the facts and issues of the case.

The final stage of the research process mainly involved the writing up and

presenting the research findings. The author will review the whole process of the

10

research with the intention to identify whether the research objectives have been

achieved. Conclusion and recommendations will be made based on the findings

during the stage of analysis.

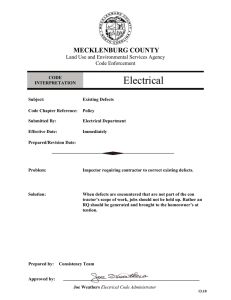

Literature Review

Books, articles, journals, internet sources

INITIAL STAGE

Brief Discussion

Discussion with lecturers, supervisor and

coursemates

Formation of issues, objective and scope of

research

DATA

COLLECTION &

ANALYSIS STAGE

Identify type of data needed and data sources

Law Journals, e.g. Malayan Law Journal,

Singapore law Report, Building Law

Report, etc

Books, articles, seminar papers, newspaper

Internet sources

Data Recording

Data Arrangement

Analyse data

Research writing up and presenting findings

FINAL STAGE

Conclusion and recommendation

Final report preparation and checking

Figure 1.2

Flow chart of research methodology

11

CHAPTER 2

DEFECTIVE WORKS

2.1

Introduction

Defective work can be described as work which fails to comply with the

express descriptions or requirements of the contract, including very importantly any

drawings or specifications, together with any implied terms as to its quality,

workmanship, performance or design. By definition, therefore, defects are breaches

of contract by the contractor14.

Most standard forms of construction contract will contain express terms

concerning the removal and replacement of defective work during construction. The

usual scheme of such contracts is to confer express powers on the owner or his

architect, engineer or the contract administrator for this purpose during the

construction period up to the time of completion and handover.15 In addition to this,

14

15

Mallesons Stephen Jaques. Supra 11.

I. N. Duncan Wallace. Supra 2. pp. 698.

12

these standard forms usually contain detailed provisions in respect of the employer’s

remedies in respect of defective works, e.g.16:

a)

Defective work to be remedied by contractor

b)

Defective work to be remedied by employer if contractor fails to do so

c)

Employer may agree to a reduction of contract price instead of

remedying the defect

d)

Employer may deduct the cost of remedial works from the contract

price until the remedial works are carried out

e)

Employer to withhold retention monies, to be released upon issuance

of the Certificate of Practical Completion and/or Certificate of

Making Good Defects.

In most situations, there is also a contract provision which requires the

contractor to take full responsibility and liability for the rectification works if the

defects are due to a breach of contract. Defective works are works which fails to

comply with both the expressed descriptions or requirements and implied terms of

the contract affecting the quality of the works, whether structural on one hand or

merely decorative on the other, and whether due to faulty materials or workmanship

or even design (if such design is part of contractor’s obligations under the contract).17

The general principle is that such defective works which amounts to a breach

of contract would entitle the employer to claim for damages notwithstanding other

contractual remedies which the employer may have under the contract or at common

law. The common law, on the other hand, requires that the contractor carry out and

complete the works in accordance with the contract. This obligation, whether express

or implied, places an obligation on the contractor to hand over a final conforming

product or article on completion. Failure to remedy the defect is a breach of contract,

16

Ong See Lian. 2005. “Defective Works.” International Conference on Construction Law &

Arbitration. (26th – 28th April 2005, Kuala Lumpur.) pp. 1.

17

Ong See Lian. Ibid. pp. 1.

13

even if the defect occurred during the period of construction, i.e. prior to completion

or handing over of the final works. The employer is entitles to damages.18

Once the works have been practically completed and the Certificate of

Practical Completion issued, the Defect Liability Period (DLP) will begin. The

Contractor will be liable to rectify the defects, which appear during DLP at the

contractor’s own cost. For example, Clause 15 of PAM 1998 and Clause 45 of JKR

203 provide two ways of notifying the contractor for rectifying the defects during

DLP as follows19:

a)

At any time during DLP, the Architect/Superintending Officer can

request the contractor in writing to make good the defects within

reasonable time; and

b)

Architect/Superintending Officer not later than 14 days after the

expiry of DLP issues schedule of defects to be made good by the

contractor within reasonable time; but in JKR 203 it clearly specifies

that the defects to be made good by the contractor not later than 3

months after receiving the schedule.

2.2

Type of Defects

Defects can be classified into two main categories, i.e. ‘Patent’ defects and

‘Latent’ defects. The first category encompasses the usual defects encountered in

routine inspections. Professor Vincent Powell-Smith describes a ‘patent’ defect as20:

18

Ong See Lian. Supra 15. pp. 1.

