Griffin 1 By Austin James Griffin

advertisement

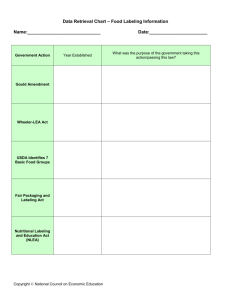

Griffin 1 Bigfoot[print]: Can Carbon Footprint Labeling for Food Products Work in the United States? By Austin James Griffin Sustainable Corporations, Spring 2015 Abstract This paper is meant both to provide an overview of carbon footprint labeling in the food industry and to consider labeling as a way to bring consumers into the sustainable corporation conversation. Since the conceptualization of the carbon footprint as a consumer tool in 2006, several companies have attempted to utilize it to further consumer understanding of products. These early attempts met several difficulties in complex methodologies, self-reporting integrity, and industry disinterest, but most of these issues have been solved since then through research and shifts in industry practice. The results of these solutions culminate in a new plan for product-level carbon footprint (PCF) labeling – convince five of the largest food companies in the United States to create a uniform PCF labeling system that will shift consumers, and the American food economy as a whole, towards low-carbon emission products, thereby placing the consumer in a more active role in the new sustainable economy. In the absence of this plan, the paper also makes mention of an alternative, the low carbon diet, that has already begun to take shape in Europe and the United States. Griffin 2 Bigfoot[print]: Can Carbon Footprint Labeling for Food Products Work in the United States? Introduction “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.” - Adam Smith The plans laid out by the architects of the sustainable economy are vast and varied - from renewable energy initiatives to closed-loop manufacturing. However, a gaping hole reveals itself in the consumer portion of the economy, particularly in food processing. Even Ceres, a leader in sustainable planning, fails to seriously consider the consumer side of its far-reaching ideals, devoting a single note to the PepsiCo-Walkers carbon label in its 2010 Roadmap for Sustainability. There is, however, a hopeful plan to engage the consumer in sustainable economics. This plan can be carried out in the food processing sector with the use of carbon footprint labels by five of the largest food production companies in the United States. In doing so, the market should react and provide consumers with carbon labeled products to further the positive, informed consumption side of a low-carbon economy. This paper is separated into four parts: an overview of the carbon footprint labeling phenomenon, a series of case studies and results from previous attempts at labeling in the food industry, a proposed plan to footprint label products from five major U.S. food processing companies, and finally, a mention of an alternative system to labeling – the low carbon diet. To begin, the carbon footprint must be defined. The Carbon Footprint Defined The carbon footprint is the measurement of “the total greenhouse gas emissions caused directly and indirectly by a person, organization, event or product.” The focus of this measurement is an accurate and total accounting of greenhouse gas emissions that would otherwise add to the global emission rate, whether directly through activities like fuel combustion or indirectly through results like deforestation. The term “carbon” in “carbon footprint” actually refers to CO2e or carbon dioxide equivalent, the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) that it would take to have the same effect as a ton of the relevant greenhouse gas. The most common gases included under this CO2e system are “CO2 (carbon dioxide), CH4 (methane), SF6 (sulfur hexafluoride), N2O (nitrous oxide), NF3 (nitrogen triflouride), PFCs (perfluorocarbons), HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons) and CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons).” The footprint does not limit the measurement to carbon dioxide. Griffin 3 Figure 1: Measuring the Carbon Footprint via The Carbon Trust. The carbon footprint comes in several varieties, but the type most common to labeling regimes is the product-level carbon footprint (“PCF”). As seen above in Figure 1, this type measures “emissions over the whole life of a product or service, from the extraction of raw materials and manufacturing right through to its use and final reuse, recycling or disposal.” In considering the product life cycle, the PCF establishes a “link between climate change and individual goods and services, their manufacture and consumption.” This measurement in label format was conceived by an international, independent organization from London, UK known as the Carbon Trust. The Carbon Trust was founded in 2001 in part by the British government to serve as an expert organization for carbon emission measurement and sustainable planning. Since its beginning, the Trust has worked with several global clients such as GE and Coca-Cola to reduce their “environmental impacts.” However, their breakthrough in carbon labeling did not occur until 2006 with the “foot” label [see Figure 2 below]. Figure 2: International Carbon Labeling Examples, via http://www.pef-world-forum.org/. Since the creation of the “foot” label by the Carbon Trust, several international governments have also created their own low-carbon indication systems, also present in the Figure above. And, in addition to the Carbon Trust, other third party foundations for international carbon labeling schemes such as the PEF World Forum have stepped in in recent years to fill in the market options for both companies and governments. However, the growth in PCF labeling on an application level has not been as steady. Griffin 4 Previous Attempts at Carbon Footprint Labeling Since the carbon footprint label’s inception in 2006, several countries and companies have attempted to capitalize on its use to consumers. The results of these PCF labeling attempts have been mixed and four examples are provided below. 