Demystifying Outcome Measurement in Community Development

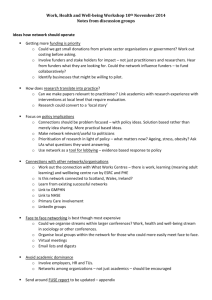

advertisement