Mohd Suhaimi Mohd Danuri. Supra 7. pp. 54

20

Harbans Singh. “Engineering and Construction Contracts Management – Post Commencement

Practice.” (Singapore: LexisNexis, 2003.) pp. 695

19

14

“A defect which is discoverable by reasonable inspection. In the context of

engineering contracts, the term embraces all the items which the engineer or

engineer’s representative must be expected to find and bring to the contractor’s

attention so the remedial works can be carried out. Patent defects are plain to

see, or at least, that is the theory. Whether the engineer could or should have

seen defects on site during site visits has exercised more than one judicial

mind…”

In ‘Construction Law in Singapore and Malaysia’, the authors ascribe a rather

simple definition to the term ‘patent defects’; this being21:

“… a defect that can be discovered by normal examination or testing…”

As to the second category of defects, i.e. ‘Latent’ defects, the same two

references ascribe the following definitions/meanings22:

“A defect which is not discoverable during the course of ordinary and

reasonable examination but which manifests itself after a period of time. In

building and civil engineering work the most common application is defects

becoming apparent after the maintenance period expired.”

Robinson and Lavers describe a ‘latent’ defect in the following words23:

“… a defect that cannot be discovered by normal examination and testing…”

In essence patent defects are defects that can be either seen or can be

discovered by means of reasonable inspection, examination or testing. Hence, the

21

Nigel M Robinson. “Construction Law in Singapore and Malaysia.” 2nd Edition. (Butterworths Asia

Malaysia, 1996) pp. 160

22

Harbans Singh. Supra 19. pp. 696

23

Nigel M Robinson. Supra 20. pp. 161

15

establishment of such defects is not merely confined to the defects that can be plainly

seen or observed but encompasses also those that become apparent on reasonable

inspection, examination and if necessary upon testing. The latter requirement to

testing imposes a more onerous responsibility in terms of discoverability. In contrast,

latent defects are the ones that are either inherent or those that do not manifest

themselves upon reasonable examination, inspection and/or testing. These comprise

defects which will become apparent or noticeable or capable of being discovered

only when they become patent.24

In the definitions for both categories of defects, the emphasis is on the words

‘normal’ or ‘reasonable’ whether these can be in relation to any inspection or

examination or testing in establishing the type of defect in question. The requirement

therefore does not call for a meticulous or exhaustive process in establishing the said

defects. The difference between these two types of defects also extends to their

consequential effects especially in terms of duration of liability, with latent defects

involving a longer duration both contractual and under various statutory provisions.25

2.3

Nature of Defects

A ‘defect’ must be defined as a component supplied or constructed which is

in some respect not in accordance with the contract, or as some action having

consequences not authorised by the contract. Thus, the criteria of acceptability of

performance must, in contract, be limited to those criteria expresses or implied in the

contract: see Hii Soo Chiong v Board of Management26, Leo Teng Choy v Bectile

Construction 27 and Dancom Engineering Pte Ltd v Takasago Thermal Engineering

24

Harbans Singh. Supra 19. pp. 696

Harbans Singh. Ibid. pp. 696

26

[1973] 2 MLJ 204

27

[1982] 2 MLJ 302

25

16

Co Ltd

28

. The implied terms require ‘merchantable quality’, ‘workmanlike’

workmanship and fitness for purpose.29 Express terms are commonly either30:

a) Compliance with the contract’s specification content and the drawings;

b) Satisfaction of the architect (or other supervisor); or

c) Both these

The construction work is defective when it does not accord with the standard

that is required by the contract. For example, Clause 9(a) of JRK 203 and Clause 6.1

of PAM 1998 requires the contractor to use materials and workmanships that comply

with the specifications. The obligation of the contractor to procure and achieve the

specified kind and standard is an absolute one. If the contractor fails to do so, he

would be in breach of contract unless the Superintending Officer is willing to permit

a substitution by way of a variation instruction.31 Further, Clause 9(b) of JKR 203

and Clause 6.3 of PAM 1998 empowers the superintendent to require the contractor

to demolish or open up the work done for inspection and associated cost will be

borne by the contractor if the works have not been carried out in accordance with the

contract. 32 The purpose for opening up and testing is to ensure that the works,

materials, workmanship and goods are ‘in accordance to the contract’. If the

contractor is not in default, he can recover the cost of opening up, testing and making

good. He may also have a right under the contract to claim for extension of time and

recover any direct loss and/or expense cause by the opening up and testing which

disturb the regular progress of the works. This ensures the superintendent act with

moderation.33

Generally, defects in the construction industry can be well divided into three

(3) main categories34:

28

1989 BLD [May] 606

Nigel M Robinson. Supra 20. pp. 160

30

Nigel M Robinson. Ibid. pp. 160

31

Lim Chong Fong. Supra 8. pp. 29

32

Mohd Suhaimi Mohd Danuri. Supra 7. pp. 55

33

Sundra Rajoo. Supra 1. pp. 97

34

Mohd Suhaimi Mohd Danuri. Supra 7. pp. 55

29

17

2.3.1

a)

