particularly to those writers who wish their poetry to

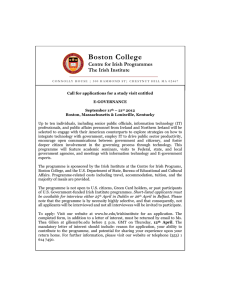

advertisement

particularly to those writers who wish their poetry to connect with traditional music. Dr. Crosson has chosen to focus on a number of poets who have made explicit reference to traditional music in their writings, either in Irish or in English. Having outlined the interaction between music and poetry in early modern Ireland, the study goes on to consider briefly writers from the eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, including Charlotte Brooke, Thomas Moore, Douglas Hyde, W. B. Yeats, Austin Clarke and Patrick Kavanagh. The central development of the book, however, explores in detail the works of six major poets of the last half-century: Thomas Kinsella, Seamus Heaney, Ciaran Carson, writing in English, and Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Cathal Ó Searcaigh and Gearóid Mac Lochlainn writing in Irish. The author’s careful readings and explications of their work begins to explore distinctions between them, the poetry of some being closer to the ethos of traditional music than others. In many cases, traditional music allows the expression of that anxiety that Kinsella first identified as the consequence of the loss of Irish as the language of the majority of the people, whereby “I must exchange one language for another, my native English for eighteenth century Irish”. Crosson argues that allusions to traditional music reflect unease on the part of the poets at the historical discontinuity in Irish writing and the poets’ own uncertain relationship with a contemporary audience. This difficulty does not seem to exist for traditional music, whether instrumental or sung, and so the rituals of performance imply authenticity and a sense of community. While commentators and historians of music, and Crosson himself, would question this simplified view of the music, it nonetheless has been of interest to the poets, and this is the central exploration of this book. By means of detailed readings of the poems, combined with consideration of the metrics of many of them, this book examines in a sensitive and readable study the responses of the six recent poets who are here discussed. It is certainly the most thorough exploration of this subject to date, and combines awareness of music with the practice of poetry in an original and compelling way. Dr. Riana O’Dwyer, Senior Lecturer, English Department, NUI Galway. Order through your supplier; by writing to us at CSP, PO Box 302, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 1WR, UK; by telephone at (US) +1 919 783 4013 or online at www.c-s-p.org. Most major credit cards accepted. Cambridge Scholars Publishing Academic Publishers “The Given Note” Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry by Seán Crosson ISBN: 9781847185693, 34.99 GBP, US$ 69.99, 314pp. This book draws on a wide range of theoretical perspectives to construct an exploratory inquiry detailing and interrogating previously unarticulated connections between words and music. Despite the breathtaking wealth of referential material, the model that emerges is subtle, nuanced and flexible, handled with the sure and elegant touch of one who is supremely aware of the possibilities of effects at the nexus of these two intertwined media…This pioneering work is sure to herald other studies in this rich field of inquiry, and provides an exemplary model which leads the way with confident assurance. Dr. Lillis Ó Laoire, Foreword, “The Given Note” Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry. This book makes an original contribution to the field of Irish Studies. It is particularly impressive in discussing together the normally disparate studies of Irish literature (in both languages), metrics, music and orality studies. The study is clearly well-written in a clean uncluttered style and proceeds with a logic of argument which carries the reader along. Professor Alan Titley, Head of Department of Modern Irish, University College Cork. Seán Crosson, himself a composer and performer, has written a penetrating and nuanced study of the influence of traditional music and song on modern Irish poetry. While it may seem that poetry is inherently musical, since it involves the arrangement of words for their sound values as well as their meanings, this is more difficult to verify than one might imagine. Thus the author has marshalled an impressive range of expertise to explore his initial hunch that the relationship is fundamental, ranging from practitioners of Words and Music Studies through Orality Studies, through Ethnomusicology, and through Literary Theory. Having considered the implications of all of these methodologies, he argues convincingly that a model of “covert intermediality” offers the best explanation for the relationship with contemporary Irish poetry. His initial clarification of the concept of “traditional music” is also exemplary, as he emphasises that transmission of the tradition is oral, where each performance involves a connection with an “authentic” past as well as the creation of a community in the present, something that the poets also try to achieve. For this community to be created, the audience as well as the musicians must submit to the conventions or ritual of the performance: thus the participants are connected to the past in the very act of creating music in the present. This aspect is one that appeals