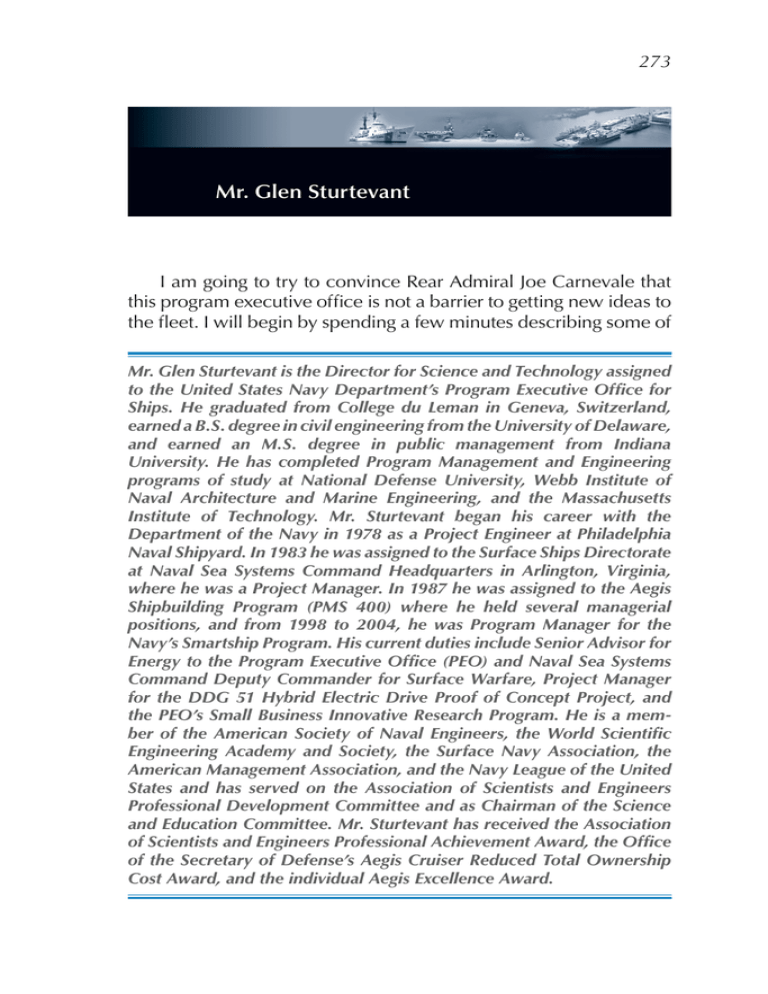

Mr. Glen Sturtevant

advertisement

273 Mr. Glen Sturtevant I am going to try to convince Rear Admiral Joe Carnevale that this program executive office is not a barrier to getting new ideas to the fleet. I will begin by spending a few minutes describing some of Mr. Glen Sturtevant is the Director for Science and Technology assigned to the United States Navy Department’s Program Executive Office for Ships. He graduated from College du Leman in Geneva, Switzerland, earned a B.S. degree in civil engineering from the University of Delaware, and earned an M.S. degree in public management from Indiana University. He has completed Program Management and Engineering programs of study at National Defense University, Webb Institute of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Mr. Sturtevant began his career with the Department of the Navy in 1978 as a Project Engineer at Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. In 1983 he was assigned to the Surface Ships Directorate at Naval Sea Systems Command Headquarters in Arlington, Virginia, where he was a Project Manager. In 1987 he was assigned to the Aegis Shipbuilding Program (PMS 400) where he held several managerial positions, and from 1998 to 2004, he was Program Manager for the Navy’s Smartship Program. His current duties include Senior Advisor for Energy to the Program Executive Office (PEO) and Naval Sea Systems Command Deputy Commander for Surface Warfare, Project Manager for the DDG 51 Hybrid Electric Drive Proof of Concept Project, and the PEO’s Small Business Innovative Research Program. He is a member of the American Society of Naval Engineers, the World Scientific Engineering Academy and Society, the Surface Navy Association, the American Management Association, and the Navy League of the United States and has served on the Association of Scientists and Engineers Professional Development Committee and as Chairman of the Science and Education Committee. Mr. Sturtevant has received the Association of Scientists and Engineers Professional Achievement Award, the Office of the Secretary of Defense’s Aegis Cruiser Reduced Total Ownership Cost Award, and the individual Aegis Excellence Award. 274 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 the operational testing we are doing to reduce the risk associated with the follow-on acquisition of some important technologies. In my view, there are three key things to think about. I believe that the energy imperative is now driving innovation, but I submit to you that the real innovation is in the application of that technology. Secondly, I think we all need to adapt faster. We should not be forcing the adaptation on the back of the operators in the fleet; the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations staff resources requirements, the Office of Naval Research, scientific research, technology development, the shipbuilders, the program executive offices, and the systems commands need to adapt faster if we are going to get ahead of the power curve with respect to energy. And lastly, if you think you understand all of the consequences of your decisions today, then I submit you are wrong. We adapted this idea from commercial shipping. We start easy. Basically, we are going to go out and survey our ships. It is all about collecting the data, making improvements, and then validating those improvements. It is basic stuff. We design ships—the best ships in the world. But I will tell you, we really do not know where the energy goes today. We know how we design our ships and where the electricity and fuel goes for those designs, but many of our existing ships are 10, 15, 20, or 25 years old, and we really do not know where the energy goes. So we are going to find out. We are going to measure it. We originally called it an audit, but the crews did not like the word “audit,” so we are calling it an energy survey. We are starting simple to make sure we are chasing the sweet spot and not some red herrings and to make sure we are not investing in the wrong areas for improvement. I am going to talk about four technologies. As you will see, we have adapted a lot of things from commercial shipping, from the airline industry, and from government and industry labs. I am going to talk about a handful of these and what we are doing today, how we trying to get operational feedback, and how we plan to reduce risks for the follow-on acquisition programs. So here is the list. As you can see (Figure 1), we have categorized these technologies according to their expected availability—be it 2012, 2016, or Chapter 8 Adapting Ship Operations to Energy Challenges 275 farther in the future. By 2012 we will have the Green Strike Group, and by 2016, we will have the Great Green Fleet. I have highlighted four of these technologies; in what follows, I will describe how we are taking these to sea and how we think we are going to make a difference. Figure 1. Energy Efficiency Enabling Technologies Let us start with hybrid electric drive, which you have already heard something about. In Figure 2, we show the drive system for a DDG-51-class destroyer. We have three gas turbine generators over to the left. They generate electricity and make up half the system. The propulsion plant is on the right. We actually have four LM-2500 gas turbine engines on USS Truxton, the proof-of-concept ship. Next January, we will be taking a subscale system out to the ship. As shown in the center of Figure 2, it includes the basic electric motor on the main reduction gear, along with a converter and switchboard. Ultimately, we will be powering the electric motor through the gas turbine generators that have been moved to a more efficient location aboard ship, the way they were originally designed. When you do not need all the power that the gas turbines provide, you can turn them off and run the ship through the water at low rates of speed using electricity. 