Faulty design and work not in compliance with design

b)

Quality of the building materials

c)

Quality of the workmanship

Standard of Design

The term ‘design’ has been explained by Prof Vincent Powell-Smith as35:

“A rather vague denoting a scheme or plan of action. In the construction and

engineering industry, it may be applied to the works of the engineer in

formulating the function, structure and appearance of a works or to a structural

engineer in determining the sizes of structural members…”

By that as it may, the undertaking of the design may not be confined to the

employer’s designers but may be the obligation of the contractor whereby quality

standards may be either36:

a) Stipulated expressly in the contract, i.e. in the specifications, standards,

codes of practice, etc and reaffirmed through specific clauses in the

conditions of contract

b) In the absence of express provisions, established by necessary implication,

ie a contractor undertaking a contract on a design and build/design and

construct basis implicitly warrants that where the purpose of the required

works has been adequately brought to his notice, the design undertaken

by him will be fit for that purpose37.

35

Harbans Singh. Supra 19. pp. 698

Harbans Singh. Ibid. pp. 698

37

Greaves & Co (Contractors) Ltd v Baynham Meikle & Partners [1975] 1 WLR 1095

36

18

Therefore, design is wide enough to include (and include correctly) not

merely structural calculations and the dimensions, shape and location of the work,

but the choice of particular materials for particular functions and, similarly, the

choice of particular work processes. In other words, in sophisticated contracts the

designs includes the specification as well as the drawings.38

If the contractor is required to use a design and construct method, the

contractor shall be responsible for the proposed design directly to the owner flowing

from the breach. This is likely to arise where an architect or engineer is not engaged

by the employer. Generally, design and build method imposes on the contractor a

duty to ensure the building would be reasonably fit for its purpose39. However, in the

traditional contracting method, the design responsibility shall remain under the

responsibility of the consulting engineer or the architect. In Oldschool v Gleeson

(Construction) Ltd40, Judge Stabb QC said:

“The responsibility of the consulting engineer is for the design of the engineering

components of the works and his supervisory responsibility is to his client to

ensure the works are carried out in accordance with that design.”

If the defects were proven to be faulty of engineer’s design, the owner can

sue the engineer for breach of contract41. On the other hand, if the defect is flowing

from the contractor’s fault such as departure from the actual design, the contractor

should be liable to remedy the defect.42

38

I. N. Duncan Wallace. Supra 2. pp. 274.

IBA v EMI Electronics Ltd & BICC Construction Ltd [1980] 14 BLR 1

40

[1976] 4 BLR 103, 131

41

Aubum Municipal Council v ARC Engineering Pty Ltd [1973] NSWLR 513

42

Mohd Suhaimi Mohd Danuri. Supra 7. pp. 55

39

19

2.3.2

Quality of the Building Materials

Building and engineering contracts usually define with some precision in the

specification or bills the materials to be used by the contractor. The contractor shall

be held responsible if the building materials appear to be defective although its usage

has been specified by the contract specification. Materials may be said to be of poor

quality when what is meant is that they have been chosen for the wrong purpose, as

common bricks for facing bricks, or iron cramps for zinc.43 The House of Lords in

Young and Marten Ltd v Mc Manus Child Ltd44 held that, the Court of Appeal was

correct when it decided that the contractor was liable for an implied warranty of the

defective material bought from the manufacturer specified by the owner.

In another case of Martin v McNamara45, the Full Court reversed the decision

of the Magistrate Court and held that, the owner was relying on the skill and

judgement of the contractor that the materials were fit for the intended purpose when

the contractor had suggested to use a different type of roof tiles that turned out to be

faulty. The owner should be entitled to the cost of removing and replacing the faulty

materials if the repair work was unreasonably to be carried out. However, it would be

unreasonable to put the liability on the contractor, if the owner has accepted the

material to be used although the contractor has made known to the owner that the

specified manufacturer excluded any warranty of quality.

Undoubtedly, however, as a general rule the contractor’s obligation will not

extend beyond supplying a material of good quality conforming to the express

description of it in the contract documents, if the description is precise and the choice

of the material is indeed the architect’s and engineer’s. 46 The quality standards

expected of the contractor are either47:

43

I. N. Duncan Wallace. Supra 2. pp. 274.

[1969] 1 AC 454

45

[1951] QSR 225.8 Butterworths

46

Adcock’s Trustee v Bridge R.D.C.[1911] 75 J.P. 241

47

Harbans Singh. Supra 19. pp. 697

44

20

a) Expressed in the contract, i.e. in the form of specifications, employer’s

requirements, etc; these being reaffirmed vide appropriately drafted

conditions of contract, e.g. Clause 1.1 of Pam 1998 Form, Clause 15.1 of

CIDB 2000 Form; and/or

b) Established by necessary implication, e.g. materials supplied must be of

‘merchantable quality’ and fit for their purpose 48 , these two criteria

operating independently and exclusively49.