1. Tesco Supermarkets Tesco PLC, the largest supermarket chain in Britain, was an early adopter in PCF label use. It partnered with the Carbon Trust in 2007 to “put new labels on every one of [its] 70,000 products” to allow consumers to “compare carbon costs in the same way they [could] compare . . . calorie counts.” With a flurry of fanfare, Tesco began just that. However, by 2012, Tesco abandoned the project, citing frustration from the measuring process, which could take several months of research per product, and lack of support or interest from other similar companies. Helen Fleming, climate change director for Tesco, stated that the company had “expected that other retailers would move quickly to do it as well, giving it critical mass, but that hasn't happened.” Their enthusiasm was likely tempered by Tesco’s rate of research that only provided carbon footprints to 125 products a year. At that rate, the newspaper The Guardian found, Tesco would be researching carbon footprints for centuries to meet its 70,000-product goal. No other grocery store chain like Tesco has attempted this sort of PCF labeling scheme since then. 2. PepsiCo and Walkers Crisps One of the largest, most-well known food manufacturing companies in the world, PepsiCo also had a brief foray into PCF labeling with its Walkers Crisps. In 2007, Walkers Cheese & Onion crisps (potato chips) became the first product to carry a Carbon Trust PCF label [see Figure 3 below]. Through the Trust, PepsiCo mapped out the entire lifecycle of its Walkers Crisps, breaking emissions into four categories: raw materials, manufacture, distribution, and disposal. By doing so, and recognizing the “hot spots” in the product lifecycle, PepsiCo was able to reduce “the carbon footprint of Walkers Crisps 7 percent from 2007 to 2009, saving about 4,800 tons of emissions.” After Tesco’s decision to drop its PCF labeling scheme in 2012, PepsiCo echoed similar concerns about industry apathy in the Ecologist: “‘Although we've not seen the take up we'd have liked across industry, we still support carbon labeling as a way of helping consumers and business to understand and reduce their carbon emissions,’ [said] Martyn Seal, director for sustainability in Europe at PepsiCo.” Figure 3: Walkers PCF Label via Marketing Magazine. Griffin 5 Moving forward three years, the Walkers carbon footprint label could not be located on recent bags of crisps.1 Even the Carbon Trust does not list its actions with PepsiCo under client case studies on its website nor does Walkers Crisps reference a carbon label on their website. It is unclear what happened to this labeling scheme, although PepsiCo has spent time developing new software to calculate PCFs with Columbia University’s Lenfest Center for Sustainable Energy, among other sustainable initiatives. The results of this work have yet to be seen on the shelves. 3. Wal-Mart USA On July 16th, 2009, Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, announced a plan to create a sustainability index for its products, requiring suppliers to provide information that would eventually translate to a global supplier database of sustainability information and a sustainability index on a product’s price tag. The index is based on a 15-question survey that includes questions such as “Do you know the location of 100% of the facilities that produce your product(s)?” and “If measured, please report total amount of solid waste generated from the facilities that produce your product(s) for Wal-Mart Inc. for the most recent year measured.” Only four of the fifteen questions relate specifically to climate and carbon emissions, unlike a carbon footprint assessment. However, despite the apparent simplicity of this system, Wal-Mart’s plans for a sustainability index are still on track in 2015. By 2014, Wal-Mart “will have invited approximately 6,000 suppliers, who represent approximately 60% of [its] sales, to participate in the Sustainability Index.” For the year 2015, the company has opened another survey period to invite new suppliers and reevaluate those already participating. With all of this movement, however, there does not seem to be any new information on product labeling or PCFs available for consumer decision-making at this time. It may be years before Wal-Mart’s thousands of separate producers report enough information in the proper form to allow for labeling. 4. Max Burgers Beginning in May 2008, the Swedish restaurant chain Max Burgers has labeled its entire menu with PCF labeling [see Figure 4, right], providing a clearer picture of climate impact and “allowing and empowering [Max’s] guests to take the climate impact in consideration in their order.” Figure 4: Max Burgers PCF Menu Examples via Max Burgers These labels were the results of life cycle footprint research in 2007 similar to the Carbon Trust programs as well as national interest (the Swedish government has other low-carbon diet 1 This statement is the result of fieldwork in Sheffield, UK. The volunteer was unable to find PCF labels on any Walkers bags in the grocery on March 26th, 2015. Griffin 6 initiatives and its own climate certification program, Klimatmärkning). The labels have also continued to the present, unlike the other examples mentioned here. This continuation is likely due to the national interest Sweden has in climate change as well as Max Burger’s relatively small size as a family-operated