Let Us Continue: Housing Policy in the Great Society, Part One

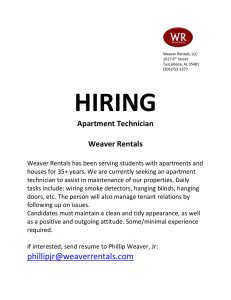

advertisement