2.3.3

Quality of the Workmanship

The standard of workmanship may be defined in considerable detail by the

contract, for example by requiring it to comply with an appropriate code of

practice. 50 Under PAM 1998, such a requirement would appear in the contract

document, and would have contractual force by virtue of Clause 6.1. Clause 6.1 of

the PAM 1998 provides that the specification of the works contain in the contract

document will specify the kinds and standard of materials, goods and workmanship.

Where the standards are described in the contract documents, the materials, goods

and workmanship must be of those standards. Where the standards are not expressly

described in the contract documents, then the implied duties of the contractor

apply.51 In a situation where the contract document do not so specify, there will be an

implied term that the materials or goods will be of merchantable quality and that the

workmanship will be carried out with reasonable care and skill: see Lord Denning in

Hancock v BW Brazier (Anerly) Ltd52 and Lord Reid in Young and Marten Ltd v Mc

Manus Childs Ltd53.

The owner can still accept minor defective workmanship as a substantial

performance of the contractor’s work. Indeed, the owner can bring an action to

48

Khong Seng v Ng Teong Kiat Biscuit Factory Ltd [1963] MLJ 388

Rumbelows Ltd v Firesnow Sprinkler AMK and Installations Ltd [1980] 19 BLR 25

50

Murdoch, J and Hughes, W. Supra 3. pp. 148

51

Sundra Rajoo. Supra 1. pp. 95

52

[1966] 2 All ER 901

53

[1969] 1 AC 454

49

21

counterclaim the cost of the repair works and set-off from the money due under the

building contract. In Hoenig v Issacs54, the Court of Appeal agreed with the official

referee’s finding that the contract has been substantially performed even though there

were some defects and held that the contractor was entitled to be paid the balance

due, less only a deduction for the cost of making good the defects.

The standards of workmanship to which the contractor must aspire to work

towards are either55:

a) Prescribed in the contract in an express manner. These are usually

contained in the form of the specifications, standards, code of practice, etc,

and endorsed by the relevant express clauses, e.g. clause 4 of JKR 203

Form, and/or

b) Implied under the general corpus of the law, e.g. workmanship has to be

of ‘workmanlike’ standard, i.e. that which an employer could reasonably

expect of an ordinarily skilled and experienced contractor of the type the

employer has elected to employ and having regard to any relevant claims

made by the contractor as to his level of competence56. It is to be noted

that where a contractor has complied exactly with a detail express

specification, there is no room for implication of further provision as to

the standard required to be achieved 57.

2.4

Liability for Defects

As a general principal, defects in the work do not entitle the employer to

terminate the contract and refuse payment altogether. The employer’s remedy is to

54

[1952] 2 All ER 176

Harbans Singh. Supra 19. pp. 698

56

Hancock v BW Brazier (Annerley) Ltd [1966] 1 WLR 1317

57

Lynch v Thorne [1956] 1 WLR 303

55

22

claim damages for the cost of rectification. However, very serious defects may

justify the conclusion that there has nor been ‘substantial performance’ by the

contractor. Where this can be established, the employer need pay nothing.58 In Bolton

v Mahadeva 59, the installation of a central heating system at an inclusive price of

£560 was defectively carried out. The system was only 90% efficient (70% in some

rooms) and gave off fumes in the living room. The Court of Appeal held that the

claimant was entitled to nothing for this work; the defendant was not limited to

setting of the £174, which it would cost to put right the defects.

It is even possible that an accumulation of lesser defects may amount to a

repudiatory breach of contract, even though none of them would be sufficient on

their own.60 It was thus held in the case Sutcliffe v Chippendale & Edmondson61 that

the contractors’ ‘manifest inability to comply with the completion date requirements,

the nature and number of complaints from sub-contractors and their own admission

that…the quality of work was deteriorating and the number of defects was

multiplying’ entitled the employer to terminate the contract and to order the

contractors to leave the site. The employer had justifiably concluded that the

contractors had neither the ability, competence nor the will to complete the work

accordance with the contract.

Timing wise, the contractor’s liability for defects can be demarcated along

three principal stages of a typical contract, namely during construction, during

defects liability period and post defects liability period.

58

Murdoch, J and Hughes, W. Supra 3. pp. 328

[1972] 2 All ER 1322

60

Murdoch, J and Hughes, W. Supra 3. pp. 329

61

[1971] 18 BLR 149

59

23

2.4.1

Defects discovered during the Construction Period

This stage encompasses the period from the commencement of the contract

up to the issue of the certificate of practical completion or sectional completion.

