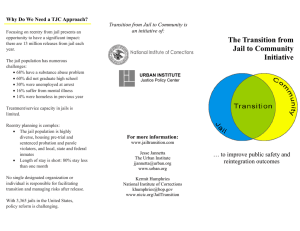

Partnering with Jails to Improve Reentry A Guidebook for

advertisement