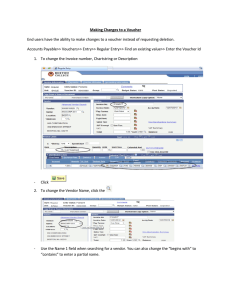

H P L I

advertisement