During this stage, the general rule is that the contractor is entitled or has a contractual

right to remedy any patent defect or latent defect becoming patent, at anytime up to

the date of handing over of the works to the employer. Should he fail to remedy to

rectify such defects either on his own or upon instruction of the contract

administrator, he is culpable of breach of contract.62

The architect, engineer or the contract administrator in most standard forms

has extensive powers in respect of63

(i)

opening up and investigation of works; and

(ii)

remedial of defects, e.g. to have defects remedied including removal

and substitution of defective materials and removal and re-execution

of defective work.

Notwithstanding the engineer or the contract administrator supervisory role,

the contractor is solely responsible for compliance with the contract. Failure of the

engineer or the contract administrator to give notice or investigate defects is not

sufficient ground to construe the engineer or the contract administrator has accepted

the works64. In Miller v Krupp65, NSW, Giles J. said:

“Krupp’s [defendant contractor] submission requires that Miller’s [plaintiff

employer] agent for the purpose of supervising Krupp’s performance of the

contract owed a duty to take care to prevent Krupp from falling properly to

perform: a duty to save it from breach of the very contract it had to perform to

62

Harbans Singh. Supra 19. pp. 709

Ong See Lian. Supra 15. pp. 2.

64

Ong See Lian. Ibid. pp. 2.

65

[1992] 11 B.C.L.74

63

24

Miller’s satisfaction. In my view there was not the requisite proximity, a view

confirmed by notions of what is fair and reasonable.”

It should be noted that the commensurate redress is usually stipulated under

the contract itself, i.e. for mere trivial breaches amounting to breach of warranty, the

employer’s right being confined normally to the use of third parties or a financial

adjustment and for a more serius default constituting a breach of a condition, the

remedy being determination of employment. 66 In William Tomkinson & Sons v

Parochial Church Council of St Michael67, it was held that the employer was entitle

to recover damages for the defective work as it was still a breach of contract, despite

occurring during the construction period. Damages which the employer would be

entitle to recover however is not his outlay in remedying the damage but the cost

which the contractor would have incurred in remedying it if they had not been

required to do so; the sum is anticipated to be much less than the actual remedial

costs.

2.4.2

Defects Discovered during Defects Liability Period

The instant stage normally covers the period from the date of completion or

handing over up to the certification by the contract administrator of the contractor’s

obligation to remedy defects, i.e. by the issue of the Certificate of Making Good

Defects.68 During the defects liability period, which starts on the completion of the

works, standard forms of contract generally give the contractor a licence to return to

the site for the purpose of remedying defects. In effect, such condition of contract

confers upon the contractor a right to repair or make good its defective works, which

can (usually) be carried out more cheaply and (possibly) more efficiently than by

some outside contractor bought in by the employer69.

66

Harbans Singh. Supra 19. pp. 711

[1990] 6 Const. LJ 319

68

Harbans Singh. Supra 19. pp. 711

69

Ong See Lian. Supra 15. pp. 3.

67

25

Lord Diplock, commenting on RIBA/JCT defects liability clause in the case

of P&M Kaye Ltd v Hosier & Dickson Ltd70, said:

“Condition 15 imposes upon the contractor a liability to mitigate the damage

caused by his breach by making good the defects of construction at his own

expense. It confers upon him the corresponding right to do so. It necessary

implication from this that the employer cannot, as he otherwise could, recover

from the contractor the difference between the value of the works if they had been

constructed in conformity with the contract and their value in their defective

condition, without first giving the contractor the opportunity of making good the

defects.”

It follows that an employer who chose to repair the defects himself without

giving the contractor an opportunity to do so would thereby be in breach of contract71.

2.4.3

Defects Discovered after the Final Certificate

The post “correction” period starts at the end of the defects liability period.

The contractor will no longer have a right of entry or a right to remedy his own

defects, although many standard forms provide a short transition period for the

contractor to enter and remedy defects notified up to the end of the defects liability

period72.

In the absence of words to the contrary in the contract, the contractor’s

liability for not completing the works in accordance with the contract continues until

statute barred. The Malaysia Limitation Act 1953 Section 6(1) provides that the

70

[1972] 1 W.L.R. 146, at p.166

Ong See Lian. Supra 15. pp. 3.

72

Ong See Lian. Ibid. pp. 3.

71

26

limitation period for a breach of contract and tort are six year from the date on which

the cause of action accrued. A cause of action for ordinary failure to build in

accordance with the contract normally arises at practical completion. A cause of

action for failure to comply with defects liability obligations normally arises at the

end of the defects liability period or such period prescribed by the contract for

carrying out these defects obligations.73

Note, however, the exception under section 29 of the Act, where the action is

based upon the fraud of the defendant or his agent or of any person through whom he

claims or his agent, or the right of action is concealed by the fraud of any such

person, then the period of limitation shall not begin to run until the plaintiff has

discovered the fraud or the mistake (as the case may be) or could with reasonable

diligence have discovered it.74

It appears following H W Nevill (Sunblest) Ltd v William Press and Son Ltd 75

that the satisfactory making good of defects does not amount to an exclusion of

claims in respect of their consequences. The measure of damages will therefore not

only be the cost of repair of the defect, but also such compensation as the loss of the

use of the plant during repairs in accordance with the ordinary rules governing

remoteness of damage.

