Business Ethics Dr Richard Kwiatkowski

advertisement

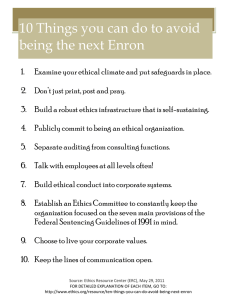

Business Ethics Dr Richard Kwiatkowski SM The issue of ethics in organisations seems to have come to the fore in this recession. In the UK we have had MP’s expenses in Parliament; we have had the spectre of Enron and the behaviour that was exhibited there and how that reflects in other organisations. To discuss this today we have Richard Kwiatkowski. Now Richard, tell me something about ethics in organisations; I know you have spent a lot of time looking at this. RK It’s a very complicated issue and not wishing to be a moral relativist about it, because there are clearly right and wrong actions. It is actually very difficult sometimes for people when they are embedded within organisations to spot what those right and wrong actions are. SM Well this all very well – you are saying it’s difficult. Each manager is faced with this dilemma, am I doing the right thing or not? RK And it is important to think about where is your reference. If you are within an organisation, particularly if you are embedded within an organisation and most of your contact is with other people in that organisation, you very rapidly become socialised into the morays, the norms, the ways of thinking, the ways of behaving of that organisation. That whole notion that Schein talks about, the way we do things around here, the culture is very powerful. SM I mentioned Enron earlier on, I guess that is a classic example of that? RK It is really, and I think the issue there is that people behaved in a certain sort of way because it was seen as the norm. It was seen as normal, it was seen as acceptable; in fact it was seen as very exciting and rather sexy to be doing these amazing things financially – but as we discovered, the emperor really had no clothes. SM I talked a bit about this recession, in banking lots of people have said we just sat there and let all these bad practices go on. Why didn’t people speak out? RK Well there can be all sorts of different reasons. First of all it is very difficult to break from the herd; it takes a lot of courage, a lot of integrity and a lot of personal strength in terms of things like virtue, ethics. We would think about how are people developing those things? So the consequences of blowing the whistle or for saying we have to stop the train right now can personally be very, very difficult. Secondly, if everybody is doing it, it seems normal; it seems acceptable. And it’s very hard to step out from that and that is what people have to do – step out from that and say how does this look? Is this actually right? Is this appropriate? © Cranfield University July 2009 1 Dr Richard Kwiatkowski SM So if you were to say to people well what sort of moral and ethical compass should you hold in your organisation – how would you respond to that? RK In terms of ways of thinking about ethics, the two main approaches if you like are the deontological and the utilitarian. And the deontological approach says essentially do unto others how you would have done unto you. And in a more complex way, how would it be if everybody in the society acted in a way that you are acting? And if you thought about that and said well, that is absolutely fine, I would be perfectly happy to be on the receiving end of this, and I think that society would function perfectly well if everyone did this, then in a sense that guides your behaviour. So for instance, a society where everybody lied to everybody else would fairly soon break down; you wouldn’t be able to trust people to fulfil contracts or obligations and so forth. The other main approach is the utilitarian approach, which is really talking about the greatest good for the greatest number; increasing the amount of happiness in the world. And so there the question you would be asking is, “Is this action that I am performing, on balance, in terms of its consequences, going to cause more pleasure than pain? Is there going to be more goodness in the world as a result?” SM This is all very well, but most people don’t consider these things. They maybe just have a kind of sense of unease over some things and then just put that aside. An example recently would be the UK MP’s expenses where everybody said well everybody else was doing it, so why not me? RK I think that one of the things that is very important is the thing that you said, Steve, about if you feel unease; and there is almost that sense that if there is something that you feel uneasy about, if there is something that you think oh, should I talk about this or shouldn’t I talk about this? Is this something that I need to conceal? Is this a boundary that is being broken? Is this a step too far? Often there can be a sense of unease and it’s at that point that the discussion needs to take place; that you need to talk about it. Maybe to talk about it with people who can give you some sort of objective view; mentors, colleagues, friends – people who can actually say OK, well this far, yes. This far, it’s starting to look a bit grey, you are right to be uneasy. So there can often be a personal reaction to these things and at that point if you feel as though well maybe this should be concealed, it’s the opposite. At that point you should be being more open, more transparent and discussing those things. And if you feel you can’t do that, then in a sense you probably already have your answer as to whether you have gone too far. SM So your argument would be get these things out in the open. Think about them, talk about them? RK Yes, but it’s very easy to say that because these things can have consequences, particularly for people who blow the whistle, particularly for © Cranfield University July 2009 2 Dr Richard Kwiatkowski people who break rank, people who put their head above the parapet. A lot of these metaphors we use indicate the danger that is associated with these things. So there are also institutional practices and policy level issues that come into play here, which is why the involvement of senior managers and board and the whole notion of transparency and sustainability become so important. SM Now I know here at Cranfield we have set up an ethics committee. Can you say a bit about that? RK One of the important things for universities is that we view ourselves as extremely ethical places. We generate knowledge for the benefit of society; quite a utilitarian view, if you will. However, within that we have to be very careful that we do the right thing, in the right way. Our aims and motives are good, but within that we need to be sure that the research that we are doing is appropriate, that it is fair, doesn’t breach confidentiality, it’s methodologically rigorous, it’s applicable and so forth. And because at the School of Management we work a lot with people, although we do work with secondary data and large databases and so forth, it is important that things like peoples’ individual human rights are respected, confidentiality is respected, data protection is respected and so forth. So that we act in an ethical way, such that our research is sound and ethical and something that we can be proud of. SM Would you recommend that business organisations set up something similar? RK A lot of organisations now have codes of ethics; however simply having a code of ethics is very different from acting ethically and the whole notion of ethics being embedded within organisations rather than just a bolt on is very important. And that is the difference. And again, it’s the culture of the organisation and how that is set from the top of the organisation and what is really done. So rather than just having lip service and saying we have got a code of ethics, we have ticked that box, we are fine; it’s how is that translated into action? And how behaviourally do we , particularly senior people in the organisations, emphasise and re‐emphasise by their actions the importance of ethical behaviour. SM Richard, some timely reminders there, thank you very much. RK Thank you. © Cranfield University July 2009 3