276 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 Figure 2. DDG-52 Hybrid Electric Drive That is the idea. Initially, it is all about fuel efficiency. But once you field the hybrid electric drive, you are likely to find that the operators will say “well, geez that kind of changes everything.” Now they will have a new quiet speed that can be used by DDG51s conducting antisubmarine warfare operations. Or, it could prove beneficial for destroyers conducting ballistic missile defense missions in the Mediterranean. Maybe it changes the transit speed when the ship crosses the Atlantic. Perhaps 16 knots is not the best speed for that evolution. So, once we make that innovative design change, we are likely to find that it is followed by innovative application changes. We stole the idea for the Smart Voyage Planning Decision Aid (Figure 3) from the commercial airline industry. When you fly from here to Los Angeles, it is all about altitude and heading. It turns out that Maersk, the largest American commercial shipping line, has adapted the idea to ship routing. They have come up with a pretty sophisticated tool that directs the ship where to go in order to save gas. By adapting that approach for the Navy, we are projecting that perhaps as much as 8% fuel savings could result from using the most fuel-economic route. Airplanes take advantage of the jet stream, why can’t we take advantage of the Gulf Stream? Chapter 8 Adapting Ship Operations to Energy Challenges 277 Figure 3. Smart Voyage Planning Decision Aid For years we have done optimum track ship routing to avoid bad weather that bangs up the ship and injures the crew. If we can lay the toolset for the ship router, or something that has local weather conditions, into the Voyage Planning Decision Aid, then perhaps we can route our ships based on weather and get better gas mileage, recognizing of course that mission comes first. So, we are going to start doing that. We intend to roll out this system in time to support Pacific Fleet’s participation in Exercise Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2012 next year. Figure 4 illustrates our test plan for surface ship alternate fuels. Starting with the upper-left-hand corner, you see the rigid hull inflatable boat (RHIB). We tested a 50/50 blend in a RHIB down in Little Creek back in July 2010. In October, we tested a Riverine Control Boat experimental craft (RCB-X). We are going to test alternate fuel on a yard patrol (YP) craft at the Naval Academy this spring and on an LCAC down in Panama City this summer. Next year, we are going to test use of alternate fuel on an FFG coming out of commission or on the Navy’s self-defense test ship (SDTS) in Port Hueneme, California. In June 2012, we will test alternate fuels with the Green Strike Group (GSG) during RIMPAC 2012. Our basic approach is to “build a little, test a little.” We are also doing component testing ashore. 278 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 Figure 4. Alternate Fuel Test Plan The important point is that using the alternate fuel will have no impact whatsoever on the operator. We are designing drop-in fuels. The operators will not know the difference. That is the model we are following now for a lot of our technologies. We are not putting the burden on the back of the warfighters. They already have enough to worry about. My final example is what Rear Admiral Philip Cullom called “the box on the bridge.” We have labeled it the “energy dashboard.” Commercial shipping uses this extensively. It is a way to try to influence the actions of the operators. If you know exactly where your fuel is going, where your electricity is going, then perhaps you can take actions to use that fuel or energy more efficiently. The large arrow in Figure 5 is my way of showing that you may want to send that data off the ship, which is what commercial shipping does. They have found that by pitting one ship against another, they can significantly change the energy consumption behavior of their ship masters. Chapter 8 Adapting Ship Operations to Energy Challenges 279 Figure 5. Energy Dashboard One of the real powers of this energy tool is that you can overlay the material condition of the ship onto the display. You will know that the sea grass on the hull is increasing your drag. You will know that you have a bad generator that you did not know about before. You can also lay the maintenance of the material piece into the energy dashboard. We are going to field this in one of our destroyers—the USS Chafee—later this year. We will get it out to other ships as we move forward.