Where there is a conclusive final certificate of satisfaction given by the

architect, engineer or the contract administrator, the contractor’s liability for the

defective works ends upon the end of Defects Liability Period, notwithstanding that

the certificate may have been granted after the commencement of legal proceedings

in respect of the defects in question76.

73

Ong See Lian. Supra 15. pp. 3.

Ong See Lian. Ibid. pp. 4.

75

[1981] 20 BLR 78

76

Kaye (P&M) Ltd v Hosier & Dickinson [1972] 1 W.L.R. 147 (HL)

74

27

2.5

Contractor Obligations after Completion

There are further obligations imposed on the contractor after completion,

notably by JKR 203, PAM 1998 and CIDB 2000. Clause 45 of JKR 203 governs the

rights and obligations of the parties on defects, imperfections, shrinkages and other

faults in the works which arises during the Defects Liability Period (DLP) after

achievement of practical completion of the works. Clause 45(a) specifies that the

contractor is responsible for any defect, imperfection, shrinkage and other fault

appears during the DLP, which will be six months from the day named in the

Certificate of Practical Completion (CPC), unless some other period is specified in

the Appendix. 77 Clause 15.2 under PAM 1998 also specifies the liabilities of the

contractor after the CPC has been issued. It establishes a formal DLP and a

procedure for dealing with defects within that period. 78 CIDB 2000 also has the

similar provision under Clause 27.1.

2.5.1

Defects Liability Period

The exact status of the ‘Defects Liability Period’ (or ‘Maintenance Period’),

is of a period defined in the construction contract during which the appearance of

defects is at the contractor’s own risk in that he may be called upon to return to site

to correct them as nessasary. This was traditionally a period of six months but is now

commonly specified as 12 months. 79 Under the Housing Developers (Control and

Licensing) Act 1966, the standard pro-forma agreement which must be used for the

sale of units within building projects contains the following basic provision: (the

wording is from Clause 23 of Schedule G in the Housing Developers Regulations)

77

Lim Chong Fong. Supra 8. pp. 105.

Sundra Rajoo. Supra 1. pp. 145.

79

Nigel M Robinson. Supra 20. pp. 170

78

28

“Any defects, shrinkage or other faults in the said Building which shall become

apparent within a period of eighteen (18) calendar months after the date of

handing over of vacant possession, to which water and electricity supply are

ready for connection to the said building, to the purchaser and which are due to

defective workmanshio or materials or the said Building not having been

constructed in accordance with the plans and description as specified in the

Second and Fourth Schedule as approved or amended by the Appropriate

Authority, shall be repaired and made good by the Vendor at its own cost and

expenses within thirty (30) days of its having received written notice thereof from

the Purchaser and if the said defects, shrinkage or other faults in the said

Building have not been made good by the Vendor, the Purchaser shall be entitled

to recover from the Vendor the cost of repairing abd making good the same and

the Purchaser may deduct such costs from any sum which has been held by the

Vendor’s solicitor as stakeholder for the Vendor: Provided that the Purchaser

shall, at any time after the expiry of the said period of theirty (30) dais, notify the

Vendor of the cost of repairing and making good the said defects, shrinkage or

other faults before the commencement of the works shall give the Vendor an

opportunity to carry out the works himself within fourteen (14) days from the

date of the Purchaser has notified the Vendor of his intention to carry out the

said works.”

Note that this contractual term deriving from the Housing Developers

Regulations is operative only as between the purchaser of the housing unit and the

vendor (developer); where the developer has contracted with a contractor for the

construction of the building, the terms of that contract may be quite different.80 The

requirement in the Housing Developers Regulations is limited to “any defect,

shrinkage or other fault … which shall become apparent …”. The sufficiency or that

requirement depends on the definition of completion adopted within the contract and

on the strict enforcement of it. It is not necessary the case that items pf work required

by the contract but remaining outstanding at the date of acceptance ov completion are

80

Nigel M Robinson. Supra 20. pp. 170-171

29

to be classified as defects or faults, but the Defects Liability Period nay be used also

for the completion of such items.81

It is to be noted that under most of the construction contracts, the issue of the

“Certificate of Practical Completion” marks the start of the “Defects Liability

Period”. Any defects, shrinkages or other faults arising during this period due to

defective materials or workmanship must be put right by the contractor at its own

expense. The contractual procedure for dealing with defects arising during the

Defects Liability Period is that the contract administrator should issue a schedule of

such defects to the contractor not later than fourteen days after the end of the defects

liability period, and the contractor then has a reasonable time to put them right. Once

this has been done, the contract administrator will issue a ‘Certificate of Completion

of Making Good Defects’, following which the contractor becomes entitled to the

remaining part of the retention money. It may be noted that, if no schedule of defects

is issued, the employer retains the right to claim damages for breach of contract.82

