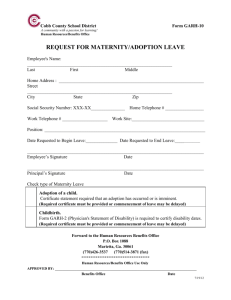

PRELIMINARY DRAFT COMPENSATING FOR BIRTH AND ADOPTION

advertisement