Maryland Site Visit Report ACA Implementation—Monitoring and Tracking March 2012

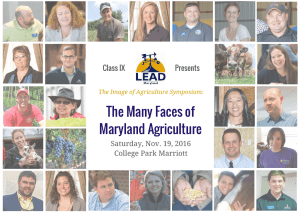

advertisement