It is the contractor’s obligation under the contract to rectify the defects

appears during DLP. According to Lord Diplock in P&M Kaye Ltd v Hosier &

Dickinson Ltd83, the DLP’s clause is included in the contract with an intention of

giving opportunity to the contractor to make good the defects appear during that

period. Lord Diplock’s interpretation is easy to understand as we could see that most

of the construction contracts require the superintendent to issue notice to the

contractor for rectifying the defects appear during DLP. Further Lord Diplock said

that:

“…the contractor is under an obligation to remedy the defects in accordance

with the architect’s instructions. If he does not do so, the employer can recover

as damages the cost of remedying the defects, even though this cost is greater

than the diminution in value of the works as a result of the unremedied defects.”

81

Nigel M Robinson. Supra 20. pp. 171

Murdoch, J and Hughes, W. Supra 3. pp. 185.

83

[1972] 1 WLR 146

82

30

During a defects liability period, the contractor has the right as well as the

obligation to put right any defects that appear. What this means is that an employer

who discovers defects should operate the contractual defects liability procedure,

rather than appoint another contractor to carry out the repairs. In William

Tompkinson v Parochial Church Council of St Michael84 , an employer refused to

allow the original contractor access to the site to remedy defects, but instead sued the

contractor for the cost of having these rectified by another contractor. It was held that

the employer’s decision amounted to an unreasonable failure to mitigate the loss

suffered, and the damages were reduced by the amount by which the employer’s

costs exceeded what it would have cost the original contractor to carry out the work.

The Court of Appeal has since approved this decision.

Therefore, in the event that the contractor is fails to rectify the defects after

being given notice or the owner is not satisfied with the remedial works, the owner is

entitled to appoint another contractor to undertake the remedial work and claim the

cost of doing it to the original contractor.85 This has been correctly decided by the

High Court of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur in Kemayan Construction Sdn Bhd v Prestara

Sdn Bhd 86 where the owner is entitled to recover the cost of rectification of the

defective building works from the original contractor who failed to rectify the defects

after being instructed by the Architect. It was held that the owner is entitles to engage

independent contractor to rectify the defects and deducted the rectification cost from

the original contractor’s account. Kamalanathan JC agreed that the owner may

recover from the contractor or may deduct any money due or to become due to the

contractor provided that the architect has issued a written notice to the contractor to

rectify the defects and that at the expiry of seven days notice, it has been shown that

the contractor has failed to rectify the defects.

84

[1990] 6 Const LJ 814

Mohd Suhaimi Mohd Danuri. Supra 7. pp. 56

86

[1997] 5 MLJ 608

85

31

It is also worth noting that defects liability clauses do not act as exclusion

clauses. If a defect is not included on a schedule of defects, and is not noticed by the

contractor or contract administrator before the end of the period, the contractor is still

liable for it. Since the period has expired, the contractor has no right to return to the

site to repair the defect, but is liable to the employer for damages.87

2.5.2

Procedural Requirements

In all cases, the strict entirety of the contract is modified and provision is

made for the making good of defects by the contractor subsequent to handing over

possession. The employer’s right to have defects remedied within a stipulated period

after completion is in substitution for his rights to a damages claim in respect of the

cost of remedial work dine by another contractor, i.e. the provision for the making

good of defects by the contractor is mandatory on both parties and gives the

contractor the right to make good defects notified to him rather than be sued by

breach.88

Where the contract stipulates the procedural requirements, the parties must

observe the requirements to preserve their respective rights. Failure of the employer

to comply with procedural requirements in respect of defects rectification may be

detrimental to his later claim for damages.89

Accordingly, it is generally accepted that the owner would be entitled to

appoint another contractor to rectify the defects if the original contractor had failed to

comply with the said notice. However, the issue would be much difficult if the owner

employ another contractor to rectify the defects without first giving the required

notice to the original contractor. In another words, it deprives the original contractor

87

Murdoch, J and Hughes, W. Supra 3. pp. 185.

Nigel M Robinson. Supra 20. pp. 171

89

Ong See Lian. Supra 15. pp. 4.