business, which gives it more flexibility to make large changes and adhere to a strict series of environmental promises. Such promises garnered multiple awards, as can be seen in Max Burger’s 2011 Annual Report. These actions have worked on a consumer choice level, too. The company’s 2011 Annual Report boasts “sales of climate-friendly products have increased by 28% since we introduced climate labeling in 2008.” Note, too, that these sale numbers reflect larger sales of non-beef foods, such as salmon and falafel burgers – unexpected for Sweden’s first and oldest homegrown burger chain. Despite this increase in non-beef foods, though, the company claims “sustainability has proven to be one of Max’s most profitable initiatives ever. It has, in fact, proven to be more profitable than opening up new restaurants.” Although questions of consumer interest in the United States may temper these results, Max Burgers’ success gives credence to PCF labels for intelligent consumer participation and demonstrates solutions to problems faced by retailers trying to track carbon emissions through a product’s life cycle. These solutions, and other decisions by Max Burgers, will help form the Big Five Plan to affect the American food market in a later portion of this paper. Problems Moving Forward And Their Solutions Looking at the previous attempts to create PCF label schemes, a few problems arise in the areas of measurement and marketing that must be dispensed with before the Big Five Plan can fulfill its value as a PCF-based consumption participation system. Under measurement, both what is being measured and who is measuring are issues to consider, while under marketing, the interest and understanding of consumers and the industry as a whole must be provided. Measurement Issues 1. The Measurement Process The complexity and expense of the life cycle analysis process, even through third party analytics, prevented companies like Tesco from continuing early PCF labeling schemes. Not only would there be added research costs for compiling data, but also for presenting this data, reforming the system for its analysis, and eventually communicating the information in a welldesigned label to the consumer, retailer, or both. Compared to the years when carbon labeling began, though, companies now may have an easier time providing this information and compiling it, due to both internal and external changes in how the companies and the world perceive important information. When Tesco began its foray into PCF labeling in 2007, it did not already have in place a system for measuring carbon emissions of the products it sold. However, since then, the company has created a baseline for carbon emissions reduction at year 2006/07 and has updated and tracked its carbon emissions each year, creating an organizational footprint. Many other food companies, such as PepsiCo and Dole, have done the same in recent years, creating systems Griffin 7 and baselines for carbon emissions reductions. Because of this shift across industries, carbon footprint measuring for a single product may be easier, naturally stemming from a larger system already in place with baseline data already compiled. Further, though, for companies new to PCF analysis, life cycle assessment of carbon emissions may be available on a ready-made, global scale ISO principles. Having begun in 1946 in London, UK, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is a global, non-governmental body that creates international commercial and industrial standards for everything from health to food to sustainable development. It is composed of 163 member nations, including within this membership the United States, Russia, China, India, and most of Europe. In 2006, ISO revised ISO 14040:2006: Principles and Framework for Life Cycle Assessment. This framework would allow companies who are otherwise unsure of carbon footprint analysis to purchase an internationally-recognized “kit” standard from ISO for about $124 U.S. Although there are still expenses in actual analysis and compilation of data, costs would be cut by not having to develop a brand new system. The previous concerns voiced by companies trying to analyze PCFs are likely not as robust as they were less than a decade ago due to shifts in industry practice and creation of globally-recognized standards for life cycle assessment that can be tapped for a more focused PCF study. 2. Self-Reporting Concerns Another issue related to measurement is the value of the data provided by companies – not only is there a plethora of “climate labeling” schemes and analysis groups to choose from, but a company may choose, as Max Burgers did, to create their own system for analyzing carbon emissions information and displaying it. This self-reporting decision may create questions of integrity in the reporting value of PCF labels on products. However, this issue may be easily solved with outside reporting standards. The most obvious choice of regulator would be the federal government, which has policed the claims on packaging for over a century. Since 1906, with the introduction of the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act, the federal government has been tasked to prevent food, cosmetic, or medication labeling that “is false or misleading in any particular.” When consumer products do not fall within the purview of the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), another group, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), takes hold of any practices deemed unfair or deceptive to consumers. Both the energy efficient consumer products and alternative fuel labeling schemes fall under the FTC’s control. Fact-specific product labels in the U.S. also have a “long history dating back to the 1960s” and today include everything from hazardous chemicals to cancer warnings. