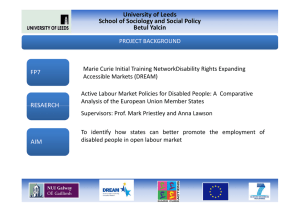

EMPLOYERS’ VIEWS ON EMPLOYMENT OF DISABLED PEOPLE: Betul YALCIN

advertisement