88

32

from having the opportunity to undertake the remedial works himself. It must be

noted that the owner cannot employ another contractor to do work that the original

contractor is obliged to do under the contract. 90 The common law principle has

justified that the works under the contract cannot be omitted with an intention of

giving it to another contractor.91

In considering this issue, it is essential to appreciate that the requirement of

such notices impliedly imposing a duty to mitigate the loss on the owner. Refer to the

decision of the Court of Appeal in Pearce & High Limited v Baxter92 , P&H, the

building contractor sued Baxter, the employer for amounts including the sum of BGP

3,919.23 outstanding under an architect’s certificate for workdone under a contract in

the JCT form for Minor Building Works. Defects had become apparent before the

end of the defects liability period, but these were not notified to the contractor. The

Court of Appeal held that the owner was under a duty to mitigate the loss by giving

the opportunity to the original contractor to undertake the remedial works himself.

The judge justified that the cost of employing another contractor to remedy the

defects would be much higher than the cost to the original contractor. Evans LJ said

that:

“The cost of employing a third party repairer is likely to be higher that the cost

to the contractor doing the work himself would have been. So the right to return

in order to repair the defects is valuable to him. The question arises whether, if

he is denied that right, the employer is entitled to employ another party and to

recover the full cost of doing so as damages for the contractor’s original breach.

In my judgement, the contractor is not liable for the full cost of repairs in those

circumstances. The employer cannot recover more than the amount which it

would have cost the contractor himself to remedy the defects. Thus, the

employer’s failure to comply with clause 2.5 (the clause relating to rectification

of defects), whether by refusing to allow the contractor to carry out the repair or

90

Mohd Suhaimi Mohd Danuri. Supra 7. pp. 56

Carr v JA Berriman Pty Ltd [1953] 27 ALJR 273

92

[1999] BLR 101

91

33

by failing to give notice of defects, limits the amount of damages which he is

entitled to recover. The result is achieved as a matter of legal analysis by

permitting the contractor to set off against the employer’s damages the amount

which he, the contractor, has been disadvantaged by not being able or permitted

to carry out the repairs himself, or more simply, by reference to the employer’s

duty to mitigate his loss.”

The employer’s failure to comply Clause 2.5 of the JCT form for minor

works, whether by refusing to allow the contractor to carry out the repairs or by

failing to give notice of the defects, limits the amount of damages whish he is

entitled to recover. As a matter of legal analysis this is either93:

a) By permitting the contractor to set-off against the employer’s damages

claim the amount by which he, the contractor, has been disadvantaged by

not being able or permitted to carry out the repairs himself, or

b) By reference to the requirement for the employer to mitigate the loss for

which is entitled to recover damages

The measurement of damages was therefore the cost of repairs by the

contractor if he remedied the defects himself on the assumption that this is lower

than the cost of repair by a third party. The absence of notice of the defect does not

raise the possibility that the measure of damages in some circumstances may only be

the diminution of the value of the property by reason of the defect, on normal

principles. The decision was not concerned with this aspect however and left the

question open.94

In Malaysia, the principle of mitigating the damages is stipulated in the

explanation to section 74 of the Contracts Act 1950 (revised 1974). It has been

93

94

Ong See Lian. Supra 15. pp. 5

Ong See Lian. Ibib. pp. 5

34

decided in the case of Kabatasan Timber Extraction Co v Chong Fat Shing95 that the

respondent is under a duty to mitigate the damages, when the appellant had failed to

deliver some of the timbers to the designated site. Macintyre FJ in that case has said

that:

“In the instant case, there was no need for the respondent to have gone to the

expense and trouble of buying logs from elsewhere when the logs were lying a few

hundred feet away from the sawmill for the mere taking and all that was required

was additional expense for hauling them up to the sawmill.”

Furthermore, Macintrye FL also quoted the following passage from Anson’s

Principles of the English Law of Contract:

“it also follows from the rule that damages are compensatory only that one who

has suffered loss from a breach of contract must take any reasonable steps that

are available to him to mitigate the extent of the damage caused by the breach.

He cannot claim to be compensated by the party in default for loss which is really

due not to the breach but to his own failure to behave reasonably after the

breach.”96

Therefore, the probability is that the courts in Malaysia will follow the same

principles developed in the case of Pearce & High Limited v Baxter97 by imposing

the owner a duty to mitigate the damages for defects appear during Defects Liability

Period. It has to be noted that the failing of the superintendent to issue the required

notice during DLP shall not bar the owner from appointing another contractor to

rectify the defects and recovering the remedial cost. In this regards, Evans LJ has

agreed with the judgement of Judge Stannard in William Tokinson v St Michaels’s

Parochial Church Council

95

98

that the owner’s common law right to recover for

[1969] 2 MLJ 6

Kabatasan Timber Extraction Co v Chong Fat Shing [1969] 2 MLJ 6

97

[1969] 2 MLJ 6

98

[1990] CLJ 319

96

35

damages is not excluded by failing to issue such a notice, however, it would limit the

damages recoverable by the owner due to the principle of mitigating the damages.99

2.6

Conclusion

It is important to understand the precise nature of the defects obligations

under the contract. It involves basically the right to recall the contractor to return to

the site to carry out rectification works even if the site was returned to the employer