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has even already regulated a form of sustainability reporting on product packaging through its National Organic Program while the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has succeeded in providing specific consumer information on energy efficiency in its Energy Star certification label. It would seem, then, that the administrative branch of the federal government is poised to regulate any industry (or industries) that decides to provide PCF labels for consumer information. However, as Professors Mark Cohen and Michael Griffin 8 Vandenbergh state in their discussion paper, The Potential Role of Carbon Labeling in a Green Economy, the ability for a government agency to prove that PCF label is completely true or misleading may be non-existent. In paper, Professors Cohen and Vandenbergh find one vital difference between PCF and other labels like organic or energy efficiency certification: the availability of the information being provided. Unlike organic practices or energy efficiency, that can be clearly established by given guidelines (e.g., whether a certain fertilizer was used or the results of specific tests), PCFs are frequently based on multiple assumptions about consumer behavior. For instance, “a product might be manufactured at several different facilities, each using different energy sources and having different paths of shipment to their final destination. Thus, two identical products might have different manufacturing carbon footprints. At the other end of the life cycle, consumers differ in how they use and dispose of the product.” By the nature of measuring a carbon footprint, assumptions will likely be made that a government could not confirm without the Orwellian implications of life-long surveillance. An amount of trust in self-reporting may be required, although third parties might also provide guidance and technology to track products through their life cycles may later develop. These two issues, methodology and reporting, only cover the private side of PCF labeling. Another set of problems may be faced in the marketplace among consumers and fellow industry members. Marketing Issues 1. Consumer Understanding Months of work and hundreds of thousands of dollars put into PCF analysis and labeling regimes will become pointless without consumer understanding. As Cohen and Vandenbergh relay in their discussion paper on PCF labeling, much time and money has been devoted to researching “consumer responses to labels with the goal of designing meaningful communication vehicles that will not mislead and will provide actionable information.” The ideal consumer response to the PCF label would be the purchase of a less carbon-intensive product over a more carbon-intensive one. Two questions appear from this goal: (1) How can companies make sure consumers will perceive the purpose of the intended information? (2) Will consumers behave in the way companies want them to? The answer to the first question appears in the label itself. As with any graphic representation of information, the possibilities for design nearly endless. In a short survey of the Ecolabel Index website, 33 of the 458 labels listed were specifically the carbon footprint of an organization or product. Even the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has broken available environmental labels into three types in its ISO 14020 series. These tiers are: “Type I: . . . a multi-attribute label developed by a third party; Type II: . . . a single-attribute label developed by the producer; Type III: . . . an eco-label whose awarding is based on a full life-cycle assessment.” Griffin 9 With other possibilities for labeling not even in development yet, consumers may be inundated with “low carbon” labeling schemes that vary from one company to another, weakening informed decision-making. Therefore, it is necessary for consumer understanding that these labels, at least within industries or among similar products, ought to be standardized. Professor Mark Cohen, in another paper on carbon labeling titled The Role of Information Disclosure in Climate Mitigation Policy, provided what he believes are necessary criteria for effective PCF labels. Cohen utilized the research and design history behind warning labels to create his parameters, which included: (a) standardized vocabulary, format, and print size, (b) negative framing of information, (c) fewer than four or five pieces of information on the label, and (d) clear placement on packaging. All of these criteria are already applied in consumer product industries in one form or another, but “negative framing” may be particularly difficult for some companies or industries selling consumer goods because it would require these groups to state that a product would have a negative effect on the earth by its consumption. However, “studies suggest that the negative framing may be more effective when households have only a modest interest in the environment.” The application of this criteria will likely stem from competitive confidence instead of interest in a consumer’s wellbeing. Application of these design standards, or standards like them, could provide clarity for consumer understanding in the marketplace. With a clear marketplace, a second question appears: will consumers care? In recent years, multiple studies have sought to find how consumers might respond to a PCF labeling scheme, and the results were fairly consistent and positive for labeling. For instance, in a 2012 economic study by a coalition of the USDA and Vanderbilt