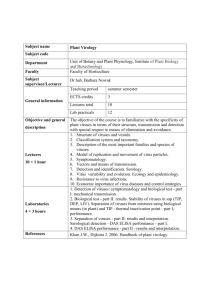

CD–206 •

advertisement

4838 Wilkinson Apps pp 203-241 8/9/99 10:04 AM Page 206 CD–206 • APPENDIX 7.2 A Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) is often contacted to conduct a scientific fraud investigation. The CFE’s first step is to gather and analyze the relevant data to determine whether predication is sufficient to proceed further. Sufficient predication is the basis for creating a hypothesis of a specific fraud. That is, the CFE, based on an evaluation of the initial fraud indicators, decides whether enough evidence exists to proceed further. The next step is to test the hypothesis by gathering sufficient evidence through interviews, document examinations, and observation. At the conclusion of evidence gathering, the CFE prepares a written report that does or does not support the allegation of fraud or is inconclusive. If warranted, the case is turned over to an attorney, who works closely with the CFE to prosecute the case. Fraud and Computer Crime Prevention Safeguards With the massive number of cases of insider theft, fraud, embezzlement, and other crimes reported in the media, management should take proper action to prevent, detect, and deter these risk exposures. Firms should establish and enforce strong soft controls, including a written code of professional conduct, ethics, and personnel policies. Ethical principles should receive increased attention throughout the organization. Sound personnel policies and controls, such as reference checks on employment applications, should be enforced. The corporate audit committee should be independent of management and should closely monitor stakeholders’ interests. A properly developed internal audit function, adequately staffed, can significantly reduce the probability of fraud and other computer crimes. Internal auditors should complete training courses on fraud and computer crime, such as those offered by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners of Austin, Texas. In addition, internal auditors and other accountants involved in the audit function should be encouraged to become Certified Fraud Examiners. A CFE is trained in criminology, legal elements of fraud, interrogation and investigative matters, and financial fraud. Respondents to KPMG’s 1998 Fraud Survey have documented policies and procedures they follow for dealing with fraud. The reported safeguards and controls and the percentage of responding firms reporting them are as follows.* • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • A corporate code of conduct (75%) Reference checks on new employees (65%) Employment contracts (48%) Review and improvement of internal controls (47%) Fraud audit (42%) Ethics training (41%) Training courses in fraud prevention and detection (31%) Surveillance equipment (30%) Increased focus of senior management on the problem (29%) Enhanced surveillance equipment (27%) Code of sanctions against suppliers/contractors (26%) Increased role of audit committee (16%) Surveillance of electronic correspondence (15%) Increased budget for internal audit (13%) Staff rotation policy (11%) Increased budget for security department (9%) Although such crimes can never be eliminated, organizations that adopt the above safeguards can dramatically reduce their vulnerability. *http://www.us.KPMG.com, p. 1. APPENDIX 7.2 COMPUTER VIRUSES AND RELATED RISKS A potentially significant risk exposure to information stored on microcomputers and local-area networks (LANs) is a computer virus. More than 17,000 computer virus strains have been documented, and new ones appear daily. Most viruses have static or unchanging structures that render them relatively easy to detect and destroy with the use of anti-virus software. Anti-virus software checks for, finds, and removes most types of viruses. A computer virus is a computer program that copies or attaches itself to a program file and causes either the display of prankish messages or the destruction of data, such as erasing all the files on a hard disk. Most com- puter viruses attach themselves to either executable or document program files. Currently, macro viruses, which attach to document files of word processing software packages, such as Microsoft Word, are the fastest growing viruses with thousands of documented strains. These viruses are easy to write and easy to spread; they usually enter a PC via e-mail attachments received from the Internet. They, along with other types of viruses, can also be introduced into a microcomputer or a LAN when an infected floppy disk is copied onto a hard disk. Once attached to an executable or document file, a computer virus can remain 4838 Wilkinson Apps pp 203-241 8/9/99 10:04 AM Page 207 APPENDIX 9.1 • • • • • Purchase and use anti-virus software Test all software before copying onto the hard disk Write-protect floppy disks, hard disks Prepare backups on read-only disks of all programs and data files Only use well-respected national bulletin board services that screen all programs for viruses FIGURE A7.2-1 • • • • • • CD–207 Do not download software from unknown public bulletin boards Be leery of demo programs received in the mail from unknown sources Shut down computers when not in use Do not copy pirated software Exercise common sense Security and control measures to safeguard against computer viruses. dormant and undetected for long periods. Usually, the virus will carry out its intended function when it is activated by the computer’s internal clock. If the microcomputer is part of a LAN, the virus can rapidly spread to all microcomputers in the network. For example, the Melissa macro virus infected computer networks worldwide in early 1999. When a computer user opened an infected Microsoft Word e-mail attachment, the virus quickly spread to other computers by reading the user’s e-mail address book and sending the infected attachment to the first 50 addresses. However, no real damage was done by the Melissa virus, compared to other viruses, such as the Chernobyl virus. This dangerous virus destroyed both the data on a computer’s hard disk and also the computer’s BIOS chip, making the computer unbootable. More recent viruses with dynamic structures, called polymorphic viruses, are much more difficult to detect and destroy. Every time a polymorphic virus copies itself onto another program file, it randomly scrambles its program code, creating a new virus strain that is often invisible to the version of the anti-virus software loaded on the desktop or LAN. However, once the new strain has been identified and documented, the anti-virus software will be updated by its developer and made available on its Web page for downloading. A second category of maliciously written program code has virus-like characteristics, but they are not true viruses. This program code is usually written to perform one or more destructive operations; they go by names such as Trojan Horses, logic bombs, and worms. These nonvirus programs are usually illegally patched into a particular software package. The malicious code may be written by dishonest programmers who want to get even with their employers or to commit a computer crime. A Trojan Horse is an unauthorized program code hidden inside an application program that performs a valid function, such as the payroll program. For example, the unauthorized code may activate each pay period to produce a check for the programmer’s mother-in-law. This hidden code enables the programmer to conceal an ongoing computer fraud. Like a virus, a logic bomb is a small program inserted into another program to cause some type of destructive operation. For instance, a programmer threatened with dismissal from his job might plant a logic bomb into accounting application software to destroy the data files maintained on a hard disk. The programmer could set the logic bomb to automatically go off (“explode”) shortly after his or her termination date. A logic bomb is designed to perform only one function. A worm is similar to a logic bomb, except that when activated, it replicates itself by generating random digits that fill up the entire hard disk, thereby crashing the computer system. Security and control measures to safeguard against computer viruses and related virus-like programs include anti-virus software. A suggested list of safeguards is presented in Figure A7.2-1. APPENDIX 9.1 EXAMPLES OF DELIVERABLES TO INCLUDE IN EMERGENCY, BACKUP, AND RECOVERY DISASTER CONTINGENCY PLANS Emergency Plan Important deliverables to include in this plan are the following: 1. An organization chart, showing the chain of command involved in Disaster Contingency and Re- covery Planning (DCRP). Senior management should appoint a DCRP manager and a second in command to lead the DCRP. 2. A risk analysis to rank relevant risks. 3. Emergency responsibilities to be assigned to specific personnel; for example, who is to contact fire, police, and other agencies?