Joint Center for Housing Studies Harvard University

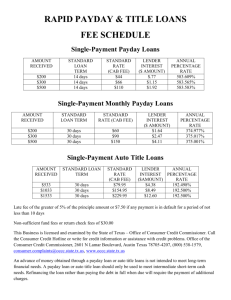

advertisement