University, Carbon Labeling for Consumer Goods, the researchers found that, while meat and alcohol carbon labeling would “yield the highest reduction in total emissions,” consumers will likely react better where foods are more specifically labeled (e.g., “cod” instead of “fish”) and where consumers have more clearly low-carbon options. The study concluded “where consumers have a low carbon substitute, an inaccurate belief about the carbon footprint of the good, and where high carbon goods have a large market share . . . large reductions in carbon from being labeled” will result. It should be noted that this “inaccurate belief” about carbon meant that the consumers believed that $1 of price was equivalent to .48 kg of carbon emissions, regardless of the type of product, or that carbon emissions and price were positively correlated. This conclusion was also found in a 2011 Australian study that actually applied labels to consumer goods in grocery stores. In Consumer response to carbon labeling of groceries, a study done by Southern Cross University, researchers found that consumers again responded to carbon labeling when it correlated with price. Their methodology utilized a three-color system of carbon labels, similar to the “stop light” pattern [see Figure 5, right] and was applied in a neighborhood grocery store in suburban New South Wales, Australia over a period of two months, tracking sales and Figure 5: PCF "Stoplight" Labeling via Southern Cross Univ. Griffin 10 customer interest in the labels and products. Overall, the researchers found that, in labeling the thirty-seven products over a period of two months, green-labeled (lower carbon) product sales increased from 53% of purchases before labeling to 57% of purchases, and blacklabeled (higher carbon) product sales decreased from 32% before labeling to 26% of total purchases. The most obvious change, however, was in products where price and carbon emissions were positively correlated. As can be seen in Figure 6, right, when price and carbon signal were consistent, sales of green-labeled Figure 6: Labeling Results via Southern Cross Univ. products jumped from a little over 50% of sales to approximately 62% of sales. Further, sales of black-labeled products dropped significantly, from over 30% of sales pre-labeling to only about 10% of total product sales. Overall, these studies demonstrate that consumers will likely react positively to PCF labeling schemes, but will be more conducive to a label that correlates positively with the price of a product. If this label is also designed with clarity and standardization in mind, consumer understanding and interest should follow. However, even if consumers follow through with their interest, the best results will arise from industry reciprocation of this program. 2. Industry Interest (Reciprocation) Cited by Tesco and PepsiCo as a major reason for abandoning labeling efforts (see Previous Attempts at Carbon Labeling), lack of widespread industry acceptance may create the largest problems for companies wanting to start a PCF labeling scheme for their products. However, this fear may be unfounded. As already mentioned, many companies are now analyzing their carbon footprints and the life cycle of their products as a matter of course, reporting this information on their websites or through company corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports. Combined with the recent data on consumer interest in carbon labeling and the growth of clear standards for labeling and life cycle assessment through ISO, few barriers exist for an industry to begin a set of standardized, voluntary PCF labels for their products. The more homogenous and widespread an industry, the better chance it will likely have for PCF labeling. Further, all that is necessary for industry interest may be the decision of one large company to officially PCF label its products. This was the position behind Wal-Mart’s decision to begin its Sustainability Index scheme. As then-CEO Mike Duke commented, “[i]t will have a ripple effect [because when] the big guy on the block does this, it makes everyone else nervous." This is also the position behind the “Big Five” Plan for PCF labeling considered in the next section. Griffin 11 The “Big Five” Plan Having considered previous attempts at PCF labeling for consumers and the problems and solutions that may arise in a new PCF label scheme, this paper reaches its apex: a new plan for carbon labeling in the United States. This new plan is simple in its structure: convince five of the largest food processing companies in the United States to start PCF labeling their food products as part of packaging to inform consumers. The five players in this plan are Dole, PepsiCo, Kraft-Heinz, General Mills, and Nestlé. They were chosen because they are some of the largest food production companies in the world, not only the United States, they have clear brand recognition, and they represent over $93 billion in combined food sales from 2013 in North America alone. For comparison, the entire snack foods market in the United States for 2015 is expected to be worth only $47.5 billion. Their associated brands are nearly ubiquitous as well, controlling varied food products from candy to yogurt to frozen pizzas. These companies combined also easily work against the problems faced by previous PCF labeling attempts. In response to measurement process and self-reporting concerns, each of these companies already use life cycle assessment or organizational carbon footprint analysis as a matter of course for their sustainability reporting2 and, unlike the retailers mentioned in the previous sections, these companies have clearer access to supply chains