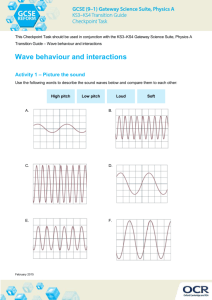

T h e

advertisement