Using Public Schools as Community- Development Tools: Strategies for

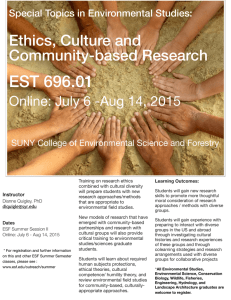

advertisement