for more accurate PCF analysis because they produce these products. Also, although some of these companies have created in-house carbon emissions tracking and reporting guidelines, others, such as the global behemoth Nestlé, have chosen to apply the ISO 14000 standards for environmental reporting. Use of these ISO standards, or more uniform industry standards with a possible third-party verifier will help provide a more solid foundation for self-reporting amongst these companies as well as providing a competitive atmosphere among brands. The concerns regarding consumer understanding and industry interest could also be attended to in this labeling plan. As already mentioned, consumers will chose low-carbon products more frequently if they have options amongst products and the labels are clear and uniform within product categories. With five of the largest food production companies working together to produce a uniform label format, the shelves of any grocery or convenience store in the United States will contain carbon-labeled products for consumers to compare and purchase. As for industry reciprocation, the benefit of having the largest companies act will hopefully create a “ripple” effect as mentioned previously. Even other industries, such as retail and vending, will be affected by this ripple- the products they sell will arrive already labeled. By merely stocking Nestlé, PepsiCo, or other brands, the local grocery or gas station will be encouraging consumers to consider the carbon emissions of their favorite brands without having to do any complete life cycle assessment. This Big Five Plan, if adopted, should be able to meet each of the issues presented for PCF labeling and allow for the consumer to take an active role in creating a low-carbon 2 See linked sustainability reports and measures for each company: (1) Nestlé; (2) Heinz; (3) Kraft; (4) Dole; (5) General Mills; and (6) PepsiCo. Griffin 12 economy. However, if the companies choose not to act, there are alternatives for consumer action that have been considered by governments and researchers alike. Alternatives to PCF Labeling: A Low-Carbon Diet Considering the scale of the aforementioned “Big Five” plan compared to previous, unsuccessful plans, and the problems faced by both, other alternatives should be also considered for consumer participation in a low-carbon food system. This section highlights one of the most likely options: the low-carbon diet plan. Globally, the food production system accounts for at least one third of all annual greenhouse gas emissions, according to a 2012 report by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Other groups count the global food production system to include over half of annual emissions. Further, this share may grow, as daily caloric intake per person globally is expected to increase through 2050, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). In seeing these trends, some governments and activists, such as Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, have offered the option of a national low-carbon diet policy – dietary guidelines that would focus on environmental as well as individual wellbeing. Figure 7: Diet Carbon Footprints via Shrink That Footprint. As seen in Figure 7, left, the low carbon diet would likely be low in meats such as beef and lamb, and higher in plant-based foods and sustainably raised fish. Although the United States government has not completed its new guidelines by the date of this paper, sustainable diet guidelines have been presented to the USDA for consideration in the new 2015 plan and previous low-carbon dietary guides have already been adopted by other governments such as Sweden and the Netherlands. Apart from governments, multiple organizations provide guides for individuals wanting to consume lower carbon foods. This alternative has its own drawbacks, however, because this information would have to be sought out by consumers, rather than being present on packaging. Yet, both the labeling scheme and dietary guidelines are based on certain expectations that consumers will want to act for their own wellbeing and that of the environment. In a country like the United States known for its fast food and generally unhealthy choices, this may be a pipe dream. With the advent of Generation Y, though, consumption patterns are changing towards generally sustainable products, according to organizations like the Pew Research Center and Yale. Griffin 13 Conclusion Since 2006, use of the carbon footprint label has grown globally, catching the attention of industries and consumer groups alike. Multiple companies have attempted to attach PCF labels to the products they create or sell in order to give consumers a chance to participate in the sustainable economy. Unfortunately, most of these attempts in the last decade have been disbanded due to problems such as industry interest and complex methodologies. However, recent changes in industry, consumer interest, and international standards have all but abrogated these problems with PCF labeling and a new plan for applying PCF labeling to the American market appears. Using five food-processing companies with recognizable brands and huge market presence, the PCF label may become a tool to involve consumers in sustainable decision-making, with entire industries informed by the products they purchase (or don’t). Even alternatives to this labeling scheme demonstrate the importance of consumer involvement. With the rise of Generation Y and other interested groups, the consumer will likely have a more active role in a new low-carbon economy than ever before, making the sole end of new production, to paraphrase Adam Smith, conscious consumption.