Austria and United States J. Nina Lieberman

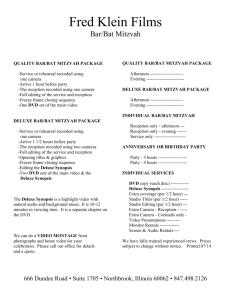

advertisement

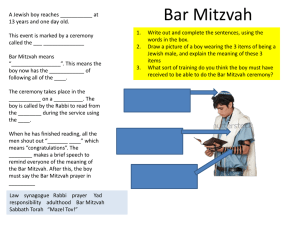

Austria and United States J. Nina Lieberman In everyone’s life, there are many paths that lead to important decisions. So it was when I decided to become a bat mitzvah. I came from a rabbinical home in Austria with a progressive slant. My father encouraged learning in his daughter and always held up to me the example of Beruriah, the wife of Rabbi Meir, a sage living in the Roman era. She was as erudite as her husband, and he listened to her voice. But when it came time to signify our maturity in the mid-1930s, we girls of Salzburg were called up en masse to the bimah on Shavuot and asked to recite the Ten Commandments. Soon world events uprooted me from Austria, and after spending the war years in England, I arrived in the United States in 1946. While earning a livelihood and completing my education, which had been interrupted, I had little time to devote to Hebrew. I was fluent in reading and knowing the meaning of prayers, but without the grammatical underpinnings of the language. I made some efforts, but only by fits and starts. By the time of my retirement from work as a college professor of psychology, my involvement in women’s rights transferred itself naturally to the Jewish religious scene. A bat mitzvah was no longer an oddity. Under the tutelage of a Conservative rabbi, I started to prepare for my bat mitzvah ceremony. My parsha (Torah portion) was Kedoshim (Holy Things, in Hebrew). While the Hebrew gave me no trouble, the cantillation did, since I have no ear for music. I developed a somewhat idiosyncratic way of chanting, which the rabbi accepted as perhaps the way I heard it in Austria. I now call it my “Alpine yodel.” I became a bat mitzvah at age fifty plus thirteen. I have since recited the haftorah (reading from the Prophets) on many occasions, including the yahrzeits (anniversaries of the deaths) of my parents. One Shabbat, we had no rabbi at our synagogue, and a learned talmid chacham (Judaic scholar) felt that the next best person to chant the haftorah was the daughter of a rabbi. I even managed to chant it to the special niggun (cantillation) of Echa (Book of Lamentations), used at that time of year, as that Shabbat was the one before Tisha-be-Av (a fast day commemorating the destructions of the ancient temples in Jerusalem). This was the last prayer I heard my father, Rabbi Dr. David Samuel Margules, recite before he passed away. After my bat mitzvah I was privileged to meet Judith Kaplan Eisenstein, zichronah l’vracha (may her memory be a blessing), the first-ever bat mitzvah in this country, and to count her as a close friend. She introduced me to the term “PK,” meaning preacher’s kid, since my father and hers were rabbis. We started a chug (club) with two other women, reading and speaking Hebrew. When Judith was 83, she repeated the bat mitzvah ceremony. She is no longer with us, and we do not meet as a chug anymore. However, I carry on the study of Hebrew on my own, and will occasionally recite a haftorah. During the recent Simchat Torah morning service I was given the honor of being called up as Kallat Torah (literally, “bride or bridegroom of the Torah,” the person who reads the end of the Torah.) It was the honor that was always given to my father while he held pulpits in Czechoslovakia and Austria. I am now 81, and God willing, may I live, like Judith, to have a second bat-mitzvah at age 83.